A.C. Benson in images

The personality of Arthur Christopher Benson has been conjured and evoked through many thousands of words, his own as well as those of friends and biographers. Photographs have appeared in some of the books by or about him, but usually as silent adjuncts to the creativity of the text. This brief attempt at a photographic essay approaches Benson through the visual theme.

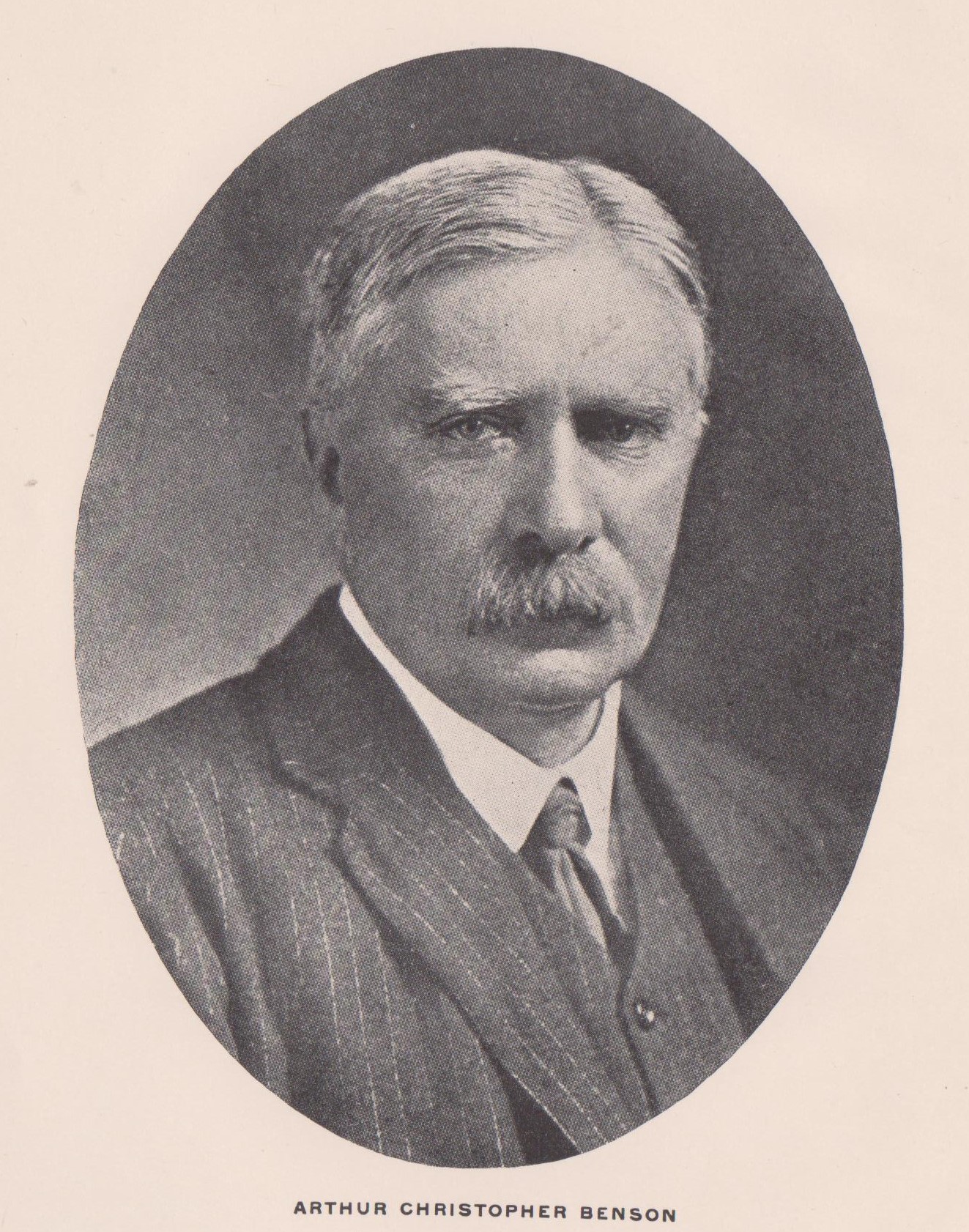

Notably, there are few portrait photographs designed to capture personality, and even in these Benson rarely confronted the camera full-face. In 1912, he admitted that he had become "an old buffer", adding: "In a taxi the other day I raised my eyes, and what a cross stout red corrugated old party looked at me crossly from the mirror!" It is a revealing, indeed a charming, admission – but it seems curious that even this self-revelation should have come through the small rear mirror of a taxicab. What did he see when he was shaving or dressing for dinner? Benson's apparent lack of interest in – or engagement with – his own apperance is all the more curious since he was himself an accomplished caricaturist. M.R. James recalled him whiling away time in academic committee meetings by producing "rather libellous likenesses of his colleagues", while another friend, Geoffrey Madan, preserved "a little sheaf of pen and pencil drawings, charateristically done at high speed; sometimes of old men seen for a moment in a club or a meeting". Sadly, these sketches seem to have been lost, and his skill forgotten. Perhaps the inscrutability that A.C. Benson displayed in most photographs reflected not simply a desire for self-protection, but an awareness that the visual record might unmask – or at least hint at – elements of himself that he preferred should remain hidden. It may be that he sought to protect himself from the penetrating gaze of others partly because he was not truly sure of his own inner identity. It is possible to distill a picture of Arthur Benson as he wished to be seen from his extensive writings, but it is equally clear that this cannot be the whole story. "Even his best friends had an uneasy feeling that something was lacking," wrote on early and puzzled editor, "though they found it hard to define exactly what the deficiency was." Perhaps the visual record may merit examination in its own terms, and not just as a decorative adjunct to biographical narrative.

