Bush: the London area origins of an Australian term

In 1974, soon after taking up a research post at the ANU in Canberra, I published a Note on the origin of the distinctive Australian term "bush". [It appeared in Australian Literary Studies, vi (1974), 431-4.] I challenged the conventional explanation that the word was imported from South Africa, pointing instead to a number of place names in the London area which suggested that it would have been familiar to many convicts as a descriptive term. I return to the Note half a century on to review and extend its arguments.

I begin with an abbreviated version of the 1974 version.

"Bush": a Possible English Dialect Origin for an Australian Term

According to Sidney J. Baker, the term "bush" arrived in Australia about 1800 "and by 1820 had more or less completely ousted the English 'woods' and 'forest'". R. Dawson in 1830 introduced his English readers to "the woods, or bush, as it is called here", while ten years earlier Charles Jeffreys had referred to "the Bush Rangers, a species of wandering brigands" in Van Diemen's Land. E. E. Morris adds an example of "bushranger" from an untraced Sydney newspaper dated as early as 1806.[1] Yet, despite the early arrival of the term "bush" in Australia, and the subsequent mystique which has surrounded bush themes in Australian literature, there has been little consideration of the origin of the term.

G. H. Wathen, in 1855, quoting from a Westernport settler's letter written in 1850, explained: "The word itself has been borrowed from the Cape, and is of Dutch origin."[2] This explanation, that "bush" came from the Dutch "bosch" through the Cape Boers, has been put forward as the probable explanation in successive editions of the Oxford English Dictionary, and has been accepted, with varying degrees of caution, by standard authorities both in Australia and Britain.[3] Yet there are several problems about the explanation. The major one is to account for the transfer of the term from South Africa to Australia. It is true that the Australian colonies depended heavily on the Cape in their early years, and that most ships bound for New South Wales would touch there. But maritime and commercial contact encourages the transfer of maritime and commercial vocabulary, rather than that of a word descriptive of the interior. Furthermore, it may be assumed that convicts played a large share in the formation of early Australian vocabulary, and for obvious reasons it may be doubted whether many of them were allowed ashore at Cape Town. Nor is it likely that there could have been any sizeable interchange of English[-speaking] colonists between South Africa and Australia in the early period who might have acted as intermediaries. The British occupied the Cape in 1795 and again in 1806, and acquired it formally from the Netherlands in 1815. No important British settlement took place until 1820, when "bush" was apparently well established in Australian speech. In fact, it is unlikely that any large exchange of colonists took place between South Africa and Australia until the gold rushes of the second half of the nineteenth century.

Another problem in the theory of South African origin is the divergence of compound forms. "Bushman" in South Africa has a precise reference to members of the San tribe, but in Australia was applied to anyone skilled at living off the country, particularly Europeans. Similarly the South African term "bush baby" might reasonably have been expected, in a straight loan situation, to have been applied to small Australian animals. Perhaps least explicable of all are the references in the Oxford English Dictionary, which indicate the use of the term in the United States in the 1820s and Canada at a later date.[4] It is unlikely that it had spread from South Africa or Australia, and Dutch influence in North America had never been strong.

A more plausible explanation is the one which Morris quotes from an undated extract from the Sydney Morning Herald in 1894, which argued that "Canada, the Cape and Australia have preserved the old significance of Bush" as a traditional English term meaning "a territory on which there are trees. . ."[5] It would seem logical to seek an explanation in an origin common to all these countries. This Note attempts to establish the currency of "bush" in the place names of one English county: Essex. It argues that the term was probably understood, at the period of the foundation of Australia, to refer to woodland, or uncleared ground somewhere between open heath and dense forest. Sources are the accurate county atlas published by John Chapman and Peter André in 1777, and P. H. Reaney's The Place-Names of Essex (English Place Name Society volume xii, Cambridge 1935).[6] These sources give 33 place names including the element "bush". [The point of a research Note was of course to list these examples. For the 2023 revision, I have shifted them to an Endnote.[7] My updated argument concentrates on the importance of two examples, Harlow Bush Common and Hawkesbury Bush.]

[The 1974 text continues:] It seems reasonable to argue that "bush" in these names not only referred to stretches of woodland but was probably still understood in that sense by local people at the end of the eighteenth century. Many of the names specifically referred to woodland, and examples are commonest in the south-west and centre of Essex where forest cover is still extensive after centuries of clearance. Names like Shrubush, Oaks in Bush and – possibly – Bush Elms, would suggest that the term did not indicate a single bush – itself an unlikely basis for the formation of an identifiable place name – but rather a stretch of country. It is also likely that the evidence would be clearer but for the efforts of outside mapmakers and clerks to make sense of a term they did not understand by converting it to the plural. Although this survey is confined in detail to Essex, there are similar examples in adjoining counties: in Middlesex, Shepherds Bush is an obvious example, and can be traced in wholly singular forms in the seventeenth and eighteenth century.[8] Hertfordshire also yields a number of examples.[9] Between 1788 and 1819 one third of the convicts transported to Australia came from London,[10] and the rapid growth of London in that period certainly involved migration from the surrounding country. It is thus likely that a number of convicts were either country-born or familiar with rural dialect terms. To these it would have been natural to refer to Australian woodland as "bush". Other early convicts and settlers, to whom it would be a strange term, might have adopted it precisely because it expressed the alien nature of the Australian countryside. Far from borrowing the Dutch "bosch" they were probably reverting to a meaning common to both words.

Afterthoughts, 2023 Half a century later, it is – I hope – possible to look again at my own work with critical detachment, having reached an age where I no longer feel the need to contest every inch of ground in the trench warfare of academic controversy. In fact, there is no need to defend each and every argument advanced in the 1974 Note, since – so far as I can trace – nobody has ever referred to my theory that the Australian term "bush" was originally an English dialect term.[11] Perhaps my offering was so absurd that it has been politely ignored. But it may be that the wave of Australian nationalism associated with the Whitlam Labor government meant that I had not chosen the ideal moment to propose an English origin for an iconic term.[12] The 1972 general election had seemed to herald a new era in the way Australians understood their country. Two years earlier still, the academic consensus had been challenged by the New Left revisionism of Humphrey McQueen's A New Britannia, which sought – as usage now dictates – to decolonise the country's radical tradition, notably by confronting its essential racism.[13] Few academics supported McQueen's wish to redefine the Australian proletariat as a step towards a Communist revolution – Paris 1968 had been a little slow to reach Australia – but it was hardly the moment to suggest that the bush, a major defining theme in the national experience, was a derivative term. Of course, it may simply be that research notes in academic journals generate very few readers and even less impact.

Reviewing the note dispassionately, as I might assess the work of another, I have to say that it still seems persuasive, although this is not deny that it can benefit from scrutiny and some modification. No doubt it demonstrates new-chum weaknesses in its failure to capture nuances of value and meaning in the bush ethos. Inadvertently, I conveyed the impression that the term "bushranger" arose around 1820, when in fact it was not only current in New South Wales by 1806 but – as further discussed below – it was also responsible, in this compound form, for intruding the new meaning of the term "bush" into official despatches and reports. While I still contend that I was right to question the alleged transmission of a South African Dutch term into what was probably convict speech, I did not submit my own hypothesis to similar questioning, to ask how a dialect term from the area around London could have been adopted and adapted as a description of Australian landscape. My argument was also open to the objection, had anyone bothered to engage with it, that I had confused, or at the very least telescoped, dialect with toponymy. Place name elements may be deeply embedded in a regional culture, but this does not prove that descriptive terms used by Anglo-Saxon settlers were still comprehended hundreds of years later.[14] It is undoubtedly a weakness in my theory that neither the English Dialect Dictionary, published between 1898 and 1905, nor E.F. Gepp's Essex Dialect Dictionary of 1923 contained entries for "bush" in any sense comparable to its Australian meaning.[15] Indeed, it was probably a tactical mistake to concentrate so heavily on examples from my native county of Essex, merely mentioning those from the adjoining East Saxon areas of Middlesex and Hertfordshire. Hence, in this reconsideration, I focus on four widely known place names in the London area that might reasonably be assumed to have left a mark on convict speech.

