From Little Ilford to Botany Bay: Frances Davis, cross-dressing First Fleeter

Frances Davis was a convict sent to New South Wales on Australia's First Fleet in 1787. Identified as "late of the parish of Little Ilford in the co[unty] of Essex Spinster", she was about twenty years of age. Her record showed that she was guilty of a major crime by breaking into the house of Agnes Bennett, widow, on 2 September 1785, and stealing cash and bills of exchange worth over £800 from John Wigglesworth.

Frances Davis was originally sentenced to death, but this was commuted to fourteen years' transportation.[1] This essay attempts to identify her, through the crime she committed, and place her in the context of the First Fleet's voyage to New South Wales, and her likely experiences in the early years of the colony. The approach carries its own dangers, for attempts to associate documented events with an individual who is known to have witnessed them may risk shading into the realm of the historical novel. Frustrating, too, is the problem that Frances Davis remains a tantalisingly elusive figure.

Botany Bay and Little Ilford I became interested in Frances Davis through both ends of her story. Early in my own career, I took part in what was known as the Botany Bay debate, an amiable and essentially speculative controversy among historians which sought to explain why the British government had decided, in 1786, to establish a convict colony in distant New South Wales.[2] Traditionally – and part of Australia's founding myth – the insensitive British had simply dumped a selection of their criminals on the other side of the world once the independence of the United States meant they could no longer be disposed of across the Atlantic. The corresponding Australian achievement in building a nation upon such unpromising foundations was, of course, all the more noble and praiseworthy. In the mid-twentieth century, more imaginative historians put forward hypotheses suggesting positive motives behind the project. One theory linked the establishment of New South Wales to British attempts to open trade with China. Another argued that the real motive lay in the need to develop flax supplies, for rope and sailcloth, and to exploit alternative supplies of storm-resistant mast timber, Australian eucalypts and New Zealand kauri replacing the pine forests of New England as strategic resources for the Royal Navy.

In contrast to most academic debates, the ensuing controversy was hugely enjoyable, not least because it highlighted basic methodological issues. The available documentary evidence was not particularly helpful. Of the two major sources, one was a freelance enthusiast's "rough outline of the many advantages that may result to this nation from a settlement made on the coast of New South Wales", which may or may not have persuaded policy-makers. The other was an official blueprint of August 1786, ordering the Treasury to provide a detailed list of clothing and tools for the expedition, very much a "how to" rather than a "why" document.

In the absence of persuasive written evidence, historians wondered whether the intention behind the establishment of the colony might be deduced by looking at the people actually dragged out of the gaols and loaded on to the convict transports. Was it possible to infer the existence of some selection process that searched out specific skills, and hence might provide clues to the function of the colony? (By and large, the answer here had to be in the negative: the convicts proved to be singularly useless, which was probably why they had betaken themselves to crime, in which they were also generally unsuccessful.) In particular, it was seemed potentially fruitful to look at the women – there were 193 female convicts, compared with 582 men. Had they been selected to become the partners and mothers of reformed felons? Here, the line of speculation led to individuals such as Frances Davis, young enough to produce children but (apparently, given her fourteen-year sentence) guilty of such a brazen heist that her qualifications for responsible motherhood might be doubted.

By coincidence, I also approached the role of Frances Davis in the founding of Australia from the other end of the world. Having an interest in the history of Essex, I was intrigued by her reported residence in the parish of Little Ilford. The name was phased out in the late nineteenth century, replaced by Manor Park, invented for the suburban railway station opened in 1872. As an administrative unit, Little Ilford was merged with nearby East Ham in 1886.[3] It probably owed its eight centuries of separate existence to a Norman land-grabber who wanted an estate accessible to London by navigable water: Normans often built chapels on their estates to control the tithes. Little Ilford adjoined a ford across the River Roding, which preserved what is assumed to have been its Celtic name. The parish was bisected by the main Essex highway, which ran east-to-west towards London. By the sixteenth century, Great Ilford, a roadside town, had developed on the east side of the Roding, and this became the nucleus of the modern suburb of Ilford, partly explaining the eclipse of the smaller settlement. Everything about Little Ilford was small. A nineteenth-century historian thought its parish church "as plain and unadorned as a parish school-house"; in 1954, the architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner called it "not impressive though loveable".[4] It hardly needed to be larger: the parish was about one square mile in area, and, in 1792, contained just fifteen houses.[5] Of course, there is no innate reason why so small a community should not produce a dangerous criminal, but it did seem incongruous that a female desperado aged just eighteen should originate in this obscure parish of fewer than one hundred people.[6]