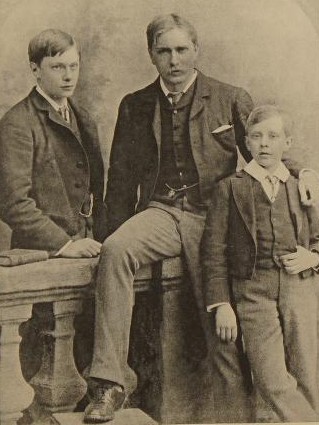

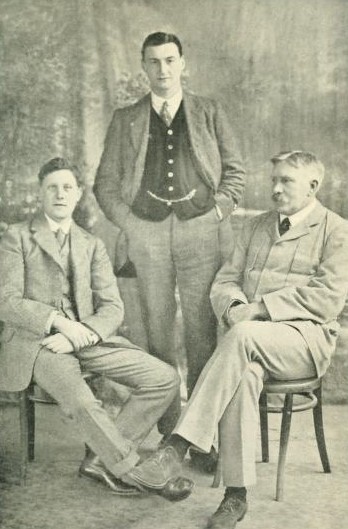

The Benson brothers, 1882 This posed photograph, taken in a London studio, dates from about the time their father, Edward White Benson ("EWB"), became Archbishop of Canterbury. In a sense, the photograph is haunted by the boys' elder brother, Martin White Benson, who had died four years earlier. Martin was a prodigy who was treated as an equal by his father, and EWB never recovered from his loss. Arthur Benson was conscious of his inability to live up to Martin's memory and take his place in their father's trust and esteem. When this photograph was taken, Benson was an undergraduate at King's College, Cambridge, where he experienced a major religious crisis and mental breakdown. He later described himself at this period of his life as "a big, shy schoolboy ... with no ideas about anything", a sense of awkwardness which the photograph captured. To his right (i.e. the left of the photograph) is his brother Fred (Edward Frederic), who would later become a popular author. The youngest of the brothers, Hugh (Robert Hugh), looks as if he is wriggling with impatience. In 1910, Arthur Benson wrote of him: "He is like a child, entirely absorbed in his own games."

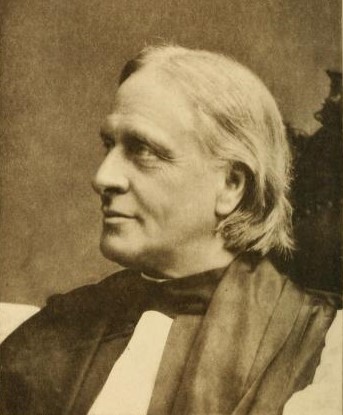

Edward White Benson, 1883 A.C. Benson's father at the time he became Archbishop of Canterbury. His appointment was a considerable promotion: he was one of the youngest and most recently appointed bishops, chosen to create a new diocese in remote Cornwall. Elsewhere, I have described the congestion of long-serving prelates in the Anglican Church as "see-blocking". "I mean to rule" was his comment on accepting the Primacy. The wider world saw the face of a strong personality who combined energy with spirituality. Few outside his family knew of his terrible bouts of depression, which at least two of his children would inherit, and the glacial absolutism with which he ruled his family. In later life, Arthur Benson would often dream about his father in situations where they behave as friends. Once, he found "EWB", dressed in his episcopal garb and playing with toys in a cupboard under a staircase – a magical location that would recur in children's fiction. "He loved me – I loved him not." Like many Victorians, Archbishop Benson could not find the way to express his feelings.