"Bush": dating the term Before speculating on the origin or evolution of the term, it is necessary to trace its first appearance in New South Wales speech. Baker noted an example in 1803 and deduced that "it arrived in Australia at the beginning of the last century [i.e. c. 1800]". However, he also noted "bush native" (for an Aboriginal person) in 1801, the compound form suggesting that it was already in circulation. In proposing to push Baker's origin dating back by at least two years, I should offer a comment on the available sources for the founding decade of the colony. As might be expected, they fall into three groups: memoirs, mostly based on the diaries of officers, documents, in the form of two impressive multi-volume series of published source materials, and the press. However, in relation to the early history of Australia, they function in an unusual combination.

The remarkable and bizarre experiment of the establishment of a colony of thieves on the far side of the globe spurred a number of First Fleet officers to compile accounts of the early years of the settlement, some of which were published in response to apparent public interest. The surgeon George Worgan described the countryside around Sydney Cove as "a great Extent of Park-like Country, and the Trees of a moderate Size & at a moderate distance from each other". (The ecological term for such a landscape is "savannah": it does not occur naturally in Britain or Ireland.) Since the tree cover was not thick enough to be termed "forest", the friendlier term "woods" seemed the closest English equivalent. Worgan noted that the first Aboriginal people "scampered into the woods" as the convict transports sailed into Botany Bay. Later, he complained that convicts preferred to "skulk about the woods" rather than work.[16] Governor Phillip similarly reported that an attempted escape by a prisoner in June 1788: "He had hoped to subsist in the woods, but found it impossible."[17] These officer-diarists formed an impenetrable wall against convict speech: one of the most intelligent of them, Watkin Tench, regarded the thieves' dialect as at least a symptom and probably even a cause of criminality: "indulgence in this infatuating cant, is more deeply associated with depravity, and continuance in vice, than is generally supposed."[18] Such narratives became fewer after 1793, when the alternative news agenda of war with France captured a British public that was perhaps tired of the novelties of Botany Bay. Hence there were few opportunities to note the emergence of a new colonial vocabulary. Such slight evidence as survives from the first years of settlement indicates that the convicts also used "woods" before the evolution of "bush".[19]

In regard to documentary sources, historians of early Australia might seem to have access to an embarrassment of riches. In 1892 – it was a by-product of the celebration of the centenary of European settlement four years earlier – the first volume of the Historical Records of New South Wales (HRNSW) was published. Ten years later, Volume 7 reached 1811, at which point the State government ran out of money. Another decade passed, and the Commonwealth Parliament not only took up the project, but started afresh from 1788 with the Historical Records of Australia (HRA). Even under the pressure of world war, HRA managed to produce eleven volumes in its first five years, taking the story to 1825. While HRA firmly concentrated on governors' despatches, HRNSW also reproduced unofficial correspondence, for instance from missionaries. However, its editors – especially the librarian F.M. Bladen who took the story forward from 1793 – were free in use of contemporary Australian speech in adding marginal headings and endnotes, with the result that index references to the term "bush" invariably refer to interpolations. Both series tended to ignore convict voices, which were generally only heard when transcripts of court proceedings were sent to London. Considered together, the two series constituted a remarkable achievement, especially in an era when Australia was generally regarded as deficient both in history and intellectual activity. Yet their downside was the sheer bulk of the volumes produced, averaging over 800 pages of close type: for a lexicographer searching for a single word, the terms "needle" and "haystack" come to mind. Indeed, internal referencing in Austral English, the first attempt at a survey of Australian usage, published in 1898, suggests that its author, E.E. Morris, had largely completed his research before he allowed HRNSW to make much impact upon him.[20] I claim no superior diligence, but I have benefited from online search facilities to identify instances of "bush".

The third source to which students of contemporary vocabulary would naturally turn, newspapers, simply did not exist in Australia before the founding of the Sydney Gazette in 1803. As its title indicates, it was intended to be a semi-official publication and it was subject to censorship. Hence the use of standard English was not simply a matter of editorial good manners, but a hegemonic device to remind convicts, ex-convicts and soldiers of their exclusion from the local power structure. The fact that the term "bush" intruded into its third issue suggests that the word was already in reasonably wide circulation. However, although this is the source of Baker's first attested example, it tells us little about the date of its coinage, and still less about the process of its evolution.

"Bush" as a term for the Australian environment seems to have been first recorded in August 1798. Three months earlier, a convict transport, the Barwell, had arrived at Sydney after an eventful voyage in which some of the guards had allegedly conspired with felons to seize the vessel and head for the French colony of Mauritius.[21] The ensuing court proceedings were complex, and doubt was cast upon the evidence of a recently arrived convict called John Broadbent. Two privates in the New South Wales Corps, John Brown and Thomas Turner, claimed that Broadbent had claimed ignorance of any shipboard plot, and that he regretted and resented being forced to give evidence in the case. The two soldiers testified that Broadbent had told them that "if he had known as much at that time as he did then he would have seen the Court damned before he would have gone near it, for that he would have gone in the bush".[22] The Barwell had dropped anchor on 18 May, and its inmates probably did not disembark at once. The conversation was said to have taken place around 10 August. If Brown and Turner had captured Broadbent's exact words, then the term "bush" must have been sufficiently entrenched in the local vocabulary to have been absorbed by a newcomer who had been in the colony for about three months.

Was the testimony of the two soldiers reliable? There were two privates in the New South Wales Corps called John Brown. Both had been in the colony for some years, but the witness here was almost certainly the marine who had arrived with the First Fleet and transferred to the Corps five years later. He had received a land grant at Prospect Hill in 1792 and, shortly after, joined with a small group of settlers around Parramatta in petitioning for a Catholic priest. He was running a bakery, where the encounter was said to have taken place and had in fact been granted his discharge from the Corps a few weeks before the court case, although it may not have become operative.[23] Thomas Turner had arrived in June 1797, and had therefore been in New South Wales for just over a year.[24] Since they used identical wording in court, it is more likely that the two soldiers had rehearsed their testimony to cast Broadbent's comment in a plausible form – evidence, therefore, that "bush" was a generally accepted term for districts beyond the settlements. However, giving evidence himself a few days earlier, Broadbent had been uncommunicative in answering questions. A fellow-accused, obviously briefed about the evidence the two soldiers would present, asked him if he remembered saying "that had you have known yesterday as much as you did to-day you would not have appeared at all, but would have run in the woods?" Broadbent's reply – " I do not recollect having said so" – was a repeated refrain, but perhaps he felt able in good conscience to deny having uttered those precise words.

Of course, F.M. Bladen's occasional editorial interpolations of the term "bush" might lead to suspicion of mistranscription, but its currency seems to be confirmed by the more austere text of HRA, which reported the trial in February 1799 of four men accused of breaking into a tobacco warehouse in Sydney. One witness, Richard Baylis, gave evidence that he had been asked to accompany a fellow convict called Samuel Wright: "they went into the Bush; and got one Basket of Tobacco which had been left concealed there".[25] (Blaming Samuel Wright was sound strategy, since he had been "lately executed for Burglary".) Where Broadbent had spoken of the bush as a remote place of refuge, Baylis was evidently describing an area very close to the main settlement. In October 1799, there followed a serious case in which detailed and serious evidence was heard over several days. Governor John Hunter was determined to crack down on frontier violence along the Hawkesbury River. Aboriginal people had retaliated for the murder of a woman and child by killing two Europeans. It was alleged that five settlers had then "barbarously" slaughtered two "native boys" who had spent much time among them and evidently trusted the newcomers.[26] The accused submitted a written defence, which referred to their "coming from the Bush" a fortnight before the murder of the settlers had been known. A convict called John Tarlington painted a picture of friendly inter-racial relations, describing a group of Aboriginal people in the garden of a farm where melons were grown: "the native Jemmy went some little distance from the Melon ground and shouting out something in the Native Dialect which the Witness did not understand about twenty or Thirty Natives thereupon immediately came out of the Bush; and saluted the witness friendly".[27] However, another settler, Isabella Ramsay – at whose farm the two young Aboriginal boys had apparently been shot by an impromptu firing squad – referred in her evidence to a European "lately killed by the Natives in the Woods", which would indicate that bush terminology was not yet in universal use.