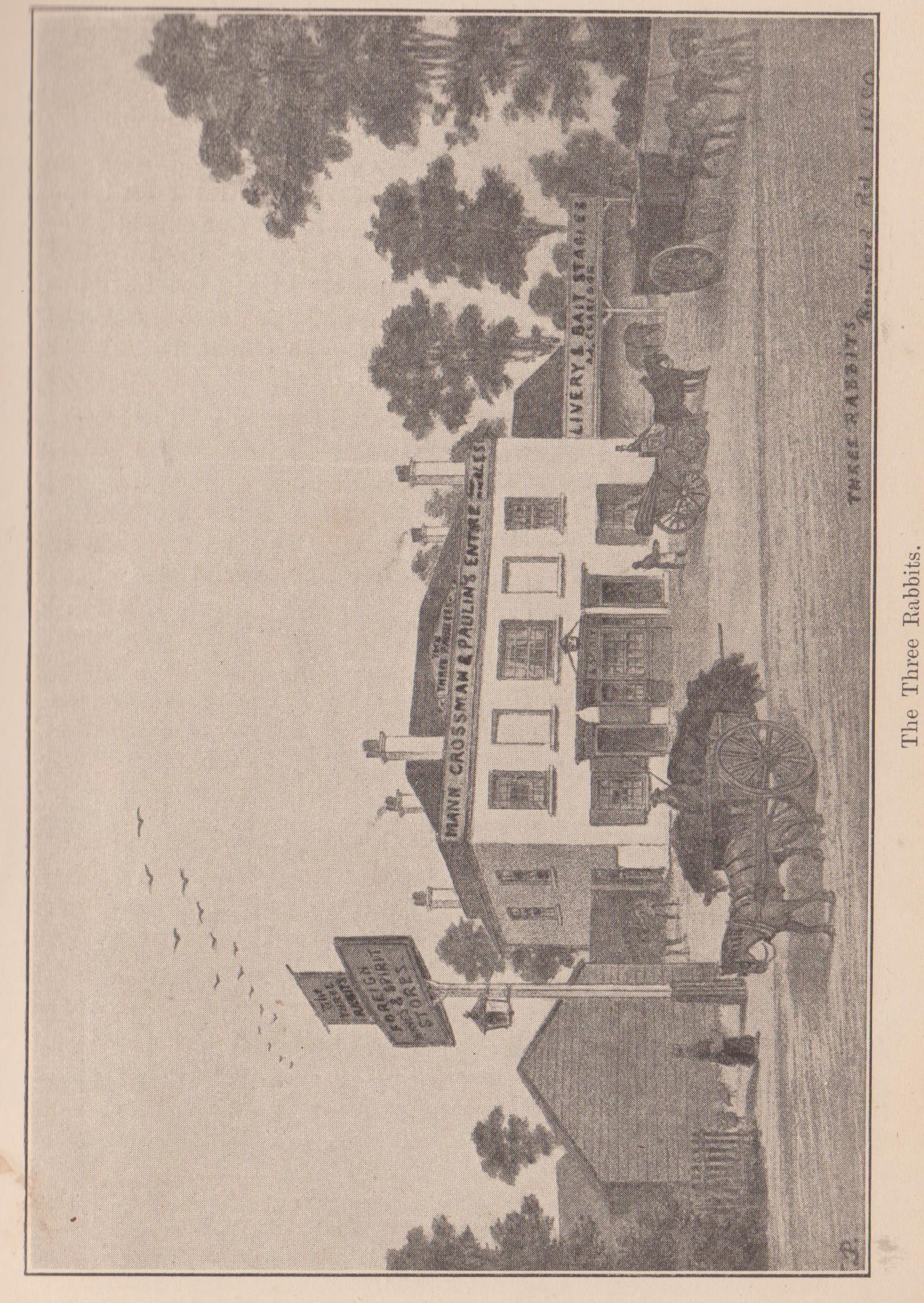

The key to understanding both the low density of Little Ilford's population and – as it would turn out – the transient nature of its association with Frances Davis lay on the parish's northern flank, which extended into a belt of heathland called Wanstead Flats. From its proximity to London, Essex was cattle-raising country. Driven from all parts of Great Britain, beasts arrived on the capital's doorstep scrawny from their trek, and were fattened on the lush marshland pastures beside the Thames before making their final journey to market. Although officially a detached part of Epping Forest, the broad and level ground of the treeless Flats provided an ideal location for an extended cattle fair, which operated from February to May each year. A 1794 survey of Little Ilford came close to seeing the cattle fair as its raison d'être: "A great part of the business between the dealers is transacted at the Rabbits in this parish, on the high road."[7] Officially styled the Three Rabbits, the hostelry is perhaps best remembered for its appearance in Thomas Hood's novel of 1834, Tylney Hall, where its primitive inn sign was likened to "three Chinese pigs with long ears".[8] It was under the roof of the Rabbits on 2 September 1785 that Frances Davis committed the daring crime that sent her to Botany Bay, providing the legal fiction that identified her, for a single night, as a resident of the parish of Little Ilford.

Mr Wigglesworth goes to Town John Wigglesworth was described as a "capital grazier", a large-scale cattle dealer, probably also – to borrow an American expression – a rancher.[9] His surname suggests that he was a Yorkshireman, but in 1785 he was living at Gosfield in Essex, where he doubled as an innkeeper and as agent for cattle farmers from Lincolnshire and Scotland.[10] Gosfield Hall was one of the largest mansions in Essex, and one of the few in the county to be occupied by a titled aristocrat, Earl Nugent. His successor, the Marquess of Buckingham, lent the house to the exiled French king, Louis XVIII, who (literally) held court there. Nugent had laid out the park on a grand scale, and it is likely that Wigglesworth rented access for intensive short-term grazing: the grass in aristocratic demesnes did not mow itself.[11]

At the end of August 1785, John Wigglesworth made arrangements to visit London's Smithfield Market, intending to purchase young cattle to be fattened for sale the following year. He planned to operate on a gigantic scale: reports of the exact amount he was carrying vary, but the total was close to £1250. One calculation of the changing value of sterling would put the 2020 purchasing power at just short of £200,000, around $A350,000. On 30 August he arranged a bill of exchange for £400 with the Norwich Bank, probably through local agents in the nearby towns of Halstead or Braintree. Bills of exchange were effectively bank cheques, which could be transferred by endorsement. Although vulnerable to forgery, in practice they provided greater security than cash: Wigglesworth carried four of them, with a total value of over £650. He also took £178 in cash, and a sizeable sum in banknotes. On 2 September, he set off for London, probably on horseback,[12] with his cash, notes and bills in canvas bag, which a court official later punctiliously valued at one penny.

Even given his precautionary transfer of cash into bills of exchange, Wigglesworth must have known he was taking a huge risk. The main Essex road was notorious for highway robberies. Built by the Romans, its long straight stretches made it easy for marauders to identify unaccompanied travellers. Escape was assisted by a nearby belt of common land which spread across the northern part of the royal manor of Havering and into the woodlands of Hainault Forest. Robberies occurred relatively frequently in the Romford-Ilford area, which Wigglesworth would have reached relatively late in the day. In fact, he had obviously planned to break his journey, a forty-mile ride from Gosfield to Little Ilford being enough for a single day. He would have known the Three Rabbits from visits to the Wanstead Flats cattle fair. No doubt the landlady, the widow Agnes Bennett, made him welcome both as a regular customer and as a fellow innkeeper. Although the annual fair had finished four months earlier, it was likely that the Three Rabbits was patronised by passing cattlemen year-round. John Wigglesworth no doubt looked forward to a convivial evening of grazier gossip, with perhaps the chance to meet people who might be the key to future deals. (There is a picture of the Three Rabbits around 1880 at the end of the text. It was not a very large hostelry.)

Wigglesworth did indeed make a new acquaintance, a young man who claimed to be a horse dealer, and evidently radiated admiration for the older man and indicated a wish to learn from his experience and benefit from his wisdom. The horse-dealer was in fact Frances Davis, garbed in men's clothing. When revealed, her imposture created a sensation, all the greater because initial reports claimed, inaccurately, that the two had shared a bedchamber – where, given the absence of bathroom facilities and the general lack of privacy, it would have been virtually impossible to have maintained the deception. Nonetheless, her performance remains both impressive and intriguing. In woman's clothing, Frances Davis was described as "extremely handsome" and – perhaps curiously – she was easily identified by the chambermaid at the Three Rabbits. To have disguised her female form, she presumably wore a heavy and baggy male outfit, a difficult act to carry off in late summer. Did she perhaps scrape her face to inflict alleged shaving cuts? In addition to her gender deception, she must also have acted as if she were some years older than eighteen in order plausibly to pass herself off as a horse-dealer. Contemporary journalists were also shocked to learn that Frances Davis had "ingratiated" herself with Wigglesworth by smoking a pipe with him, an exercise that was all the more daring because the tobacco was apparently stored in the canvas bag that contained his working capital. In fact, Frances Davis could probably have deduced that her intended victim was carrying a large amount of money simply from his conversation. Indeed, she may not have realised just how much she was planning to steal: there are thefts that prove too successful for the criminal and this was probably one of them.

Intending to rise early the next morning to head for Smithfield, Wigglesworth took an early supper and retired to bed. As a safety precaution, he wrapped the canvas bag in his breeches, placing both under his pillow. At some point as he slept – the charge sheet put it at "about the hour of one in the night" – Frances Davis crept into his room and "found means to convey the notes and money" from under the pillow. Wigglesworth woke at about seven o'clock to find that both his canvas bag and his new friend had disappeared. It is often assumed that London lacked effective policing before Peel instituted the modern constabulary in 1829. Certainly, the upholding of law and the enforcement of order were poorly performed. However, in various parts of the metropolis, magistrates' courts were equipped with small numbers of thief-takers, although the best-known of them, at Bow Street, had a staff of just six in 1780, the year of the Gordon Riots.[13] Wigglesworth despatched urgent messages to the various law enforcement agencies, and the sheer scale of the robbery ensured that the crime received prompt attention.

An arrest is made In fact, it was the thief herself who ensured that the case was quickly solved. The finesse with which Frances Davis had carried out her crime was not matched by the judgement that she displayed immediately afterwards. On returning to London on the Saturday morning, she had cashed several of the banknotes at various shops, no doubt calculating that it made sense to unload stolen property before it became too hot to handle. (It was not reported whether she maintained her male persona for these transactions: a teenage girl handling large sums of money would perhaps have aroused suspicion.) At that point, having had little sleep the previous night, she might well have gone to ground and gone to bed. Instead, perhaps buoyed up by her adventure, she headed for surely the least appropriate venue in London – Newgate prison. There she visited a "female convict", to whom she gave a present of "a pair of silver buckles, and other trifling articles" and – it was later reported – "boasted of her exploit". This strange episode is one of the clues that may suggest that Frances Davis was bisexual, although historians should be wary about suggesting gender attributions in an area where evidence is necessarily opaque. Perhaps the two women were simply friends: if so, the exultant thief's trust was badly misplaced. "The woman being a favourite of the executioner's, she communicated the matter to him", no doubt preferring the chance of freedom to the silver buckles. On the following day, Sunday, Frances Davis was tracked down by Bow Street officers at "an obscure lodging" in The Mint, a slum district south of London Bridge, surrounding the modern Southwark Cathedral. "Eight hundred pounds in notes and cash were found concealed in her cloaths." Her "boy's apparel" was also seized. Wigglesworth identified the money, and a chambermaid from the Three Rabbits "ascertained" that Frances Davis was the vanished horse dealer. Although she was undoubtedly cornered, the accused "denied any knowledge of the transaction with great composure."