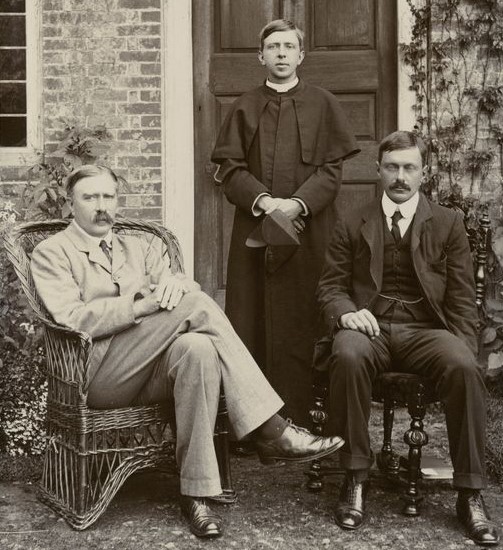

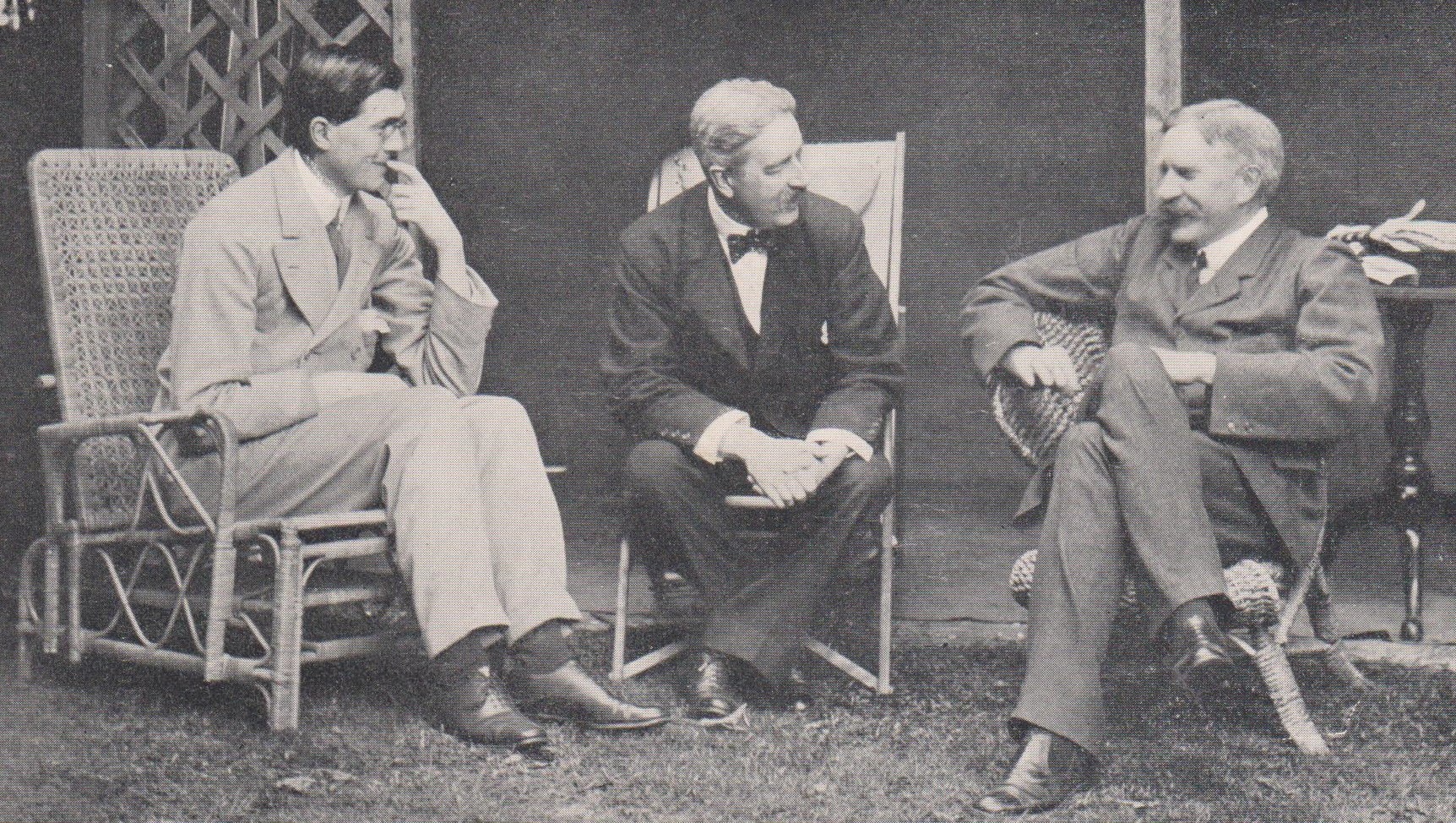

The Benson brothers, 1903/4 This picture has been dated to 1903, but the fact that Hugh is swinging a biretta points to 1904. Archbishop Benson had died in 1896, and each of the three brothers had redefined himself away from the image and personality of their intimidating father – Hugh most dramatically (and provocatively), by going over to Rome and becoming a Catholic priest. Fred was uncomfortable with his younger brother's inability to interact with people: "the human race (except in so far that they had souls to be saved), were playmates and companions, pleasant and interesting, but not individually absorbing." Hugh became a prominent apologist for his adopted Church: as Simon Goldhill wrote, he was "always arguing with the father he could never challenge alive". Fred Benson had become a popular novelist, chronicling the elite and effete world of the Bright Young Things. He enjoyed living a social butterfly life among the kind of people he wrote about, evading reality rather than challenging it head-on. Arthur was also well known as an author, but he preferred to look on from the margins of life: one of his most famous books was From a College Window, while Punch once facetiously announced that he was about to publish At a Safe Distance. In his student days, it had been widely assumed that he would seek ordination in the Church of England. Instead, he accepted an invitation to teach at his old school, Eton. The opportunity arose almost accidentally, but Benson attempted to turn his job as a schoolmaster into an alternative vocation. In 1903, he published a commentary on his aims and methods, with just that title, The Schoolmaster. However, that same year, he was glad to leave Eton and become co-editor of a three-volume selection of Queen Victoria's letters. Unlike Fred, he was not attracted to London and its literary scene. Rather – and perhaps surprisingly given his stressful years as an undergraduate – he chose to settle in Cambridge, a protected observation post that was close to the centre of events but slightly detached from them. An old family friend exclaimed of the three brothers in 1911: "You are not in the least like the children of Archbishops." That was the point.