A further, and notable, example was recorded in September 1800, when Samuel Marsden, the notorious flogging parson, was investigating conspiracies among Irish convicts transported for their part in the 1798 rebellions. One centre of disturbance was Toongabbie, near Parramatta at the head of Sydney Harbour. Marsden took an affidavit from a man called John Riordon (probably Riordan), who swore that another prisoner, Michael Quinlin (probably Quinlan) had "told him that he was to lead Fifty men from Toongabby into the Bush last night, to get the Pikes which were concealed there. That with this Body of men so armed, he was to attack the Soldiers when in Church at Parramatta – that at the time the Deponent received this information he agreed to accompany Quinlin into the Bush; and to assist in attacking the Soldiers in the church this day". Four other Irishmen "agreed to accompany the said Quinlin into the Bush" and take part in the attack. The plot was foiled because one of the principals – it is not clear whether Riordan or Quinlan – had "got drunk and been made a prisoner of before he again became sober".[28] I have not identified Quinlan, but Riordan had been convicted at Cork, and had reached the colony eight months earlier. Since there seems no reason to assume that Marsden would have put those words into the deponent's mouth, it should be noted that a recent arrival from Ireland had so easily adopted a local form of speech.[29]

It seems fair to assume that convicts, soldiers and small-scale settlers in outlying areas were similar in social background and educational attainment. The four examples quoted above demonstrate that "bush" was in use among them as a landscape term in the years immediately before 1800, slightly before Baker's estimate. As reviewed below, it was also beginning to establish a linguistic foothold among the colony's elite, but there can be little doubt that the transmission process was bottom-to-top. A word that can be demonstrated to have been in use by 1798, when the oldest children born in the colony were ten years old, was obviously the creation of the adult population who had come from Britain or Ireland.[30] Furthermore, the apparent resistance of the elite to adopt the term indicates that it evolved among the convicts and their guards.

With these points in mind, we may now turn to the often-quoted example that has been taken to date the term's emergence to 1803, the squib from a correspondent that appeared in the Sydney Gazette in April 1803. Commenting on an unidentified report that "an Academy for Tᴜᴍʙʟᴇʀs" was planned for The Rocks, an insalubrious waterside district of Sydney, the writer declared: "you might, with an equal promise of success, recommend some parts of the ʙᴜꜱʜ for an improvement in the talent of Dᴀɴᴄɪɴɢ, as there much instruction might be expected from the assistance of the accomplished Kᴀɴɢᴀʀᴏᴏ."[31] The small capitals conveyed sarcasm, combined with an element of disdain for the locally-evolved locational term: readers of the Sydney Gazette were expected to understand what it meant, but its ironic impropriety discredited the notion of any project associated with the town's slum district. Yet the acceptability of "bush" was evidently growing. In June 1804, the paper reported a conspiracy by "restless characters" at the outlying convict settlement of Newcastle: two ringleaders had "escaped into the bush". A month later came news of a tragedy at Prospect, a farming settlement of ex-convicts thirty kilometres inland. On discovering that a two-year old boy had gone missing, his mother "rushed into the bush attended by several friends and neighbours", but found his body half-devoured by native dogs five kilometres away. There were two further examples of the term before the end of 1804, all of them used without any implication of editorial distaste.[32]

There are signs, too, that this upstart colonial word was starting to permeate the upper ranks of colonial society. A recent biography of Samuel Marsden states that he had transformed a land grant at Parramatta into "Bush Farm" before acquiring more additional holdings in January 1798. Certainly when the missionary Rowland Hassall arrived that year, Marsden arranged for him "to live at his farm, in the North Bush".[33] By 1805, an advertisement in the Sydney Gazette could refer to "Mr Laycock’s Farm on the Parramatta Road, commonly called Home Bush".[34] Thomas Laycock had arrived in the colony as a sergeant in the New South Wales Corps in 1789, and had risen to the rank of quartermaster. His role in the issuing of rations and stores kept him close to the soldiers. Marsden could hardly be described as a listening person, but his role both as clergyman and magistrate brought him into contact with convicts and soldiers, as his role in exposing the Toongabbie conspiracy indicated.[35] Where the officers and more senior administrators could remain aloof, neither Laycock nor Marsden could do his job without understanding the ordinary speech of the colony. Other recruits associated with the official class also slipped easily into the use of "bush" terminology. The botanist George Caley arrived in April 1800, keen to classify the species of eucalyptus trees. A young naval officer, James Grant spent less than eleven months in Australia, from December 1800 to November 1801, and was at sea for most of that time, exploring Bass Strait.[36] Both referred to Aboriginal people as "bush natives", Caley in a letter to Sir Joseph Banks in August 1801, Grant in his published account of his explorations the following year.[37]

In 1805, another recent arrival used an emerging compound form of the term, inadvertently revealing some complexity behind its coinage. When the merchant Walter Davidson had stepped ashore in June, he was welcomed by influential friends. Governor King had promptly granted him 2,000 acres (809 hectares) of land at Parramatta, where he assumed administrative responsibilities. Davidson encountered a floating frontier population, some of whom claimed that they had found a way across the Blue Mountains, which were a barrier to the advance of settlement. About four months after his arrival, Davidson sent "[s]ome men who had been in the practice of frequenting that part of the Mountains lying west of the Settlements at Hawkesbury" on a reconnaissance mission, to see if their reports might justify regular exploration. Not surprisingly, they returned with fantastic tales which failed to win his approval. "The whole of their Story is so contradictory that I should not have inserted these particulars but to prove what little Confidence can be put in this Class of what is locally termed Bush Rangers."[38] This was not the first example of a term that would acquire a particular resonance in Australian popular culture, but it is noteworthy in describing, at that time, men living on the margins of society rather than violent criminals. No doubt, the distinction was a fine one. Convicts who had escaped from the settled area – "runaways" or "bolters" – were offenders by definition, and their inability to live off the country soon turned them to theft. At about the time of Davidson's report, the Sydney Gazette twice referred to "the Bush Rangers" (a term that it had first published in February of that year), but these were but apparently runaways illegally employed by outlying Hawkesbury settlers and not necessarily criminals.[39] The transition from wanderer to bandit did not take long. In November 1805, the Sydney Gazette described the captured runaway John Winch as "a Bush Ranger and notorious character". Four months later, it reported the surrender of John Bellar "a bush-ranger who calls himself a Russian", a conceit that was not explained but perhaps suggests some form of mental illness. He was "brought before a Bench of Magistrates, and the offence of absconding from public labour being much aggravated by several charges of depredation, he was sentenced [to] 500 lashes." Bellar, then, was a bushranger because he had absconded. The pilfering necessary for survival merely added to the offence.[40]

In retrospect, it seems strange that it took the colony so long to evolve its own descriptor for runaway thieves. "There are at this time not less than thirty-eight convict men, who live in the woods by day, and at night enter the different farms and plunder for subsistence," wrote Watkin Tench in 1791. "… All the settlers complain sadly of being frequently robbed by the runaway convicts, who plunder them incessantly."[41] "We have now … a band or two of banditti, who have armed themselves and infest the country all round, committing robberies upon defenceless people," Governor Hunter reported to London in 1796. Hunter cursed them as "depredators" and a "set of plagues". [42] Three years later, he issued a proclamation denouncing as "worthless characters" "a number of the public labouring servants of the Crown [who] have very lately absconded from their duty … many of them said to have taken to the woods, and do of course mean to live by robbery".[43] It may be suspected from the combination of convoluted phraseology and common abuse that the colonial elite felt reluctant to dignify the marauders with a specific designation.[44] Similarly, a free settler, George Suttor, bemoaned attacks by attacks by "scoundrels" from the "woods".[45]