There is some mystery here: how was it that, on the second day after such a major heist, Frances Davis retained so much of the loot? "It is said she is connected with a numerous gang, and has long been employed in robberies similar to the above iniquitous transaction," was the closing statement in one news report. It would certainly have been useful to have had accomplices for an efficient getaway from the inn, but if she had been whisked off to the crime bosses, they would surely have relieved her of the proceeds. Had she double-crossed the gang leaders? Bills and cash worth around £350 remained missing at the time of her trial six months later. Had she given this amount to associates, while concealing the rest?

Trial and sentence Frances Davis was tried at the Essex Assizes on 6 March 1786. The indictment elevated her sneaking into Wigglesworth's bedchamber into a charge of breaking-and-entering, the implication of force adding to the severity of the allegations against her. The newspapers had already convicted "the celebrated Frances Davis", and relished the opportunity once again to narrate the "extraordinary manner" in which she had carried off her deception and carried out her crime. The jury's guilty verdict was more or less automatic, and the judge, Sir William Ashhurst, promptly sentenced her to death, commenting "that from the art and address with which the robbery was planned and completed, he did not think it could have been her first offence ... and therefore advised her not to flatter to [sic] herself that, in this case, her sex could afford her any protection".[14] By contemporary standards, the sentence was fair: she had committed a capital crime, and must have known that she risked being hanged. But the verdict had undoubtedly been filtered through an assumption of other crimes for which she had not formally stood trial. Newspaper reports insisted that "she has been the terror of this country [meaning Essex] for some years back", which was a sweeping claim in relation to a woman of eighteen.

Assize courts were not shy of handing out death sentences, but relatively few of those condemned actually went to the gallows. Judges reported to the government on each capital case, frequently using loopholes or excuses to recommend commutation. However, reports suggested that Frances Davis was doing no favours to her chances of survival, still refusing to disclose the whereabouts of the remaining £350, and it was assumed that Ashhurst would "leave her for execution". Perhaps she was lucky in encountering a judge who was described as "a man of liberal education and enlarged notions", although a modern study concludes that he was sparing in the recommendation of mercy.[15] Whatever his motivation, before he left Chelmsford on circuit, Ashhurst recommended mercy for most of those condemned to death, including Frances Davis. Her sentence was formally reduced to fourteen years' transportation on 10 April. In the spring of 1786, there were no plans for a convict settlement at the other end of the world, so we may rule out any wish to select healthy female breeding stock to contribute to a future colonial population.

Nor, at that time, did the government have any other planned outlet for felons lagged for transportation. However, in August 1786 the decision was taken to establish a new penal settlement in New South Wales, and this almost certainly shaped the subsequent fate of Frances Davis. She was still in Chelmsford Gaol when the Home Secretary, Lord Sydney, ordered her transfer to London in November 1786. It is likely that she travelled from Chelmsford perched on one of the lumbering goods wagons that ran between the capital and the countryside. These incidentally provided a cheap mode of travel for poor people who could not afford stagecoaches. Frances Davis would have been tethered to prevent escape, and accompanied by a constable or a prison officer. This would have made her the subject of attention and probably also of derision along the high road to London, a route that passed the Three Rabbits. Since the livelihoods of chambermaids and stable boys would be threatened if notoriety deterred travellers from staying at the inn, we may perhaps imagine them turning out to jeer the "celebrated Frances Davis" on the first stage of her journey to Botany Bay. She was transferred to the convict ship, Lady Penrhyn, at Gravesend on 31 January 1787. This confined and crowded space would be her home for 53 weeks, until 6 February 1788.

By November 1786, planning for the Botany Bay project was well advanced: was Frances Davis perhaps regarded as potentially useful in the establishment of the colony? Unfortunately, the only information about her qualifications seems to be a single-word note in the list of convicts on the Lady Penrhyn, compiled by the ship's surgeon, Arthur Bowes, which simply identified her previous occupation as "Service". For tens of thousands of girls from poor backgrounds, domestic service – skivvying – was the obvious and maybe the only honest available employment. There is no recorded assessment, either in England or in Australia, suggesting that she possessed any particularly useful skills. The case of Frances Davis tells us nothing about the motives behind the decision to send convicts halfway around the world.

The Lady Penrhyn Reconstructing the experience of individual convicts in early Australia is a tantalising but frustrating exercise. The New South Wales colony quickly generated extensive records, which may be supplemented by the narratives compiled by officials on the First Fleet. There are many episodes which the historian can be sure were witnessed by Frances Davis, but few if any points where her involvement, and still less her reactions, can be documented. The journal of the ship's surgeon Arthur Bowes throws interesting light on the voyage of the Lady Penrhyn, but she is not one of the dozen or so women whom he specifically mentioned.[16] The Lady Penrhyn was 31.3 metres in length and 8.2 metres at its widest point, less than half the size of modern-day ferries across the Thames or Sydney Harbour.[17] Although the expedition to New South Wales would be its maiden voyage, the ship had apparently been built for the slave trade, and designed to carry 275 enslaved Africans.[18] The fact that around one hundred female convicts were loaded aboard the Lady Penrhyn does not mean that they travelled in dignified comfort. In addition to around forty officers and crew, the ship also carried a detachment of marines and their officers – possibly another forty men – as well as two surgeons plus a passenger who had presumably bought a ticket, much to the surprise of the expedition's commander, Governor Arthur Phillip, who only learned of his presence at Cape Town.[19] Two of the officers were accompanied by children. One convict woman managed to bring along her fifteen year-old son, another her eight year-old daughter: at various times, the Lady Penrhyn carried twenty children under the age of four, some of them born at sea, where five of them would die. The ship also carried livestock: seven horses were purchased at Cape Town.[20] There was not much room aboard.[21]

It is hardly necessary to emphasise that an eight-month ocean voyage on the 337-tonne Lady Penrhyn was a dangerous venture. As Samuel Johnson had observed of seafaring generally, "being in a ship is being in a jail, with the chance of being drowned."[22] The First Fleet sailed as a convoy, with the Lady Penrhyn usually the laggard, but the vessels were rarely close enough to be capable of rendering mutual assistance in a crisis.[23] Since they were usually confined below decks, convicts were particularly at risk. On 10 January 1788, sailing about 800 kilometres south of Sydney, the Fleet was battered by a sudden and very violent storm. On board the Lady Penrhyn, the women were "so terrified that most of them were down on their knees at prayers," although Bowes grimly noted that "in less than one hour after it had abated, they were uttering the most horrid Oaths & imprecations that c[oul]d proceed out of the mouths of such abandon'd Prostitutes as they are!"[24] Bowes also noted several instances where women were injured by falls that were no doubt caused by the pitching of the ship. It is likely – although he does not mention the practice – that they were allowed on deck to take exercise in calmer weather, probably in small groups and tethered for security. This, at least, made it less likely that any of them would go over the side.