The three seem awkward as they face the camera. Perhaps, as sometimes happened at Tremans, there had just been a family row, but Arthur habitually drew down the shutters as he stared down a lens. Perhaps curiously, this photograph became something more than a private family record. Ten years later, A.C. Benson noted that it had been "constantly reproduced". If the publicity it received was intended to hint that Arthur, Fred and Hugh hunted as a literary pack – provided complementary intellectual, superficial and spiritual interpretations of Life – then its use was misleading. In 1913, the brothers to be photographed again, "in a group exactly as we were taken ten years ago, in the same positions". I do not know if this sequel has survived.

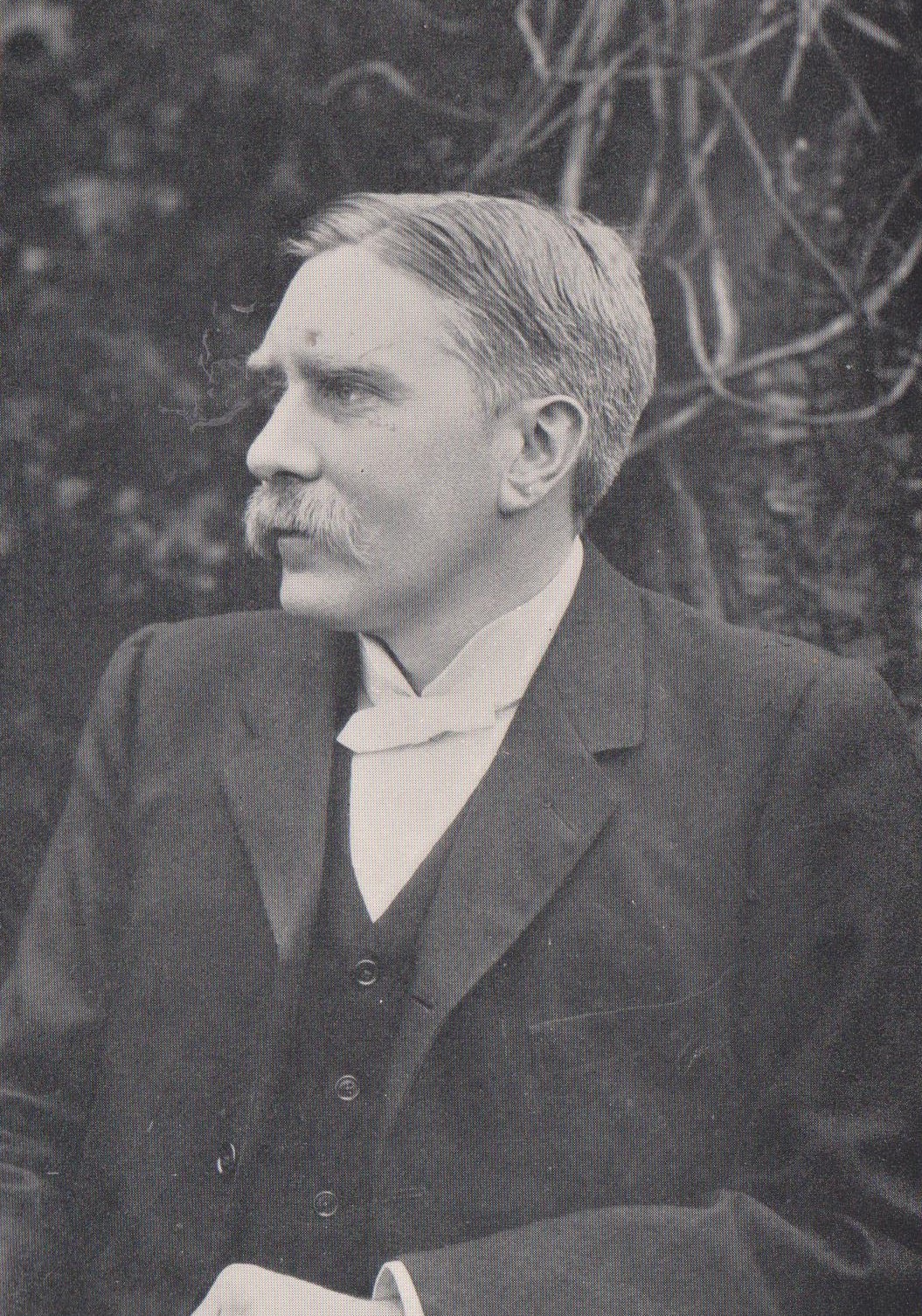

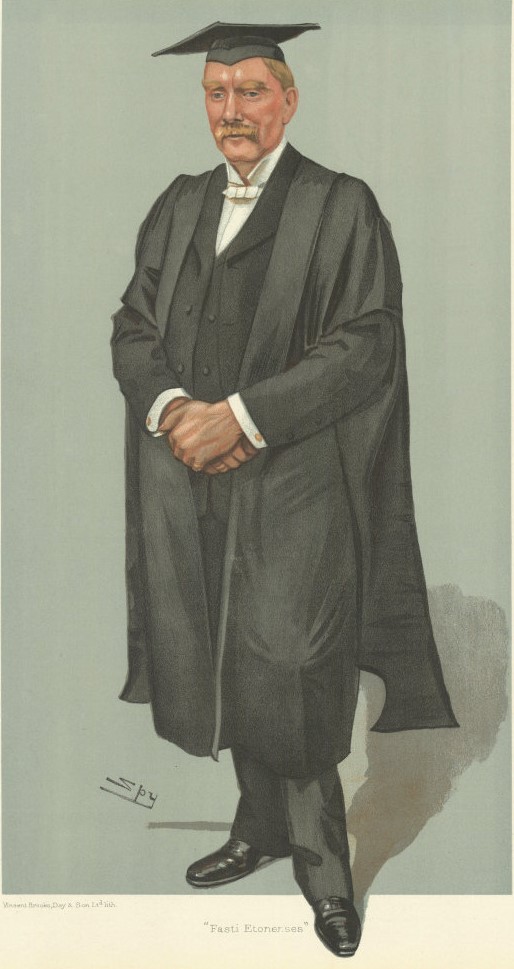

Benson as an Eton housemaster In 1893, when he was still in his early thirties, Benson became a housemaster at Eton. Edmond Warre, the headmaster who had invited him to teach, had recognised that the Eton curriculum, with its emphasis upon Latin and Greek, needed modernisation. Unfortunately, his way of doing this was to introduce new subjects without curtailing the emphasis upon the old. The result was a crushing workload for Eton staff, much of it involving the inculcation of rote learning and the correction of formal exercises. Housemasters carried an even heavier burden. In 1901, Benson defined his job as a combination of hotel manager, clergyman (which he was not – he meant counsellor), lecturer, coach (i.e. tutor to boys individually), policeman and athlete. A typical day would begin at 7.30 in the morning, with a lesson on New Testament Greek, and end after ten o'clock at night once he had chatted individually with the boys in his charge as they prepared for bed. He also carried an immense burden of writing, which included the production of a massive two-volume biography of his father. Fred Benson felt that his "had slid into the groove of a career", his success as an Eton housemaster making him "prosperous and popular... though from time to time his own cloud beset him, and out of it he would announce that the burden of his work was quite intolerable, and that he could not possibly stand it for another term." Fred did not take these jeremiads seriously: they "relieved his mind, and he buckled to with renewed energy and that amazing gift of getting through a task more quickly than anybody else could have done it, without the slightest loss of thoroughness, and he added to the work that was incident to his profession an immense literary activity of his own".