In 1804, new convict colonies were established in Van Diemen's Land (later Tasmania). Lessons had evidently not been learned from the challenges that had almost overwhelmed the founding of New South Wales. Within a year, the settlements faced starvation. As a desperate resort, convicts were issued with guns and dogs, and dispatched to hunt for kangaroo meat. Many chose to remain at large. Whereas the bushrangers of New South Wales were indigent stragglers on the margins of the community, in Van Diemen's Land, they were armed, confident and violent. In January 1806, the governor issued the first of a series of proclamations, urging eight named escapees to surrender. By August 1807, there were twenty-two convicts on the loose in the hinterland of Hobart and a further ten on the north coast. In the words of one historian, Tasmania was becoming a bandit society. The colony's resident chaplain, Robert Knopwood, was referring to "bush rangers". The term was acquiring far more sinister connotations, and in 1809 it broke through into the official record for the first time. Visiting Hobart from Sydney, Governor William Bligh reported to London that "it is a momentous concern that a Set of Free Booters (Bush Rangers as they are called) should be increasing in their numbers throughout the Country."[46] By about 1814, the terms "bush" and "bush rangers" were used without much comment both in official correspondence and newspaper reports overseas.[47]

This necessarily lengthy survey of the word's Australian origins may be simply summarised. "Bush" was in use as a locational and landscape term by 1798, five years earlier than the example from the Sydney Gazette usually quoted as it first appearance. This considerably reduces the time frame for its colonial evolution, for instance posing additional challenges for a South African explanation. The term was current among soldiers and convicts, but its use was resisted by the small literate elite of New South Wales. Around 1805, a compound term, "bush ranger", became current, with "bush" originally used adjectivally, then hyphenated and finally – by about 1820 – merged into a single word, an entirely new contribution to the English language.[48] On the Australian mainland, it initially referred to indigent itinerants who had fled the prison settlements, whose criminality was incidental to their survival. This may explain why the word formed around the term "rangers", which highlighted mobility, rather than some more condemnatory alternative such "bandits" – although it will be suggested below that there was a London-area echo in the choice. The rapid development of large-scale armed frontier warfare in Van Diemen's Land not only equated the new coinage with violent robbery, but also explained its adoption in official correspondence, if at first intermittently, from 1809. Yet it remains to explain, or speculate, how it evolved.

The South Africa theory "Recent, and probably a direct adoption of the Dutch bosch, in colonies originally Dutch," comments the Oxford English Dictionary on the etymology of "bush" as a term for landscape. By the late-nineteenth century, this was true of English-speaking South Africans, but it does not follow that the term was likely to have been borrowed by early Australian colonists from the Dutch burghers of Cape Town a century earlier. Influenced in particular by Geoffrey Blainey's illuminating Tyranny of Distance, I had acknowledged in 1974 "that the Australian colonies depended heavily on the Cape in their early years". However, precisely because New South Wales urgently needed South African supplies for its establishment and survival during its early years, there was pressure to make those visits as short as possible.[49] The First Fleet spent 31 days at anchor in Table Bay, a stopover which was unexpectedly prolonged by the reluctance of the Cape authorities to accede to Governor Phillip's demands in their entirety. "[S]uch officers as could be spared from the duty of the fleet" moved into boarding houses on shore and engaged in sight-seeing. However, their excursions were confined to the immediate area of the town, for "the country near the Cape had not charms enough to render it as pleasing as that which surrounds Rio de Janeiro", where the First Fleet had called three months earlier.[50] Even if the visitors had crossed the sandy Cape Flats, which constituted a barrier to access to the interior, they would have found nothing resembling Australian bush. The closest place-name examples, Rondebosch and Stellenbosch, were both situated in established farming country, where the land was described in 1778 as "uncommonly fertile, producing plenty of corn and wine, and all the fruits which are found at the Cape".[51] All travel into the interior of southern Africa was onerous and ponderous, making it virtually impossible for short-term visitors to learn about the hinterland, let alone pick up any local vocabulary relating to it.[52] In any case, the evidence indicates that "bush" emerged from the lower levels of New South Wales society, not from the top. Cape Town was equipped with a hospital for sick mariners, but no First Fleet sailors or marines were sent there, "a very rare circumstance at this place".[53] Sick convicts remained on their transports, since there was no question of allowing them ashore. The point was dramatically underlined when the Second Mate of the Friendship fell overboard in Table Bay. A prisoner who was a strong swimmer volunteered to dive to the rescue: he "had behaved with the strictest propriety during the voyage, and … there was no probability (if such had been the convict’s intention) to effect an escape". Nonetheless, permission was refused by the officer in command – he was a junior lieutenant, his seniors presumably having gone ashore – and the sailor was left to drown.[54]

In October 1788, as New South Wales ran dangerously short of food, Governor Phillip commissioned Captain John Hunter of the Sirius to return to Cape Town to purchase further supplies, including medicines that had been unaccountably overlooked in the preparations for the original voyage. In an impressive feat of navigation, Hunter sailed east, across the Pacific and round Cape Horn, a much longer route than the Indian Ocean, to take advantage of the prevailing winds in the deeper latitudes of the southern hemisphere.[55] At the Cape, "great surprise" was expressed at the ship's three-month, non-stop voyage, but it was achieved at a price: malnutrition and scurvy had left most if the crew unfit for duty. Forty sailors were sent to sick quarters on shore, probably at the town's hospital.[56] Since the Sirius was 61 days in Table Bay, this is probably the largest and longest stay in Cape Town by any group of men below officer rank. Yet it seems unlikely that they picked up much of the local language. Nor would there have been much opportunity for them to share their knowledge when they returned to Sydney. The available records naturally tell us of relations between convicts and marines, but there was much less contact with the sailors. Even when a ship was in port, there was plenty for the crew to do, and the personnel of the Sirius were based on an island in the harbour.[57] In March 1790, ten months after returning from the Cape, the Sirius was sent to Norfolk Island, where she was wrecked. The crew were saved, but remained on Norfolk Island until arrangements were made to return them to Britain in 1791.

The only large-scale landing of convicts in South Africa was the result of the wreck of the Guardian, a store ship which hit an iceberg about 2,000 kilometres east of the Cape in December 1789. Most of the ship's complement took to the boats, and only a few were ever seen again. Among those who remained aboard were 21 convicts, a specially selected group of skilled artificers in trades that were much needed in New South Wales. These men were, in effect, "trusty" prisoners who helped save the apparently stricken vessel, which eventually – after nearly two months – anchored at the Cape. Most of the stores destined for New South Wales had been jettisoned or were too spoiled for consumption, but the remaining cargo was transferred to warehouses while attempts were made to repair the ship. From the stressed and staccato reports of its commanding officer, it seems clear that the convicts (one of whom died at Cape Town) must have spent some time ashore, shifting stores and – after seven weeks – being transferred across the peninsula to False Bay, where they were loaded on to the Second Fleet, with recommendations for pardons.[58] Again, their scope for acquiring the local language would have been restricted and, as they would have constituted less than one percent of the population of New South Wales in 1792, their linguistic impact could hardly have been extensive. A convict who escaped from the Pitt in December 1791 was recaptured by the Dutch authorities and transferred to the next available transport in August 1792.[59] Other convict ships spent little time at the Cape: the Second Fleet needed only sixteen days in 1790, while the storeship Justinian bypassed the Cape altogether to achieve a fast passage from Britain that same year.

At this point, it should be acknowledged that early New South Wales did have one influential resident who had not only spent time at Cape Town but had travelled deep into the South African interior between 1777 and 1779. A Scot and an associate of Sir Joseph Banks, William Paterson was an officer in the New South Wales Corps with an interest in botany. He arrived in 1791, and spent seventeen months in command on Norfolk Island. Returning to the mainland, he led an expedition to the Blue Mountains in September 1793, and then served for nine months as administrator of the colony – without much distinction – before returning to Britain on sick leave in 1795.[60] Could he perhaps have imported the term "bush" and instilled its use into the men of the New South Wales Corps, thereby explaining its use by privates Brown and Turner in the August 1798 court case? However, his Narrative of four journeys into the interior of the Cape – its date of publication, 1789, suggests a promotional intention – twice mentions "bush Hottentots" (Khoikhoi), and occasionally translated the Dutch "bosch" as "wood".[61] There is little evidence that he regarded the South African interior as "bush" and none at all that he transferred the term to New South Wales. I can trace no further contact between the Cape and Australia among the official class until the transfer of Judge W.W. Burton to Sydney in 1832.[62]

The British occupied the Cape in September 1795, returned it to Dutch control in 1803, seized it again in 1806 and retained it in the peace treaties of 1815. Slow communications between the two continents hardly make it likely that the British occupation in 1795 could explain the use of "bush" in New South Wales three years later. In any case, John Barrow, the governor's intrepid private secretary, did not apply the term to his detailed descriptions of travels into the interior in 1797 and 1798.[63] As my Note stated, there was no substantial English-speaking settlement until 1820, when colonists were planted in the eastern Cape, about one thousand kilometres from Cape Town itself. There, in an area of relatively high rainfall, they encountered dense vegetation in what the Historical Geography of South Africa called "bush-choked valleys". Later in the century, as trekking Boers penetrated beyond the Orange River, South African English embraced the term "bushveld" for plateau country consisting of grassland dotted with clumps of trees and shrubs.[64] By the late-nineteenth century, a historian of South Africa could refer to the "growth of underwood peculiar to the country, known generally by colonists as 'bush'."[65] However, it did not follow that the term was current a century earlier and, even if it had been in use, it is almost impossible to see how it might have been transferred to Australia.