Two women died on the voyage. One, Elizabeth Beckford, was certainly in her seventies, and Bowes believed she was 82. Her death from "dropsy" was probably caused by heart disease. The other, Jane Parkinson, died from "consumption", probably tuberculosis, an infection that could easily spread in confined spaces. The administrative decision to send Beckford and Parkinson on a long and expensive voyage does not suggest any careful vetting process designed to identify useful skills. There was no dignity surrounding death in the packed hold of a convict ship, and no discreet way for the living to avoid its reality. The third mate of the Lady Penrhyn read the burial service for Elizabeth Beckford, and her body was consigned to the deep within an hour of her death.[25]

If the convicts were menaced by natural hazards that were random and intermittent, they also faced constant threats from dangers that were, literally, man-made. Although there was a two-to-one female-to-male ratio on the Lady Penrhyn, the gendered power relationship was brutal and naked. Early in the voyage, the defiant behaviour of a couple of the women led male authority to conclude that it was "absolutely necessary to inflict corporal punishment upon them": the offenders were flogged across their bare buttocks with the cat of nine tails. When the victims challenged the legitimacy of their correction with a flood of abuse, they were gagged, a dangerous proceeding that risked causing cardiac arrest. However, the practice was "totally laid aside" before the ship had even reached the mid-Atlantic, "as there are certain seasons when such a mode of punishment c[oul]d not be inflicted with that attention to decency wh[ich] everyone whose province it was to punish them, wished to adhere to". Although untroubled by the obscenity of physical violence, the masculine power structure had too much delicacy of feeling to cope with the natural cycle of menstruation. Instead, refractory females were handcuffed, subjected to thumbscrews or, in extreme cases, had their heads shaved, "which they seemed to dislike more than any other punishment they underwent."[26]

Violent discipline formed part of the context of rampant sexual exploitation. As the Fleet lay off Portsmouth in April 1787, Lieutenant George Johnston, commander of the marines, "issued orders to keep the Women from the Sailors". A few nights later, he held an unannounced roll-call in the women's quarters. Five of them were found to be consorting with members of the crew, one of them the second mate, whom Johnston sought to have dismissed; the women were put in irons.[27] By the time the First Fleet reached Botany Bay, Johnston was living with 21 year-old Esther Abrahams, a convicted shoplifter from London: they would marry 26 years later.[28]

Not surprisingly, the women exploited the only resource at their command, their sexuality. If the men wanted them, they would have to pay for the privilege. If they were to be abused as prostitutes, they might as well reap the benefits of the trade. In March 1786, Phillip had severely criticised the magistrates who had despatched female convicts to the Lady Penrhyn, even accusing them of "infamy". The women were "almost naked" and so "filthy" that fever had broken out among them.[29] However, when the convicts disembarked eleven months later, Bowes noted that the women "were dress'd in general very clean & some few among them might be s[ai]d to be well dress'd." Indeed, when they were issued with "Slops" – standard utility clothing – on leaving the ship, one recipient indignantly threw them down on the deck.[30] The women were able to maintain this lifestyle by manipulating the crew, "who have at every Port they have arrived at spent almost the whole of their wages due to them in purchasing different Articles of wearing apparel & other things for their accommodation".[31]

It is possible to recreate something of the fraught atmosphere aboard the Lady Penrhyn, but Frances Davis remains hidden in plain historical sight. It would have been impossible to avoid the scenes of death and of childbirth, but no record survives – and probably none was compiled – which might tell whether her head was shaved or her buttocks were flayed. It is tempting, if ultimately futile, to engage in empathetic speculation. For instance, on 2 September 1787, the First Fleet was anchored off Rio de Janeiro. The convicts were probably denied access to a calendar, and Frances Davis may not have been aware that it was the second anniversary of her spectacular crime at the Three Rabbits. Did she perhaps fantasise about using her talent for disguise to attempt an escape? In one of his diatribes, Bowes condemned many of the women for "plundering the Sailors … of their necessary cloaths & cutting them up for some purpose of their own." Could this have included the manufacture of suitably adapted male attire that might have enabled Frances Davis to pose as a seaman? The chief problem, of course, would have been to get ashore – and what then? A male convict who managed to hijack a small boat and decamp at Tenerife was recaptured with such ease that he was barely punished for his hopeless initiative.[32] The fugitive had tried – and failed – to secure employment on a foreign merchantman: the challenges of language and gender would have been far greater for Frances Davis.

Despite her overall invisibility on board ship, Frances Davis appears first in the list of convicts compiled by Bowes. This may be coincidence, but Bowes was an Essex man, and perhaps he was particularly interested to encounter so notable a star of the Chelmsford assizes. She was one of only eight felons among the total of 109 sentenced to more than seven years' transportation, four being despatched for life and four more, including herself, sent abroad for fourteen years. There is no indication that her longer sentence either conferred honour among thieves or implied more severe treatment by her gaolers. She seems to have formed a friendship with Mary Marshall, a London shoplifter, who was about ten years older, although the documentary evidence for a link between them dates only from 1808.[33] It is also possible, although unproven, that she formed a friendship with Esther Abrahams, who had given birth to a baby shortly before the Lady Penrhyn sailed, and would have needed help with child-minding while she was providing comforts for Lieutenant Johnston.

New South Wales and Norfolk Island When the convicts were disembarked in February 1788, Frances Davis once again fades into the background so far as documentary records are concerned. She must have been somewhere in the mayhem that ensued when discipline collapsed after the women came ashore on 6 February. She would have been one of the company of convicts assembled eleven days later to watch one of their number drop to his death from the branch of a eucalyptus tree, a spectacle designed to deter thieving. Even by the standards of public executions, it was a frozen moment of horror, as the convict deputed to act as hangman could not bring himself to loop the noose around the condemned man's neck, only performing his duty when he was threatened with being shot.[34] Frances Davis probably recalled the moment, two years earlier, when Justice Ashhurst donned his black cap and glared bleakly towards her in the dock. We cannot recapture life in those pioneer days at Sydney Cove without appreciating the pervasive atmosphere of capricious sadism imposed by the gaolers upon the gaoled.

When the First Fleet storeships, Fishburn and Golden Grove, returned to Britain in November 1788, an enterprising and highly literate female convict smuggled out a letter bemoaning her "disconsolate situation in this solitary waste of the creation." The voyage to New South Wales had been "tolerably favourable", but the subsequent "inconveniences" caused by "want of shelter, bedding, &c., are not to be imagined by any stranger." In the absence of glass, the windows in their "miserable huts" were filled with "lattices of twigs". Food was indifferent, and rendered "insipid" from a shortage of salt. Meat from "kingaroo rats" tasted like a leaner version of mutton, while "there is a kind of chickweed so much in taste like our spinach that no difference can be discerned." Worse than the hardships was the physical danger. The Aborigines "still continue to do us all the injury they can, which makes the soldiers' duty very hard, and much dissatisfaction among the officers. I know not how many of our people have been killed." This, of course, was a problem that might have been foreseen by the politicians and officials who took the decision to occupy a territory on the far side of the planet.