Yet A.C. Benson was more than ready to quit when he received the invitation to work on Queen Victoria's letters in 1903. Within ten years, "Benson's" had doubled in size. Although Benson, himself an energetic footballer in his student days, had become alienated by the cult of games, there was considerably more silverware on display in 1903. (He blamed Britain's initial military failures in the Boer War on the "deplorable barbarism" of the school's obsession with sport, an interesting inversion of the cliché that the battle of Waterloo had been won on the playing fields of Eton.) A few of the boys who passed through his hands became lifelong friends: Percy Lubbock, who published edited extracts from the Benson diaries, is third from the right in the back row of "Benson's" in 1893.

Benson at Eton, 1899 Wearing the uniform of an Eton master, Benson is pictured here looking thoughtfully into an unfocused distance, possibly reflecting on the meaning of Life and the purpose of Education. Perhaps it was taken for promotional purposes, in connection with the publication of his huge two-volume biography of his father. The photographer was A.H. Fry, who had a well-known studio in Brighton but also toured public schools and visited major events to provide portraits.

Benson by 'Spy', 1903 Eton masters were potentially national figures, if the nation was exclusively defined as people connected with the school. To mark his departure in 1903, the magazine Vanity Fair included him in its elegant cartoon series, the work of Leslie Ward ('Spy'). It is a stylised and slightly stilted interpretation, perhaps hinting that Benson was cautiously setting foot into uncharted territory. The caption, Fasti Etonenses, referred to a huge biographical dictionary that he had published in 1899. Burly in stature and vigorous in movement, Benson was noted for the "voluminousness, length, and silkiness" of his billowing MA gown, which made him look like a human galleon in full sail. As he strode along, "he had a peculiar trick of drawing the folds of it around him," like a Roman Senator in his toga. A Magdalene freshman recalled him as "tall and immense in his great gown, rubbing his clasped hands together", as he strode across First Court, with a "curious pad-footed prowling walk, as though he were threading a jungle". Since other colour representations from this period do not seem to have survived, it is impossible to say whether he had a ginger moustache. (If he did, the photographer who took the brothers at Tremans in 1903/4 must have applied a black brush.) The moustache would soon turn grey.