In dismissing the theory of a South African origin, it may be convenient at this point briefly to look at the incidence of the term "bush" in other English-speaking countries. In New Zealand, its use seems clearly to have derived from Australia and, in any case, sustained European contact began after the word had become entrenched in Australian speech. The first application that I have traced was in 1810, when the Scottish merchant Alexander Berry attempted to apprehend the Māori chief Te Pahi, who was wrongly believed by Europeans to have been responsible for the massacre of the crew of a whaling ship. (Berry had been sailing in Australian waters for two years: he seems to have imbibed colonial terminology without spending much time on land.[66]) Berry attempted to seize his prey at Whangaroa in the far north of the North Island, but was forced to report that "Tippahee has betaken to the bush and eluded my researches".[67] In New Zealand, "bush" came to refer to thick forest. In 1898, Morris quoted a Dunedin newspaper that seemed puzzled by the use of the word in New South Wales. "It is not the bush as known in New Zealand. It is rather a park-like expanse, where the trees stand widely apart, and where there is grass on the soil between them."[68] Although in recent times, the term has acquired a certain ecological mystique in New Zealand, "bush" never developed the romantic aura that gave it so central a place in Australian culture. This was partly because New Zealand was only indirectly and very marginally affected by convict transportation, but also because the bush was, by definition, impenetrable, hence few Europeans could survive there.[69]

"Bush" seems to have more tenuous connections with North America. The Oxford English Dictionary assumed that the term was current in eighteenth-century Virginia, but its evidence was a quotation from a short story of 1828 by Sir Walter Scott. This is hardly conclusive of American usage: Webster's Dictionary made no claim for the United States, explaining rather that this "original sense of the word" was "extensively used in the British colonies, especially at the Cape of Good Hope, and also in Australia and Canada".[70] In Canada, the term is forever associated with Roughing It in the Bush, a vivid account of the hardships endured by a genteel settler couple from Britain in the backwoods of Ontario. Published in 1852, Susanna Moodie's collection of sketches is regarded as one of the foundation and defining works of English-Canadian literature. However, its locational term is oddly unpersuasive, although it frequently appears – around one hundred times – in the text. Perhaps here there is the South African connection that so many reference works have fantasised about for Australia. Susanna's husband, J.W. Dunbar Moodie, had farmed for twelve years at the Cape, where he recalled living his life in "broken Dutch" for lack of English-speaking neighbours. Although he had wished to return, his bride's terror at the thought of elephants and lions had led the couple to emigrate to Canada, and they may have been influenced by his experience in their description of landscape. Susanna Moodie's London publisher apologetically explained to readers that the book had been seen through the production process without its author's involvement, and it may be that Roughing It in the Bush was chosen as a title without consulting her. In 1852, the British public's interest in Canada, which was never intense, was massively eclipsed by the excitement surrounding gold-rush Australia, and the publisher may have hoped to tap into the market for antipodean realism.[71] "Bush" does seem to have been used occasionally as a synonym for the Canadian backwoods[72], but the term was applied at a much later date for remote regions, for instance of northern Alberta and the Yukon. In Alaska it refers to any area off the road network, a classification that covers most of the State.

In summary, the rest of the English-speaking settler world can offer no help in explaining the emergence of the Australian term "bush" in the seventeen-nineties. It is time to revert to my 1974 hypothesis that we should seek its origin in Britain itself.

Bush: a London area origin? Fifty years on, I am happy to accept that the argument of my younger self was open to the same challenge that I deployed against the South Africa hypothesis: how was this term transmitted? Clearly, the eight convicts tried at Chelmsford – one percent of the original Botany Bay population – could hardly have imposed a local Essex landscape term upon a penal colony. Nor, indeed, did I make any such claim. Rather, my Note sought to establish that "bush" was in widespread use in Essex at a time when most common land had not yet been enclosed, indicating that the word would have been identified as descriptive of rough scrub used for communal grazing. Noting that it was also to be found in Middlesex and Hertfordshire, I suggested that it would have been a familiar term to convicts from the London area. I pointed out that, in the first third of a century of New South Wales, one-third of transported convicts came from the capital.[73] In fact, metropolitan dominance was even greater on the First Fleet. Of 778 transported felons, 279 had been convicted by courts in London or Middlesex. But London stretched south of the Thames into Surrey, notably in the crime hotspot of Southwark, and downriver to Deptford and Greenwich in Kent. I estimate that a further 36 First Fleeters were Londoners convicted in adjoining counties, bringing the total to 315 – and there may have been more.[74] Constituting around forty percent of the original unfree population of New South Wales, the London contingent was strongly placed to influence its forms of speech – all the more so because they had their own argot, a form of thieves' slang known as the "flash" language. Tench called its use "[a] leading distinction, which marked the convicts on their outset in the colony…. In some of our early courts of justice, an interpreter was frequently necessary to translate the deposition of the witness, and the defence of the prisoner."[75]

Baker resisted the notion that Australian English was a mere derivative of "flash", but he did accept that the lexicon compiled the convict James Hardy Vaux contained "sundry pointers as to the way our language was to go".[76] Vaux completed "A Vocabulary of the Flash Language" around 1812, and it was published aas an appendix to his memoirs seven years later.[77] Its racy content mostly failed to transfer to Australia and, indeed, very little of it survived in mainstream British-English either. Some of its terminology was inventive and amusing, such as "rumble-tumble" for a stage-coach, and "gully", a liar or fantasist, which drew on the literary inspiration of Gulliver's Travels. "Scottish", meaning "fiery, irritable, easily provoked", was a regrettable exercise in stereotyping, but perhaps comprehensible in eighteenth-century London. However, it is hard to understand why the Moon was known as "Oliver", or that "the country parts of England are called The Monkery". Not surprisingly, terms associated with city life permeated flash vocabulary. Thus "any scheme or project considered to be infallible, or any event which is deemed inevitably certain, is declared to be a Drummond, meaning, it is as sure as the credit of that respectable banking-house, Drummond and Co." By contrast, "anything paltry, or of a bad quality, is called a Leather-lane concern", taking its name from a cheap street market off Hatton Garden.

More remarkable were the examples that referred to places around London, some of them at some distance from the city. Vaux defined "come to the heath" as "a phrase signifying to pay or give money, and synonymous with Tipping, from which word it takes its rise, there being a place called Tiptree Heath, I believe, in the County of Essex." Few Londoners could have known Tiptree Heath, 800 hectares of common land located 90 kilometres from the city, away from highways and hence little known by travellers. The allusion here was presumably the result of word play. An unrelated phrase, "tip him the Dublin packet", referred to giving somebody the slip: probably it had been imported from some provincial port, such as Liverpool or Chester, which had passenger services to Ireland. Another mysterious word was "Tilbury", a synonym for a sixpence, for which Vaux offered no explanation.[78] Perhaps the most intriguing piece of London-area slang was "Staines", the name of a town 20 kilometres west of London: "a man who is in pecuniary distress is said to be at Staines". I return to that example below.