Thus far, the writer had described challenges that affected everyone in the settlement, irrespective of gender or status. But she also made it clear that "the distresses of the women" were "past description". They were "totally unprovided with clothes" and "those that have young children are quite wretched". While there had been some marriages, "several women, who became pregnant on the voyage, and are since left by their partners, who have returned to England, are not likely even here to form any fresh connections." The letter confirmed that female convicts had exploited their sexuality to secure favours on board ship. At Sydney Cove, they particularly felt "the deprivation of tea and other things" which they had been "indulged in ... by the seamen".[35]

As she had done on board the Lady Penrhyn, Frances Davis kept a low profile through that first year ashore. Indeed, she re-surfaces in the historical record thanks to a touch of humanity. Susannah Allen, another London burglar, died in childbirth in October 1789, leaving an infant daughter who was christened Rebekah. Although the identity of the father was known – he was a private in the marines – there was (of course) no question of his assuming any parental responsibility: in fact, as one of the colony's less literate officials noted that, by so thoughtlessly dying, Susannah Allen had "left the infant Bestard". Instead, magistrates handed the baby to Frances Davis, who was effectively permitted to adopt the child "so long as she did justice to it". In her study of Australia's Founding Mothers, Helen Heney pointed out that the colony had no milk supply at the time, and its entire population was in fact uncomfortably close to starvation.[36] It would probably have been normal practice to entrust an orphaned baby to a wet nurse, possibly a woman who had recently lost a child of her own but could still provide vital breast milk. However, birth records seem to have been comprehensive in early New South Wales, and there is no indication that Frances Davis ever had a child of her own. It is certainly interesting that somebody who could so impressively pass herself off as a man should have been chosen as a foster mother, and on terms that may suggest enthusiasm for the role on her part. It is likely that she was already caring for the baby. Her selection as guardian for baby Rebekah tends to add plausibility to the hypothesis that she had contributed to child care aboard the Lady Penrhyn. Sadly, the child died in February 1790, but it seems reasonable to quote Heney's assessment: "it is surprising, and a tribute to Frances's care and skill, that she was able to keep a child deprived of breast-feeding alive as long as she did."[37]

Within weeks, Frances Davis was on the move, sailing for Norfolk Island on board the Sirius on 4 March 1790.[38] The transfer is yet another mystery in her saga. The island settlement, 1400 kilometres into the Pacific Ocean, would later become a place of punishment, but – surprising though it may seem – the first convicts from the Lady Penrhyn selected to go there were chosen for their good behaviour on board ship.[39] There is certainly no indication that Frances Davis had committed any offence that might have been punished with further exile, while her recent work as a foster mother ought to have stood her in good stead with the authorities. The explanation may lie in the life of Esther Abrahams, who had just given birth to the first of the large brood of children that she would present to her by-now firmly established partner, George Johnston, who had been promoted and appointed to command the marines on Norfolk Island. Esther's baby, George junior, was baptised on 4 March 1790. Boarding the Sirius two days later, she was hardly in an ideal state for a an indeterminate voyage in a tossing ship on the high seas. She already had a daughter, not quite two years old.[40] Perhaps she lobbied for the inclusion of a trusted companion with recent child-minding experience?

However, there is a more straightforward and less specific explanation for the despatch of Frances Davis. By early 1790, the New South Wales colony had worked its way through two years' stock of the provisions brought from England. There was little prospect of self-sufficiency and no news of further supplies from Britain. "Vigorous measures were become indispensable," wrote Watkin Tench. Phillip decided to send around two hundred convicts to Norfolk Island, "it being hoped that such a division of our numbers would increase the means of subsistence, by diversified exertions."[41] Norfolk Island had a natural supply of seabirds and a promising potential, at least in calm weather, for fishing. Since land had been cleared for garden work, it made sense to send female convicts, who were less suited to the backbreaking struggle with the unforgiving soil of the mainland. Frances Davis was one of 67 despatched in March 1790; a further 157 from the Second Fleet followed in August.[42] Fortunately for historians, the first contingent was accompanied by one of the colony's diarists, Lieutenant Ralph Clark.[43]

Favourable winds and boisterous seas carried HMS Sirius to Norfolk Island in a remarkably brief voyage of eight days. The downside of the swift passage was that most of those aboard suffered from seasickness. Of the female convicts, Clark noted, "there is not one but what is Sea Sick", and "between decks there is Such a disagreeable Smell from the women that are Sea Sick that it is a nuff to Suffocate one".[44] Further challenges followed their arrival, for Norfolk Island had no harbour. "I never landed in Such a Bad place in my life," Clark commented. A boat carrying some of the women and children ashore was almost swamped by the ocean swell. "I wonder that the Boat [was] not lost and every body in her for the women would not Sit Still but made a terrible noise". Danger was followed by disaster: as the Sirius attempted to manoeuvre its way towards shore, it struck a reef and foundered. Crew and convicts were rescued, but most of the supplies (and Clark's baggage) were lost.[45]

If Frances Davis had hoped she was being transferred to a South Seas paradise, she would have been seriously disappointed. Five hundred people faced the prospect of starvation. In mid-May, Clark commented that "the people in General begin to look very bad from the Shortness of the allowance and from all appearances it will be worse with use all before it is better I am affraid."[46] Clark's reported condemnation of female convicts as "those damned whores!" has given him a niche in Australian historiography, providing a label for one of the alleged stereotypes through which the country's womenfolk have conventionally been viewed by its dominant male culture.[47] Hence his very occasional sympathetic allusions to their plight carry all the more descriptive weight. The women were employed in pulling out roots grubbed up by male labour to clear ground for cultivation. When blight got into the maize crop, female convicts were sent in to clear the patches. Some were detailed to pull caterpillars from the crops, other were used to harvest potatoes. In November 1790, the entire female population was mobilised to assist in "the Flax Business", the absence of any sense of urgency throwing its own light upon the argument by some historians that the Botany Bay project had been driven by a desire to utilise this resource. By February 1791, even Clark felt sorry for the "poor devils" who by now had almost no clothes to wear: as Clark put it, "some of them had not So much peticoat as would cover their commical cuck".[48]

Although the threat of outright starvation was reduced by the arrival of supply ships in August 1790, the additional numbers of convicts they brought still required tight control over the distribution of rations. This was enforced by an increasingly cruel regime of corporal punishment, imposed without distinction of gender. On one occasion, even the flogger was flogged for displaying an insufficient degree of sadism. Women received sentences of between ten and 75 lashes. Some were granted partial remission after passing out while being punished: Clark "forgave" Mary Higgins after the infliction of 26 of her 50 strokes because she was "an old woman", although he hoped her fate "will be a warning to the Ladies". In his journal, he noted the names of 28 women who were flogged. A twenty-ninth was confined to irons for theft: "She is big with child otherwise Should have flogged her Yesterday for she is a D[amned] B[itch]."[49] During the seventeen months that he was on Norfolk Island, the women faced roughly a one in eight chance of being lashed to the triangles and pulverised. Those odds presumably shortened the longer a convict spent there. Frances Davis remained on the island until March 1793.[50]

The last 35 years Perhaps the most interesting, if unfortunately mysterious, key to understanding the rest of the life of Frances Davis is the statement on the headstone erected following her death in 1828 in Sydney that she had revisited England three times.[51] She would have served her fourteen-year sentence of transportation by 1801, the year in which she was listed as "gone to England".[52] There is no record of her having received a ticket of leave, which would have allowed her to work for wages on her own behalf, and hence no way of knowing how she managed to finance a return journey. [See: Tailpiece on this.] However, she was back in New South Wales by 1811, when she married Martin Mintz. She was described as a widow, which (if accurate) means that she had married in England, perhaps using an inheritance from her first husband to bring her back to Sydney. Mary Marshall, presumably a friend since their Lady Penrhyn days, was a witness at the wedding.

Martin Mintz is believed to have arrived in the colony in 1791, where he served as a member of the New South Wales Corps. Nothing is known of his origins, but his name may suggest that he came from Germany. He left the Corps in 1803, and tried farming on the Hawkesbury River, marrying a convict woman two years later. She died in October 1810, and the marriage to Frances Davies took place three months later.[53] The couple settled in Sydney, where they seem to have operated a bakery in Clarence Street.

Her marriage to Martin Mintz ended quickly, and in tragedy. The Clarence Street business ran into financial difficulties: the claim on her headstone that Frances Mintz was "much respected by all who knew her" would seem to imply that she was not at fault. In July 1813, Mintz went missing. A week later, his decomposed body was recovered from the south side of the harbour opposite Garden Island. An inquest determined that the "unfortunate man" had "drowned himself in consequence of some pecuniary embarrassments".[54] Nothing was reported of the grief of his widow.