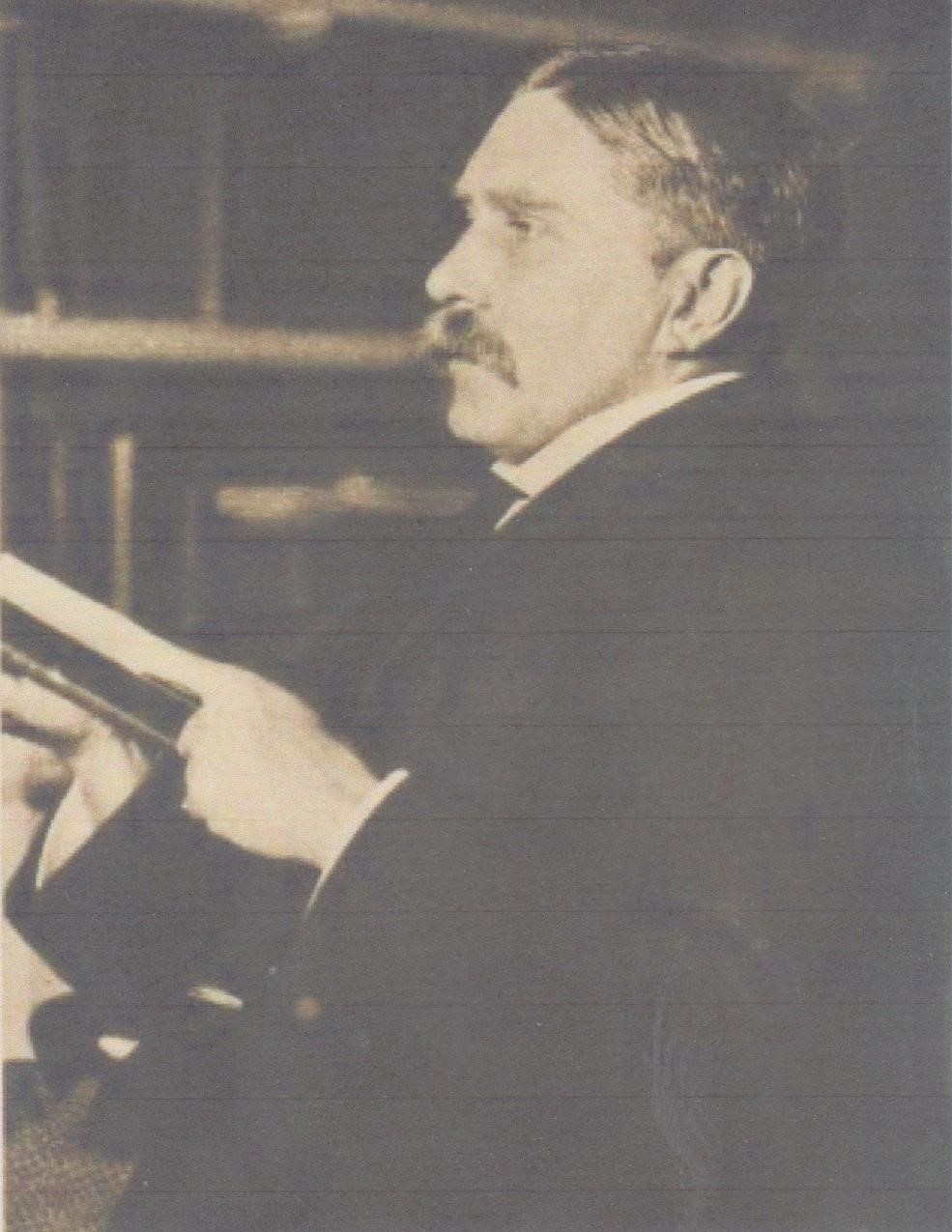

Benson as poet, 1906 This photograph, which accompanied a collected volume of poems, had probably been taken some years earlier. It seems oddly inappropriate. While he was unlikely to be portrayed like Swinburne or Oscar Wilde, Benson's cramped and defensive pose hardly invokes a lyrical muse. It would be difficult to guess from this picture that one of his most successful poems, The Phoenix, came to him in a dream: he confessed himself incapable of interpreting its imagery. In fact, he had largely given up writing poetry around 1900, although – perversely – his best-remembered lines are Land of Hope and Glory, which he wrote in 1902 – about a subject, the British Empire, for which he had no enthusiasm. His prose writing sometimes bore traces of his early commitment to florid versification: I have elsewhere described his use of "atonal" adverbs, such as the stream that flowed "hoarsely".

Benson with friends, 1906 Two years after becoming a Fellow of Magdalene, Benson took the lease of Hinton Hall at Haddenham, not so much a country house as a house in the Cambridgeshire countryside – "handsome and spacious" as a modern estate agent sale brochure recently described it. The following year, he slid into the first of the two breakdowns that would mark his time at Magdalene, later blaming the bleak and treeless Fens for the depression that had crept upon him. Haddenham is in fact located on a former island in the Fens, with open and – on a fine day – inspirational views of the vaulted sky towards Ely. Benson's real problem was that he simply could not live alone – although, in his case, "alone" included three faithful servants who accompanied him on his regular migrations to and from Cambridge. One of them, Jesse Hunting, was a skilled amateur photographer who captured this rare picture of Benson animated: he was chatting to two guests, Percy Lubbock and another favoured young man, Howard Sturgis.