My collage of Essex place names was designed to build up an overall impression of the frequency with which the landscape element "bush" could be found. It was not intended to imply that, for instance, "Weekly Boush" at South Weald (now Wigley Bush) was a name that echoed along the pavements of the fashionable Strand or resounded in the crime-ridden alleys of Seven Dials. Hence, in this reconsideration, I propose to concentrate upon four locations with "bush"-related names that could reasonably have been expected to be known to late-eighteenth century Londoners, and to indicate how they may have influenced the development of the landscape term in Australia. They are Harlow Bush and Hawkesbury Bush in Essex, and Shepherds Bush and Bushy Park in Middlesex. In addition, an honorary mention might be made of the small Hertfordshire town of Bushey, and the nearby Bushey Heath, thirty kilometres north-west of London and located on the busy highway to Watford and the Midlands.

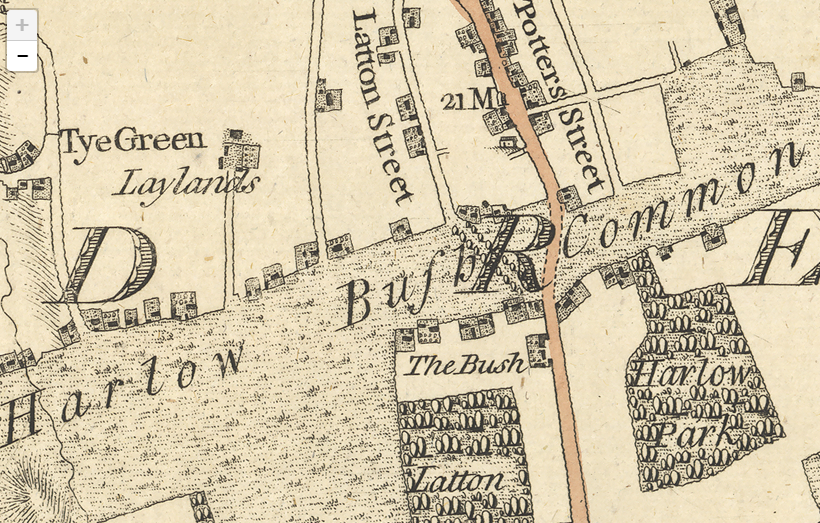

Harlow Bush Harlow Bush Common was a relatively narrow expanse of open land which stretched about four kilometres from west to east, in fact extending into the neighbouring parish of Latton, where it was called Latton Bush. Most of it seems to have been grass, but there was a patch of woodland to the south identified as Mark Bushes, the plural probably being an attempt by cartographers to make sense of a dialect term. On 9 and 10 September each year, Harlow Bush Common was the location of a massive commercial fair, which grew steadily more important throughout the eighteenth century. At Bush Fair, intending purchasers could inspect and maybe purchase "horses of all kinds for the waggon, the plough, and the saddle". It was also a major cattle fair, its importance obviously enhanced by proximity to the London market. In 1782, for instance, there was "the greatest number of Welch cattle at market at Harlow fair, that has been known for forty years".[79] Assembly rooms had been constructed in 1778 – originally in the form of a "tea booth" – which made the Fair a convenient opportunity for meetings: in 1785, for instance, an association of Essex innkeepers was formed for mutual protection against thefts.[80] Above all, Harlow Bush was a pleasure fair. By the time the cartoonist Thomas Rowlandson illustrated the scene in 1816, there were both permanent and temporary structures erected to provide entertainment for the crowds. The agricultural expert Arthur Young noted that "it affords a scene of no inconsiderable amusement, and its vicinity to the capital draws thither an amazing concourse of people, as well from thence as the neighbourhood in general, to an extent of fifteen or twenty miles around."[81] (London was just within Young's radius, about thirty kilometres away.) Naturally, the event attracted criminals, such as Catherine Wilmot, who was caught stealing two coats from a stall in 1786.[82] Harlow Bush Fair may be argued to have contributed to the collage of influences on early Australia English in two ways. First, its topography accustomed Londoners to the idea that the word "bush" denoted common land, covered with grass, scrub and trees, a notion that convicts would have taken with them to New South Wales. Second, "Bush Fair" came to signify a Saturnalia, an occasion when social norms were discarded, and people of all classes mingled without distinction of rank, an element captured in the Rowlandson cartoon. This may help to explain the Australian paradox, that the bush would be seen both as a place of hardship but also as a Utopia where structures of power and prestige were inverted or discarded altogether.[83]

Harlow Bush Common, in Chapman and André's atlas of Essex, 1777. The location of a popular annual fair, it would have accustomed Londoners to the notion that rough open ground was "bush".

Thomas Rowlandson's 1816 cartoon shows Harlow's Bush Fair in holiday mood – a place of escape.

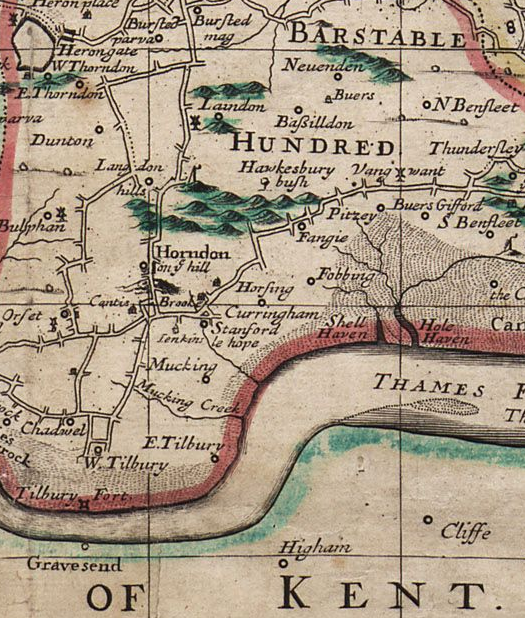

Hawkesbury Bush A "bush" place name in the Essex marshland parish of Fobbing might seem to refer to a backwater of purely local renown, a landscape feature that was unlikely to resonate on the other wide of the world. Six kilometres north of the Thames estuary, a sharp escarpment climbs to a knoll 70 metres above sea level – a prominent feature in an otherwise level landscape. This was crowned by a patch of mixed woodland and scrub which was marked on an Essex county map as Hawkesbury bush in 1678.[84] Its importance was explained by the Essex historian Philip Morant in 1768, with the bald statement in his entry on Fobbing: "Some trees here have been a Sea-mark, called Hawksbury-bush".[85] Below Tilbury, the Thames flows north through a seven-kilometre reach called the Lower Hope, before turning east into the estuary proper and the Nore. The narrow deep-water channel of the Lower Hope is aligned at a slight angle to an exact south-north line, meaning that a vessel sailing downstream would have needed to keep the horizon bump of Hawkesbury Bush on its left bow.[86] There can be little doubt that every sailor familiar with the Thames would have known the feature.

A sea-mark that guided Thames mariners, Hawkesbury bush was sufficiently important to feature on the single-sheet map of Essex published by Ogilby and Morgan in 1678.

In 1789, Phillip located a river which flowed into Broken Bay, about thirty kilometres north of Sydney. As Tench noted, "the river received the name of Hawkesbury, in honour of the noble lord who bears that title".[87] In an era when career advancement was lubricated by patronage, it made sense to flatter Charles Jenkinson, the influential trade minister in Pitt's cabinet. Three years earlier he had been elevated to the House of Lords with the title of Baron Hawkesbury, taken from a Cotswold village where he owned property.[88] Early in 1794, Phillip's successor, Major Francis Grose, began to settle ex-convicts on fertile land along the banks of the Hawkesbury. This initiative depended almost entirely on water transport from Sydney.[89] Fortunately, in a rare burst of initiative, the authorities in Britain had come up with a flat-pack solution to the colony's communications problem. In 1793, a convict transport had brought a kit of ship's timbers, which were assembled into the 41-ton schooner Francis.[90] Robust enough to cope with the open sea but small enough to sail a considerable distance up the Hawkesbury, the schooner was used to deliver supplies, including a small mill and arms and ammunition to the settler militia.[91] In April 1795, David Collins, one of the most observant of the officers, noted that "the colonial schooner returned from the Hawkesbury, bringing upwards of eleven hundred bushels of remarkably fine Indian corn from the store there".[92] This was a small but welcome step towards making the colony self-sufficient, and it depended upon an equally small but skilled complement of sailors.