Presumably, her two further visits to Britain occurred between 1813 and 1828, but no information about them survives. The only clue is that she secured a certificate, an identity document attesting to her status as a free woman, in September 1823, under her maiden name of Frances Davis and specifically identifying her as having arrived on the Lady Penrhyn.[55] Returning to England while under sentence of transportation was a serious offence, and the certificate would have served as a passport, although it also had many uses within the colony: several dozen were issued in the week that she applied. But precisely when she travelled, let alone why and how, remains a mystery. Presumably, her first return journey, in 1801, had been intended as repatriation to her homeland, subsequently underlined by a first marriage. Something then brought her back to New South Wales. From the fact that her marriage to Martin Mintz took place just three months after the death of his first wife, we may rule out the possibility that she returned with the intention of becoming his wife. Her second and third journeys to England were perhaps more likely to have been excursions from an Australian base, but – even so – they seem extraordinary. None of the six later voyages could have been anything like as uncomfortable and degrading as the first, on the Lady Penrhyn, but it is still remarkable that she could have wished to spend something like four years of her life tossing on the oceans in tiny sailing vessels.

We can dismiss two Hollywood-style hypotheses. It is highly unlikely that she sailed the seas by disguising herself in a male clothing in order to heave away and haul away as a sailor. She had successfully impersonated a man for a few hours in a gloomy and smoky English inn. It would have been impossible to have carried off such a deception for months on end in the confined space of a ship. It is also hard to believe that she returned to England to track down concealed proceeds of her career in crime. It was true that around £300 of the money stolen from Wigglesworth was never recovered, but much of this was probably in the form of bills of exchange, or other traceable forms of monetised documentation. This loot was probably destroyed around the time of her arrest in an attempt to avoid incrimination. Any attempt to turn it into cash decades later would certainly have aroused suspicion.

So how and why did Frances Davis travel twice more across the world – and back? Perhaps she became the partner of some unknown sea captain. There is no evidence that she went into business on her own behalf: she was described in 1823 as a housekeeper. Even if she had become a merchant or an innkeeper, by the early nineteenth century there were established trade networks with Britain, and she would hardly have needed to make personal visits to secure supplies. Even the pioneer large-scale pastoralists John Macarthur and Samuel Marsden made the global voyage very sparingly: Macarthur twice, Marsden once.

By the time of her death, in November 1828, there was a certain cachet associated with having arrived on the First Fleet forty years earlier, and the fact was recorded on her headstone. Her age was given as 64 years, pointing to her having been born in 1764.[56] More than twenty years later, her friend Mary Marshall was buried in the same grave. With nineteenth-century men, the sharing of the same grave is sometimes assumed to hint at a homosexual attachment.[57] However, there is really no reason to speculate that this might indicate that Frances Davis was bisexual. By the mid-nineteenth century, the Devonshire Street cemetery represented a scarce patch of cemetery real estate in downtown Sydney. The burial place of Martin Mintz is not known, but the headstone to Frances Davis seems to imply that she was the only interment in the plot. For Mary Marshall, who was possibly her heir and executor, it would have made sense to provide for the use of the same grave when her own time came. Indeed, in the early twentieth century, the Devonshire Street cemetery became the site of Sydney's Central Railway Station. The remains of Frances Davis were moved to the Eastern Suburbs, where she is now commemorated as part of a First Fleet memorial.[58]

Frances Davis: rounding off the story It would be pleasant to conclude this exploration with a brief picture intended to place Frances Davis in sharp historical focus. Unfortunately, in many respects she remains an elusive figure. Even the recovery of her most notable exploit, her daring theft at the Three Rabbits, poses unsolvable questions. Should her disguise in male attire be interpreted as evidence of bisexuality, or was she simply a very effective actor? Did she operate alone, or was she – as was confidently asserted at the time – part of a gang? Did her determined refusal to reveal details of the crime reflect a steely gamble that the justice system would not actually hang an attractive young woman, or was she intimidated by criminal associates? Above all, who was she, where did she come from, who were her family? One negative point has been established: she did not hail from the Essex parish of Little Ilford, as stated by standard reference sources. Had she been a native of the parish, it would have been unthinkable to have attempted to stage such an impersonation on her own doorstep. But this takes us no closer to identifying her, except as a Londoner living on her wits, hardly a very specific classification in a pulsating metropolis of a million people. Her surname can be either English or Welsh. In the eighteenth century, a long-distance Welsh cattle-droving trade helped supply the capital, but anyone connected to the London underworld could have easily discovered that moneyed ranchers frequented the Three Rabbits. In any case, Frances Davis chose to pass herself off as a horse-dealer.[59]

If tracing a background for Frances Davis seems impossible, discerning her in any historical foreground is hardly easier. Throughout the six years between September 1785 and November 1791, it is possible to combine admittedly sketchy official records with more personal chronicles and diaries to produce some account of her journey from Little Ilford to the south Pacific. We can bring to life, sometimes in vivid cameos, the voyage of the Lady Penrhyn, those early days at Sydney Cove, the Sirius stinking of vomit, the threats of sadism and starvation on Norfolk Island. Yet, for the most part, Frances Davis remains an unidentified face in the crowd, perhaps trying to close her eyes as she was forced to witness hangings, desperately blocking from her memory that terrifying moment in the Chelmsford courtroom when Sir William Ashhurst had reached for his black cap and pronounced that she too must die on the gallows.

The predominant impression must be that Frances Davis took care to keep out of trouble, although in the absence of punishment registers, we cannot be sure. In any case, it is impossible fully to plumb the horrors of her experience of the convict existence. To have endured fourteen years of transportation suggests that she was above all a survivor, somebody who would go on to two marriages and undertake three return journeys between New South Wales and the land of her birth.

She died on 11 November 1828, and was buried under her (second) married name, Frances Mintz. There were no children. Somehow it seems appropriate that the Devonshire Street cemetery did not prove to be the final resting place for this rootless, semi-nomadic woman whose global mileage rivalled that achieved by Captain Cook. In fact, the Frances Davis story ends in an honoured memorial to Australia's pioneers just half a kilometre from Botany Bay, whose shores she first saw when the Lady Penrhyn anchored in January 1788.

In conclusion, the other participants in the Little Ilford drama on that summer night merit a brief word. The inn itself, the Three Rabbits, survived the coming of the railway in 1839, which considerably reduced main road travel. Sometime around 1900, the Rabbits Tavern – as it was called in 1882 – was demolished, to be replaced on an adjoining site by a new Three Rabbits, a street corner public house built by a brewery in the Edwardian gin-palace style. "The original house was a much more modest building," commented a local historian in 1919.[60] The pub ceased trading around the year 2000. Its two upper storeys became apartments, while the ground floor bars were converted into a pharmacy, which itself closed in 2020.[61] There is nothing here that might assist even the most imaginative investigator in conjuring up the memory of Frances Davis smoking her pipe and stalking her victim.

John Wigglesworth carried on in the cattle business, but not for long. Of course, we should remember that in the eighteenth century, death struck at random and came in many guises. Nonetheless, it is difficult not to believe that the robbery at the Three Rabbits hastened him to the grave. Around £300 (equivalent to £50,000 or $A80,000 in today's money) of the loot stolen by Frances Davis was never recovered. The stress of the theft, the notoriety of the case and (no doubt, and however unfairly) the humiliation of being duped by a manipulative young woman – all these would have combined to break anybody's health. All we can say is that John Wigglesworth died on 14 May 1788, three months after Frances Davis arrived in Australia. He was 51.[62] Even in the romantic world of Australia's First Fleet, there was no such thing as a victimless crime.