All accounts agree that Benson himself was a delightful talker, but he possessed the still greater gift of being able to draw out his companions. His brother Fred, not always a flattering commentator, recalled Arthur as "the most stimulating but least dominating talker that I have ever met". "He talked with you", Percy Lubbock recalled, breathlessly greeting anecdotes with "I mustn't miss a word of this." "Few people, young or old, ever left Arthur Benson’s table without a modest consciousness of having been a little more delightful than usual." Many of these conversational athletes would then be derided, even crucified, in the pages of his diary.

This photograph is notable in being the only informal glimpse of A.C. Benson in the public domain. Fast film had become widely available in the early eighteen-nineties, along with cheaper portable cameras, making it possible to capture lively interpretations of individuals. Possibly other "snapshots" (the term came into common use at that time) have not survived, but it may be that Benson tolerated the camera only if he could defend his privacy by adopting an inscrutable glare in a formal setting.

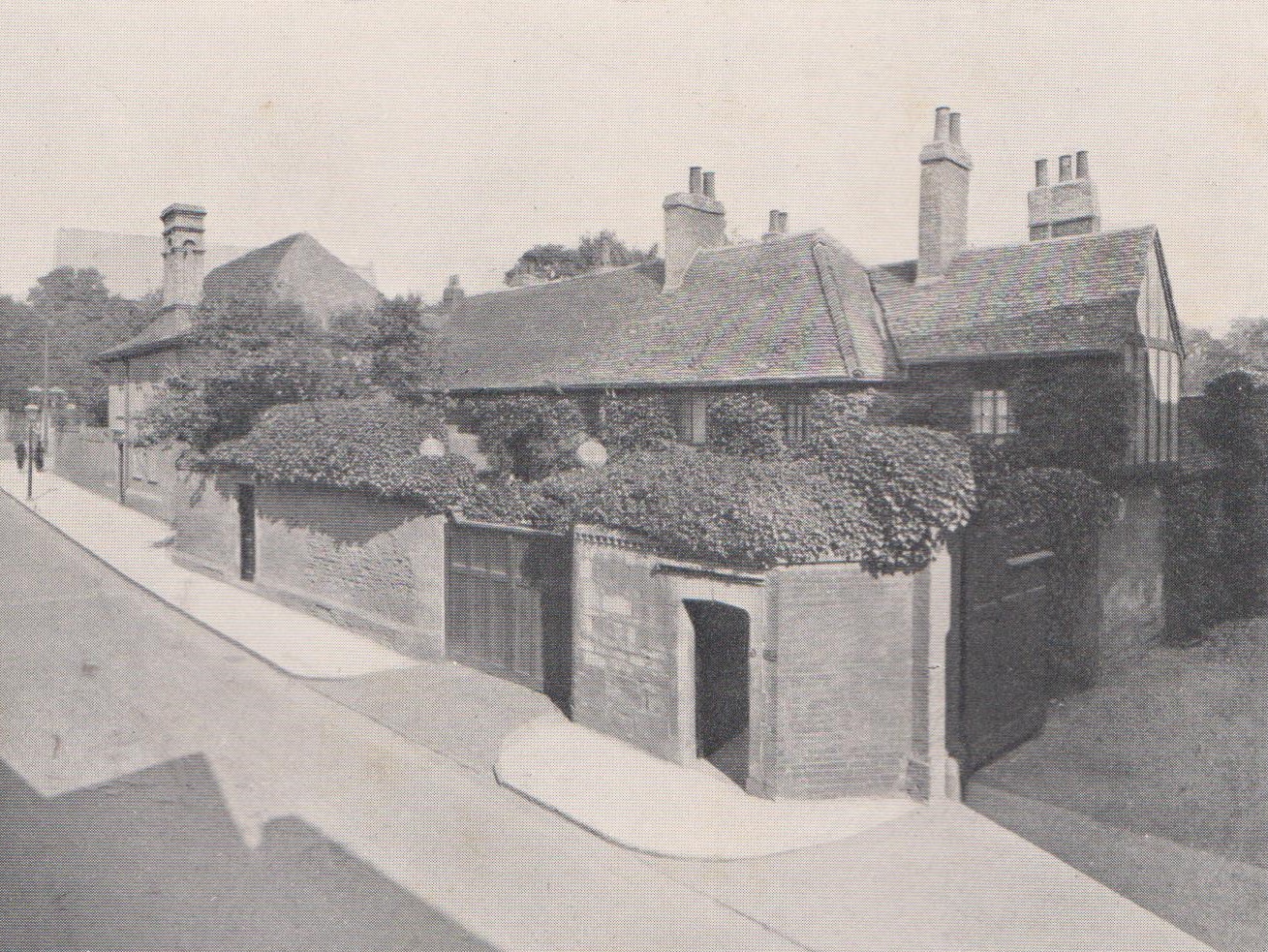

The Old Lodge, Magdalene College In 1908, as he recovered from his breakdown Benson abandoned country life and settled in the Old Lodge in Magdalene Street. It was a curious residence, not least in being – in effect – a private house within the confines of a Cambridge college – and a very small space at that. Until 1837, the Master of Magdalene had occupied rooms on the north side of First Court (the ground floor became the Parlour and Old Library). Since Masters could marry and produce large families, additional accommodation had been built at the rear. After the removal of the Master to a free-standing Lodge in its own grounds, the add-on apartments were remodelled into a house that was occupied for several decades by Professor Alfred Newton, who held the Chair of Zoology. Newton's death in 1907 opened the way for Benson to become the new tenant. Percy Lubbock viewed it as "an inconvenient and cheerless dwelling", with rooms that never knew sunlight, a building that was "shaken to its foundations every hour by the omnibus that thundered down the narrow street". (The traffic in Magdalene Street would get worse, and the buses certainly became more frequent.) But Benson called it "a stately little mansion" which he soon enlarged "in accordance with his highly eclectic taste". Most notably, at the north end he added "a great room like a college hall, with a gallery and a high-table". This is now a College meeting room known as Benson Hall. An external plaque ("ACB 1912") dates its completion. The photograph, which shows only one chimney, possibly dates from that time.

I confess that when I first saw Benson Hall, at a History Freshers' business meeting in 1964, I concluded that it must be the work of a megalomaniac, and I have intermittently probed its creator's personality ever since. His brother Fred commented that the whole contrivance of A.C. Benson's house was "as much an expression of himself as is the shell of an oyster", a revealing choice of a hard external metaphor. The key point about the Old Lodge was that it was physically separated from First Court by the original entrance drive to the Master's Lodge, enabling Benson to combine detachment with sociability. ("I live on the outside of things," he wrote in 1911, but he did not like to be too remote.) In 1926, the buildings were linked to the rest of the College and converted into student accommodation. Benson's study became a don's set, and new gates to the Master's Lodge were constructed to the north of the baronial hall.