The colony was fortunate in having an experienced mariner to act as master of its schooner. William House had been a bosun on HMS Discovery, part of Captain George Vancouver's expedition exploring the Pacific. Invalided and transferred to Sydney in April 1793, House was appointed as a Superintendent of Convicts and put in command of the Francis.[93] Discovery had been built at Rotherhithe and the Vancouver expedition sailed from the Thames. It is overwhelmingly likely that William House knew London's river, its hazards and its sea marks. I have found no information about the crew of the Francis, but they were probably ex-convicts, some with maritime experience and, as already noted, London-area felons formed the largest regional category on the early convict fleets. In the late eighteenth century, about three-fifths of Britain's overseas trade passed through the capital, and anyone with seagoing experience would have experienced the congestion and the dangers of the Thames.[94] It is possible to imagine the crew grimly joking about Hawkesbury Bush as the Francis picked its way cautiously along the narrow and tortuous course of the unknown river, selecting their own navigation marks to cope with hazards. William House might well have encouraged such banter as a way of building an esprit de corps among his men, or they might have used the term to express a sense of superiority over the ragtag of settlers who were attempting to carve out farms along the river. In fact, House was concerned at their over-enthusiasm in clearing the land, and by 1795 was making clear "his apprehensions that the navigation of the river would be obstructed by the settlers, who continued the practice of felling the trees and rolling them into the stream".[95] If the original Hawkesbury Bush had been buried among the glutinous byways of some inaccessible corner of Essex, known only to the handfuls of peasants, parsons and poachers who resided in that vicinity, we might dismiss its name as a pleasant coincidence, but one that was in no way connected to its antipodean namesake. But Hawkesbury Bush was identifiable with, and identifiable from, England's greatest commercial highway, a feature that would have been familiar to any Thames mariner. The chronology is suggestive too: the Francis probing the river in 1794-5, the term "bush" emerging into the records in 1798. There can be no doubt that the Hawkesbury settlements formed an important part of the original concept of the New South Wales bush, and the term was in use there by 1799. Of course, it may be impossible to prove that the Essex sea-mark provided the linguistic smoking gun that triggered the Australian usage of the term "bush", but it is highly likely that it contributed to its emergence.

Shepherds Bush The well-known inner London district takes its name from the V-shaped Shepherds Bush Green which remains an open space in 2023.[96] Popular etymology regards it as a spot where shepherds pastured their flocks on the way to market in London. This is charming but unlikely. Barely three hectares in size, Shepherds Bush would hardly have provided much feed for sheep and, flanked by two major roads, it would have been a difficult location to control such notoriously excitable animals. Recorded as Sheppards Bush Green in 1635, it is more likely to preserve a personal name, perhaps of a landowner or a nearby publican.[97] Located on the highway to Uxbridge and beyond, a few kilometres beyond London's expanding urban frontier, the area was still thinly inhabited in the late-eighteenth century and dangerous for travellers. A man was hanged at Newgate for robbery there in 1785; two weeks after the thief had dropped to his death in a spectacularly botched mass execution, a gentleman was relieved of his cash and his watch on the same stretch of highway. There were four more attacks between 1786 and 1790, the last of them a violent affray in which three footpads battered their victims with bludgeons. In addition, and in unexplained circumstances, Middlesex magistrates dispersed a "fighting mob" at Shepherds Bush in 1787.[98] At this point, the crime wave seems to have ebbed. Improved policing may partly explain the improvement: in 1792, the capital's embryonic detective force, the Bow Street Runners, was extended across the whole of Middlesex. But announcements of property auctions around Shepherds Bush in The Times suggest that the outer fringe of the urban frontier was on the march, reducing opportunities for surprise attacks: "The place termed Shepherd's Bush", a guidebook observed in 1815 "… has lately experienced a great accumulation of buildings."[99] Both through its location and its association with highway robbery, Shepherds Bush would certainly have been well known to the capital's criminal classes. Like the extensive common land at Harlow, although on a very much smaller scale, it would have conveyed the idea that a rough open space was "bush".

Given that "bush" emerged in demotic New South Wales speech at the same time as the foundations were laid for the pastoral industry, is it possible that there is a specific link here? Could it be that sheep runs were nicknamed Shepherds Bush, the term being quickly abbreviated to provide a generic term for the interior districts and landscape? This would certainly offer both an attractive etymology and a very neat and satisfying explanation. Unfortunately, the chronology seems to be against it. Sheep were still relatively unimportant in late seventeen-nineties New South Wales, while shepherds were few and operating mostly beyond the organised and populated settlements. At most, memories of Shepherds Bush may have reinforced the new meaning, but they could hardly have caused it.

"Sheep do not thrive in this country at present", Phillip reported to London in July 1788, when it hardly seemed likely that Australia was destined to rise to prosperity through the production of wool.[100] Most of the flock imported from the Cape was dead by the end of the year: some were killed by native dogs (or were perhaps clandestinely slaughtered by convicts) and, in a freak act of nature, some were struck by lightning.[101] New South Wales, it seemed, was simply not sheep country. Eight months after the arrival of the First Fleet, Phillip reported that just one of the seventy sheep he had purchased at Cape Town was still alive. He blamed "the rank grass under the trees" for killing them, adding that officers "who have only had one or two sheep which have fed about their tents have preserved them".[102] The lessons were obvious: if sheep were to be farmed in New South Wales, they would require not only the right pasture but also careful supervision to ensure that they grazed in safety. Neither was possible during the opening years of the colony.

The role of John Macarthur in the establishment of Australia's pastoral industry is well attested, not least because Macarthur was a ruthless self-publicist. He established a farm at Camden, sixty kilometres from Sydney, and well inland from the toxic coastal grass. In 1794, he purchased sixty sheep from Bengal, whose wool he described as "coarse hair". However, cross-bred with two ewes and a ram from Ireland, the quality of the fleece improved. In 1796 ("I believe", he wrote many years later), he persuaded two naval officers to "to enquire if there were any wool-bearing sheep at the Cape". They brought back about twenty Spanish merino sheep, noted for their fine wool, which were distributed among favoured individuals, most of whom "did not take the necessary precautions to preserve the breed pure …. Mine were carefully guarded against an impure mixture, and increased in number and improved in the quality of their wool."[103]

Evidently, the preservation of quality sheep and the production of saleable wool required the employment of shepherds. Four years after his return to England in 1800, Henry Waterhouse, a naval officer who had also experimented with sheep farming, gave Macarthur a statement about his methods. "I trusted implicitly to the Shepherd (whom you remember) and Your occasional advice. They were driven into the Woods, after the Dew was off the Grass, driven back for the Man to get his dinner, and then taken out again until the close of the Evening; when they remained in the Yard for the Night."[104] It is clear from Waterhouse's statement that the colony's earliest shepherds did not need to be highly skilled, and Macarthur certainly did not feel that they needed to be generously paid. On a visit to England in 1803, he assured the government that Australia's "unlimited extent of luxuriant pastures" could support "millions" of sheep, "with but little expense than the hire of a few shepherds". He graciously offered to accept a grant of 20,000 acres (about 8,000 hectares) of land to give the industry the boost that it needed, seeking also "the indulgence of selecting from amongst the convicts such men for shepherds; as may, from their previous occupations, know something of the business".[105] Yet Macarthur would find it hard to recruit suitable custodians, as he himself admitted to the Bigge Commission that enquired into the state of the colony in 1820.[106] Between 1803 and 1805, the Sydney Gazette carried three advertisements seeking experienced shepherds, who "must understand the diseases incident to sheep". The first specified "a middle-aged or elderly Man of good character". The second called for "a steady, careful Man, that has been accustomed to the charge of sheep". The third required a man "of good character" and with "a good recommendation", with one adding that "[l]iberal wages will be given to any one answering the above description".[107] Skilled shepherds may have been scarce because there were still not many employment opportunities for them. At Camden, where by 1801 John Macarthur was running around one thousand sheep, they were divided into flocks numbering between 350 and 500, each supervised by a single convict shepherd. A stock survey for the colony in August 1799 returned a total of 5,103 sheep.[108] This would suggest that there could hardly have been twenty men looking after flocks in the whole of New South Wales, many of them in remote locations. Demand for shepherds increased as sheep numbers multiplied, after about 1805, and there were complaints about their "ignorance or inattention", as well as suspicions of criminal activity.[109] Numbers alone make it unlikely that the landscape term "bush", current by 1798-9, could have emerged as a by-product to jocular allusions to Shepherds Bush, although the Middlesex example could have exercised an unconscious reinforcing effect in the decades that followed.