Tailpiece (April 2021): In 1803, British newspapers (e.g. Star [London], 9 April; Aberdeen Journal, 20 April) carried a paragraph about "Hannah" Davis, "convicted some years since at the Essex Assizes for robbing a drover of £1200 at the Three Rabbits, at Ilford, by taking his clothes from under his pillow". This obviously referred to Frances Davis, and shows that her criminal exploit was well remembered seventeen years after her trial. The report stated that she was "now the principal farmer at Botany Bay", adding that "she continues as a single woman, notwithstanding the celebrity of her charms, and her being the first female convict landed in that New World." The report could hardly have originated in New South Wales, since there was no truth in the claim that she was the colony's leading farmer. Male ex-convicts were allocated small holdings of land, but there seems to be no record of any such grant to Frances Davis. It seems likely that she had returned to England by this time, and was either the focus of glamorous speculation or – sadly, more likely – spinning stories about herself, perhaps to con gullible investors into financing her alleged colonial estate. If the latter, then she was probably planning to return to New South Wales, if only to escape those she planned to defraud. Her impersonation of a horse dealer at the Three Rabbits indicates skills at role playing. The fact that the man she married in 1811, Martin Mintz, had tried farming on the Hawkesbury may also suggest that she had been assigned to work on the land during the 1790s. As noted above, women on Norfolk Island were employed in garden and field work. Perhaps the press reports encouraged her departure. I am grateful to Mark Gorman for drawing this report to my attention.

The Three Rabbits in 1880, a few years before it was demolished and replaced by a public house of the same name, on a site slightly to the right of this picture. It does not seem that the inn offered much sleeping accommodation. The upstairs windows had presumably been blocked to reduce liability to the Windows Tax, although this had been repealed in 1851.

It is unlikely that this contemporary sketch of Frances Davis resembled her in any way. J.Ashton, Chap-books of the Eighteenth Century (London, 1882), 451.

Sensational pamphlets about the life of Frances Davis were prepared for sale as souvenirs at her expected public execution. The more ghoulish entrepreneurs may have been disappointed by her reprieve for transportation. They could, however, take comfort from the reflection that they had not wasted much money on art-work. Ashton, Chap-books of the Eighteenth Century, 449.

For another First Fleet passenger on the Lady Penrhyn, see "James Smith, eccentric tourist on Australia's First Fleet: a tentative identification"

https://www.gedmartin.net/martinalia-mainmenu-3/330-james-smith-eccentric-tourist-on-australia-s-first-fleet.

ENDNOTES. Websites were consulted in January and February 2021. My thanks to Professor Peter Stanley for his help in this project.

[1] J. Cobley, Crimes of the First Fleet Convicts (Sydney, 1982, cf. 1st ed. 1970), 71-2; M. Gillen, The Founders of Australia: a Biographical Dictionary of the First Fleet (Sydney, 1989), 97. Frances Davis was the subject of several pamphlet-length biographies, which called her "Fanny Davies". There is little reason to believe that these represented anything but publishers' attempts to cash in on her notoriety by supplying a largely fictitious background. Thus one acccount stated that she was suborned by a brothel-keeper into prostitution at the age of fourteen. Another gave an entirely different story, portraying her as the manipulative mistress of a doting aristocrat. Chronologies are unreliable. One account described her as an experienced thief skilled in sexual exploitation who later engaged in large-scale thefts during the Gordon Riots: these occurred in 1780, when Frances Davis could only have been in her mid-teens. J. Peakman, Amatory Pleasures: Explorations in Eighteenth-Century Sexual Culture (London, 2016), 70-1; An Authentic Narrative of the Most Remarkable Adventures, and Curious Intrigues, Exhibited in the Life of Miss Fanny Davies, the Celebrated Modern Amazon ... (London, 1786).

[2] G. Martin, ed., The Founding of Australia: the Argument about Australia's Origins (Sydney, 198, corrected reprint, cf. 1st ed., 1978)

[3] Victoria County History of Essex, vi (1973), 163-74; A. Stokes, East Ham: from Village to Corporate Town (Stratford, [1919]), 22-30. There is still a Little Ilford Lane and the parish church survives: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1190948.

[4] T. Wright, The History and Topography of the County of Essex ... (2 vols, London, 1836), ii, 501; N. Pevsner, The Buildings of England: Essex (Harmondsworth, 1954), 150. Perhaps Little Ilford church owed its survival to the affection it inspired: in 1650 an official enquiry had recommended its demolition, and the partition of the parish between two neighbours. H. Smith, The Ecclesiastical History of Essex... (Colchester, n.d.), 251.

[5] D. Lysons, The Environs of London: being an Historical Account of the Towns, Villages, and Hamlets, within Twelve Miles of that Capital…, iv (London, 1792), 156.

[6] The 1821 census counted 97 people in the parish of Little Ilford.

[7] Lysons, The Environs of London, iv, 157.

[8] The quotation appears on page 15 of the undated Paris edition.

[9] Most of the story that follows is based upon reports in Chelmsford Chronicle, 9 September 1785, 17 March 1786; Northampton Mercury, 11 March; Leeds Intelligencer, 14 March; Hereford Journal, 16 March 1786. An Authentic Narrative of the Most Remarkable Adventures, and Curious Intrigues, Exhibited in the Life of Miss Fanny Davies, the Celebrated Modern Amazon, 29, called him "Wrigglesworth". The error does not inspire confidence in the account.

[10] John "Wiglesworth" is described as an innholder of Gosfield in his Will, mentioned on the Essex Record Office website, Seax. The one-g spelling appears to have been the one he used, but I have retained the double-g form given in press reports.

[11] Gosfield Hall and park are shown on Chapman and André's Essex atlas of 1777: https://map-of-essex.uk/.

[12] Had he travelled by stagecoach, he would almost certainly have gone straight through to London, and not stopped six miles short. The Three Rabbits was not a major coaching inn.

[13] S. Wood, A History of London (London, 1998), 377; F. Sheppard, London: a History (Oxford, 1998), 216. An attempt by Pitt's government to establish a London-wide police force in 1785 failed because it allegedly infringed the autonomy of the City. The claim in An Authentic Narrative (30) that Frances Davis was armed with a pistol when she pilfered Wigglesworth's bedroom seems unlikely. It was not mentioned at her trial.

[14] William Ashhurst was a 61 year-old judge, noted for the clarity of his interpretations of the law. He is best remembered for his statement in 1792: "There is no nation in the world that can boast of a more perfect system of government than that under which we live". D. Hay, "Ashhurst, Sir William Henry (1725–1807)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, supplemented by the entry by J. Macdonell in Dictionary of National Biography, ii. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography has settled on the double-H spelling: earlier sources generally preferred "Ashurst". The story in An Authentic Narrative (30) that Frances Davies used her stolen loot to support a life of "intemperance" in Chelmsford Gaol while awaiting trial seems unlikely, as is the detail that she kept three rabbits as pets in her cell.

[15] Hay in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

[16] P.G. Fidlon and R.J. Ryan, eds, The Journal of Arthur Bowes Smyth: Surgeon, Lady Penrhyn 1787-1789 (Sydney, 1979), cited as JABS. At the time, the author was known as Bowes. See also N. Cama, "Lady Penrhyn", https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/lady_penrhyn.

[17] https://sydneylivingmuseums.com.au/stories/first-fleet-ships/lady-penrhyn. The Ben Woollacott, which operates the Woolwich Ferry on the Thames, is 62 metres long, with a 19-metre beam. The Sydney Harbour ferries from Circular Quay to Manly, phased out in 2020, were 70 metres in length.

[18] So states Wikipedia, quoting a newspaper source for May 1786: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lady_Penrhyn_(1786_ship).

[19]I have tentatively identified the mystery passenger in https://www.gedmartin.net/martinalia-mainmenu-3/330-james-smith-eccentric-tourist-on-australia-s-first-fleet.

[20] The horses arrived at Sydney Cove "in excellent condition", but much of the livestock died on the voyage, JABS, 66.

[21] Evan Nepean, the Under-Secretary at the Home Office, thought it best to transport all the female convicts on the Lady Penrhyn, "tho' they might be a little crowded", rather than have male and female criminals on the same ships: this did not happen. Phillip complained that the number of women and children loaded aboard exceeded the agreed maximum of 102, and that in any case, the ship should only carry two-thirds of that number. Historical Records of New South Wales, i (2), 34, 77.

[22] The comment was contemporary, having been published in 1785 by James Boswell in The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides with Samuel Johnson.

[23] Phillip split the Fleet after Cape Town, sending the fastest vessels on ahead.

[24] JABS, 55. The storm had probably been funnelled through the Bass Strait, which was not then known to European mariners.

[25] JABS, 25, 43, 46. Jane Parkinson had been transferred from another transport, the Friendship, at Cape Town, to be placed under the care of Bowes during the last stages of the disease, an effective device to spread the risk of infection more widely. Bowes does not mention her burial, which may have been delayed to permit a post-mortem examination. A third convict, Ann Wright, had died on 4 April 1787, while the Lady Penrhyn was anchored off Portsmouth. The master, Captain Sever, noted that the crew "committed the body to the Deep with the usual ceremony." JABS, 174 (Appendix 1).

[26] JABS, 48.

[27] JABS, 11, 13.

[28] G.F.J. Bergman, "Johnston, Esther (1767-1846)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, ii, (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/johnston-esther-2276). Bowes did not mention the relationship in his journal, and omitted mention of Esther's daughter (by a previous partner), Rosanna Julian, born on board ship before the Fleet sailed.

[29] Historical Records of New South Wales, i (2), 58 (18 March 1786).

[30] JABS, 66-7. The clothes were refused by Ann Smith, a woman of about 30, who had been a repeat offender at London's Old Bailey, and had a poor disciplinary record on board. In June 1788, she was charged with insolence towards James Smith, the Lady Penrhyn's eccentric passenger, acting as convict supervisor. Told to extinguish her fire at night, she replied that she would do so if he went to the Governor to get her a pair shoes. She then added that "although on ship she took him for a gentleman, she now found quite the contrary." Ann Smith apologised, explaining that "she would not have spoken to him in that fashion had she not known him on the ship, and thought she might take such a liberty." She was sentenced to be flogged, a punishment that Phillip quashed. Cobley, Crimes of the First Fleet Convicts, 250-1; J. Cobley, Sydney Cove 1788 (London, 1962), 165. Another woman, Mary Davies, in her mid-20s, escaped serious injury despite falling head first down a gangway because she was "well defended by false hair" – apparently some form of wig. It seems remarkable that a convicted felon could wear such an elaborate fashion accessory. JABS, 49.

[31] JABS, 48.

[32] JABS, 48; J. Hunter (J. Bach, ed.), An Historical Journal of Events at Sydney and at Sea (Sydney, 1968), 6-7.

[33] Mary Marshall was a witness of the wedding of Frances Davis in 1808. There were two women called Mary Marshall on the Lady Penrhyn, but Gillen, The Founders of Australia, 97, identified the older of them as the friend of Frances Davis.

[34] Cobley, Sydney Cove 1788, 58-9, 87-8.

[35] Historical Records of New South Wales, ii, 746-7. The letter was partly printed in Stamford Mercury, 5 June 1789. The language is strikingly modern. See R. Teale, Colonial Eve … (Melbourne, 1978), 8, for an extract.

[36] H. Heney, Australia's Founding Mothers (Melbourne, 1978), 63-4.

[37] Heney, Australia's Founding Mothers, 63. Rebekah Allen was entrusted to Frances Davis on 24 October 1789, and died on 1 February 1790.

[38] Gillen, The Founders of Australia, 97.

[39] JABS, 65.

[40] Bergman, "Johnston, Esther (1767-1846)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, ii (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/johnston-esther-2276).

[41] W. Tench (L.F. Fitzhardinge, ed.), Sydney's First Four Years … (Sydney, 1979, cf 1st ed. as Tench, A Narrative… [1789] and A Complete Account… [1793]), 163. Tench was one of the smarter officers.

[42] Historical Records of Australia, series 1, i, 166, 204.

[43] P.G. Fidlon and R.J. Ryan, eds, The Journal and Letters of Lt. Ralph Clark 1787-1792 (Sydney, 1981), cited as Clark. Clark did not mention Frances Davis by name.

[44] Clark, 117. It will be apparent that orthography was not one of Clark's skills. I have omitted the intrusive [sic] but note here that he spelt "enough" as "a nuff" and "us" as "use".

[45] Clark, 119.

[46] Clark, 132.

[47] A. Summers, Damned Whores and God's Police... (Ringwood, Vic., 1975). The tradition that Clark so greeted the arrival of the Lady Juliana in Sydney harbour seems unreliable. The ship arrived in June 1790, when he was on Norfolk Island. Clark did describe the women of Norfolk Island as damned bitches, carefully laundering the term in his journal: "they make me Curs and Swer my Soul out". Clark, 178.

[48] Clark, 137, 163, 169-71, 185-6. I have not traced the phrase "comical cuck", although its general meaning seems clear enough from the context. "Cuck" was an abbreviated term for "cuckold", a man whose wife was unfaithful, and its application here to female anatomy is unexpected. Clark generally used dashes for improper terms, so a misreading seems unlikely.

[49] Calculated from Clark, 130-220, esp. 197, 178.

[50] She returned to Sydney on board the Kitty: https://peopleaustralia.anu.edu.au/biography/mintz-frances-29821/text36914.

[51] The best source for her later years is Cathy Dunn, "Frances Davis, Convict, Lady Penrhyn 1788," in the HMS Sirius website, https://hmssirius.com.au/frances-davis-convict-lady-penrhyn-1788/. Unless separately referenced, this is the source used below.

[52] https://peopleaustralia.anu.edu.au/biography/mintz-frances-29821/text36914.

[53] The wedding took place at St Philip's church in Sydney, which owed its dedication to the surname of the colony's first governor.

[54] Sydney Gazette, 31 July 1813.

[55] Sydney Gazette, 18 September 1823. Another useful website, https://convictrecords.com.au/convicts/davis/frances/134607, appears to indicate that Frances Davis was in New South Wales at the time of the 1825 muster.

[56] This conflicts with the reports in 1785 that she was 18, which suggested birth in 1767. Unfortunately the Sydney Gazette does not survive for November 1828.

[57] The theory has been persuasively rejected in the case of John Henry Newman.

[58] The memorial was inaugurated in 2016 as part of the Pioneer Memorial Park in the Sydney suburb of Matraville: http://fffsouthernhighlands.org.au/?page_id=1259.

[59] Frances Davis appears to have been recorded just once (on the occasion of her wedding in 1811) as "Davies", a form of the surname strongly associated with Wales.

[60] Stokes, East Ham: from Village to Corporate Town, 28-9. For the picture of the original Three Rabbits, from about 1880, ibid., facing page 26. It is reproduced at the end of the text.

[61] The Rabbits Tavern is referred to in 1882 in a document calendared by the Essex Record Office Seax website. For pictures and a list of landlords and residents, see https://pubwiki.co.uk/EssexPubs/Ilford/rabbits.shtml. I am grateful to Kevin Mansell for information on the pharmacy.

[62] This paragraph was revised on 16 February 2021, with the benefit of information generously supplied by the Reverend Rose Braisby, minister with responsibility for St Catherine's church, Gosfield, to whom I am most grateful. The Wigglesworth headstone is now difficult to decipher, but had been recorded previously. A document noted on the Essex Record Office Seax website shows that in 1788 his executors sued another trader for failing to pay for cattle purchased from the deceased "John Wiglesworth of Gosfield". The UK National Archives website indicates that probate was granted for the estate of John Wiglesworth, innkeeper of Gosfield Essex, on 6 June 1789.