Bushy Park Beyond the formal gardens of Hampton Court Palace lay the wider demesne of Bushy Park, all of it the property of the Crown.[110] Its part in the story comes from the versatility of convict slang, as recorded by James Hardy Vaux. As noted above, he defined "at Staines" as meaning "in pecuniary distress". But there was an alternative expression for financial problems, "at the Bush, alluding to the Bush inn at that town".[111] The Bush Inn, the principal hostelry in Staines, was the meeting place for the magistrates in the western division of Middlesex, and the justices would have dealt with cases of enforced debt repayment. The Bush almost certainly owed its name to an inn-sign that displayed a shrub. Vintners used the bush as their trade symbol (hence the proverb that "good wine needs no bush"), and the town's premier inn had no doubt adopted the name to advertise itself as an upmarket establishment.[112] In the word-play of London thieves' slang, it was a short step to transferring the term to Bushy Park, which was about eight kilometres to the east of Staines: "a man who is poor is said to be at Bushy park, or in the park". In combination, these phrases gave rise to the adjective "bush'd", which meant "poor; without money".[113] It was in keeping with his grudging attitude to "flash" that Sidney J. Baker played down the derivation of "bush'd" given by Vaux – "this could quite well be a term he picked up in Australia" – but the references to Staines and Bushy Park anchor it firmly in the London area.[114] But how might it have transferred its meaning to a description of landscape?

The link was distressingly obvious. Small settlers in New South Wales struggled with debt. This was especially the case among ex-convicts, many of whom had little previous experience of farming: of 54 former prisoners granted land before 1795, only eight were still on their farms eight years later. In 1798, Governor Hunter recognised from "the frequent bankruptcy of some of our oldest settlers that they have labored under heavy grievances and distresses". Invited to submit details of their grievances, Parramatta farmers pleaded that they were driven to "beggary" by the need to pay inflated prices for basic goods, which they blamed upon profiteers: "as the colony is now infested with dealers, pedlars, and extortioners it is absolutely necessary to extirpate them". Two years later, Parramatta settlers complained that they had "long laboured under grievances and intolerable burdens, which have not only cut off all hope of their independence, but reduced them and their families to a state of beggary and want". By then, two-thirds of all small farmers in New South Wales had abandoned their holdings.[115] As late as 1820, Commissioner J.T. Bigge thought the prospects for small settlers who lacked capital were "forbidding".[116] The Scots surgeon Peter Cunningham reckoned that three-quarters of ex-convict settlers lost their farms because they were "forced to borrow money to improve the land at such an exorbitant interest as to swallow up the whole of the proceeds". Cunningham regarded the casualties of the advancing frontier as "serving in some measure, like the American backwoodsmen, the office of pioneers to prepare the way for a more healthy population", and perhaps the rate of attrition among them was a necessary price to pay to identify those fit to survive.[117] It is understandable that textbook narratives generally take a more upbeat approach, stressing the successful establishment of agricultural settlements in the hinterland of Sydney. But it is worth stressing the extent to which the majority of small farmers had to struggle against financial hardship. If Sydneysiders described their rural counterparts and customers as at the bush, bush'd, or in Bushy Park, it would not be surprising that the core term became fused with its other overtones, to be forged as a new and specifically local word for the landscape.

There was also a Bushy Park in Ireland, eight kilometres south-west of Dublin, in what is now the suburb of Terenure. According to Wikipedia, it was originally the mansion of one Arthur Bushe, but in a neat exercise that combined rebranding with continuity, a later owner altered the name to Bushy Park in 1772. Of the 155 convicts embarked on the Queen in 1791—the first consignment from Ireland – 82 had been tried in either the City or County of Dublin.[118] The existence of a place-name element known to metropolitan felons from both England and Ireland may have made it easier to adapt its meaning to the circumstances of the new country. [See Addendum, November 2023, below, for another Irish example which would have been known to Dublin convicts, Beggars Bush.]

Bushy Park may have encouraged one further echo in Australian English. The royal parks around London provided sinecure appointments for royal (or government) favourites, who were called Rangers. For the Ranger of Bushy Park, the chief benefit was the right to live in a handsome mansion called Bushy House. At the time of the First Fleet, the Ranger was a relative of Lord North, Prime Minister from 1770 to 1782, at the time of the loss of America. In January 1797, the position passed to a more prominent figure, the Duke of Clarence (later King William IV), for whom Bushy House quickly became a favoured residence.[119] A former naval officer, he was marginally more popular than his elder brothers, the Prince of Wales and the Duke of York, although this was not saying much.[120] It is argued above that the compound term "bush-ranger", appeared in 1805, and that it originally referred to fugitives whose crimes were incidental to their survival beyond the limits of settlement. It might have expected that it would have been supplemented or superseded by a harsher designation, such as "bush bandit", for more violent outlaws. It is just possible that "bush ranger" carried some subconscious echo of the royal Ranger of Bushy Park. Too much should not be made of the suggestion, but it would be an intriguing thought that there was a line of connection between William IV and Ned Kelly.

Bushy Park, by H.B. Ziegler, 1827. In London thieves' slang, it was synonymous with financial problems.

Concluding reflections In the early twenty-first century, around 400 million people around the world speak English as their mother tongue, with unknown but at least equal numbers working in it as an acquired language, especially across much of Africa and south Asia, where it functions as an adopted lingua franca. English is a remarkably adaptable medium, constantly absorbing new words. These are often of seemingly imaginative coinage, such as "spam", for unwanted messages received by email (another recently invented term, now deeply entrenched), and "selfie", for a narcissistic photograph taken with a mobile phone, an appropriate example for this discussion, since it is believed to have originated in Australia. In an age of mass electronic media, it is often possible to trace an assumed first usage of such terms, and occasionally origin myths have arisen to account for them, comparable to the assertion that the Australian term "bush" came from South Africa. Yet the etymology of neologisms is rarely conclusive and, in many cases, derivations remain utterly obscure. Even more puzzling is the process by which some words get into circulation, as if by some process of overnight global alchemy, while presumably many others fail to gain general acceptance.

These reflections may put the quest to explain the origins of "bush" into some perspective. A census in June 1799 counted a European population of 4,746 in New South Wales, of whom 812 were children. We are thus studying a seedbed for new vocabulary not of 400 million native English speakers, but of around four thousand. The linguistic crucible was probably much smaller than the total number of adults. Sydney accounted for half the population, and new words almost certainly would have forced their way into circulation in the bustle of the colony's only town much faster than in the isolated and lonely homesteads of Parramatta and Hawkesbury farmers. Across the colony, around 2,200 inhabitants were either convicts or soldiers, the two categories being brought into close contact by the guard duties performed by the New South Wales Corps. Ex-convicts of course made up most of the remainder, for the colony's official administrative class was very small. When the soldiers John Brown and Thomas Turner attributed the term "bush" to a recently arrived convict, they had probably coordinated their evidence, but they evidently felt confident that their choice of vocabulary was credible. It does not seem that the court required a translation, but it is important to appreciate that the term "bush", used to describe landscape, was created from below and its adoption resisted by those who wielded authority – and created most of the records – in the colony.

It was never plausible to assume a South African Dutch origin for a term that emerged from precisely the section of New South Wales society who were forbidden to land at Cape Town. Revisiting the subject half a century on confirms that only the exceptional circumstances of sickness or shipwreck may have allowed small numbers of sailors and convicts to spend brief periods ashore. Officers were keen to spend as short a time in port as possible, and showed little interest in the locality or its culture. In addition, it may be added that English-speaking South Africans only encountered bush, in the form of thick vegetation in the eastern Cape or in the plateau country of the Transvaal, decades later, long after the term had acquired its own connotations in Australia. This is not to deny that the English and Dutch words probably share a common west Germanic origin many centuries ago, but there is no reason to suspect any more recent convergence.[121]