Benson, Beth – and his mother Thus far the images defining Benson have come from a masculine world – Eton, Magdalene, his father, his brothers. "I am entirely a person of male friendships," he reflected on one occasion, while on another it occurred to him that "I like women the more they approximate to men". Yet even the greatest misogynist was born of woman, and Benson too had a mother. Mary (Minnie) Sidgwick came from an able family – her brother Henry Sidgwick was one of the most notable intellectual figures of nineteenth-century Cambridge – but widowhood and poverty had led her own mother to agree to – connive in – the curious courtship of Edward White Benson. EWB informed her that they were engaged when she was twelve and supervised an education suitable for her role as wife of a schoolmaster / clergyman. By the time of her marriage, at the age of eighteen – the term "groom" had more than meaning here – she had learned Latin but apparently knew nothing about sex, as may be deduced from an oblique but chilling account of the wedding night. She charmingly acted her role as EWB's hostess and (less efficiently) household manager, while also producing six children – and she seems also to have gradually ceased to fear her husband and learned to manage him. However, she was perplexed by parenthood and, for much of the time, simply opted out of relating to her children, preferring instead to engage in passionate female friendships. The Benson brood was reared by Elizabeth Cooper ("Beth"), Minnie's own childhood nurse who lived with the family until her death at the age of ninety: Benson felt that she was the only person he ever truly loved.

After EWB's death, Minnie retreated to Tremans, a rambling house in Sussex, which she shared with Lucy Tait, daughter of EWB's predecessor at Lambeth Palace. Queen Victoria thought it charming that the daughter of one Archbishop should be the companion of the widow of another, but Queen Victoria did not understand everything that went on in her dominions. Tremans was expensive to maintain, and the cost fell largely upon the two successful authors, Arthur and Fred. Hugh regarded himself as exempt from contributing on account of his priestly vocation, although he established a small oratory at Tremans in order to say Mass. Although A.C. Benson liked the house ("It is more my home than any place", he commented after making a return visit in 1924, six years after his mother's death), it does not seem that he felt entirely at ease there. (Fred, on the other hand, remembered his dramatic arrivals "bringing with him his motor-car and his benevolent despotism".) Indeed, Benson looks awkward in this group photograph taken at Tremans in 1911 as he stands behind the comfortable figure of his mother, who seems to take her lifestyle for granted. Next to her is the slight but cadaverous figure of Beth, who died shortly afterwards. Benson also had two sisters. Mary Eleanor (Nellie) bravely worked among the poor during an outbreak of diphtheria, and died of the disease in 1890, at the age of 27. The intelligent and questing Maggie (nobody called her Margaret) studied at Oxford and excavated a temple in Egypt, but was kept in polite servitude by ill health and her manipulative mother. She was frequently confrontational in dealing with her family, so much so that an exasperated Nellie once remarked that it would be a step forward if she could even build a relationship with a cat. (The Bensons were dog people and had no conception of the complexity of feline-human interaction.) Maggie suffered a violent mental breakdown in 1907: her death nine years later was a release. Feeling obliged to produce a memoir, Benson worked through her private papers, research that helped trigger the recurrence of his own illness. Viewing womanhood through the prism of his mother and his sisters, he could never quite trust in the idea of female friendship.

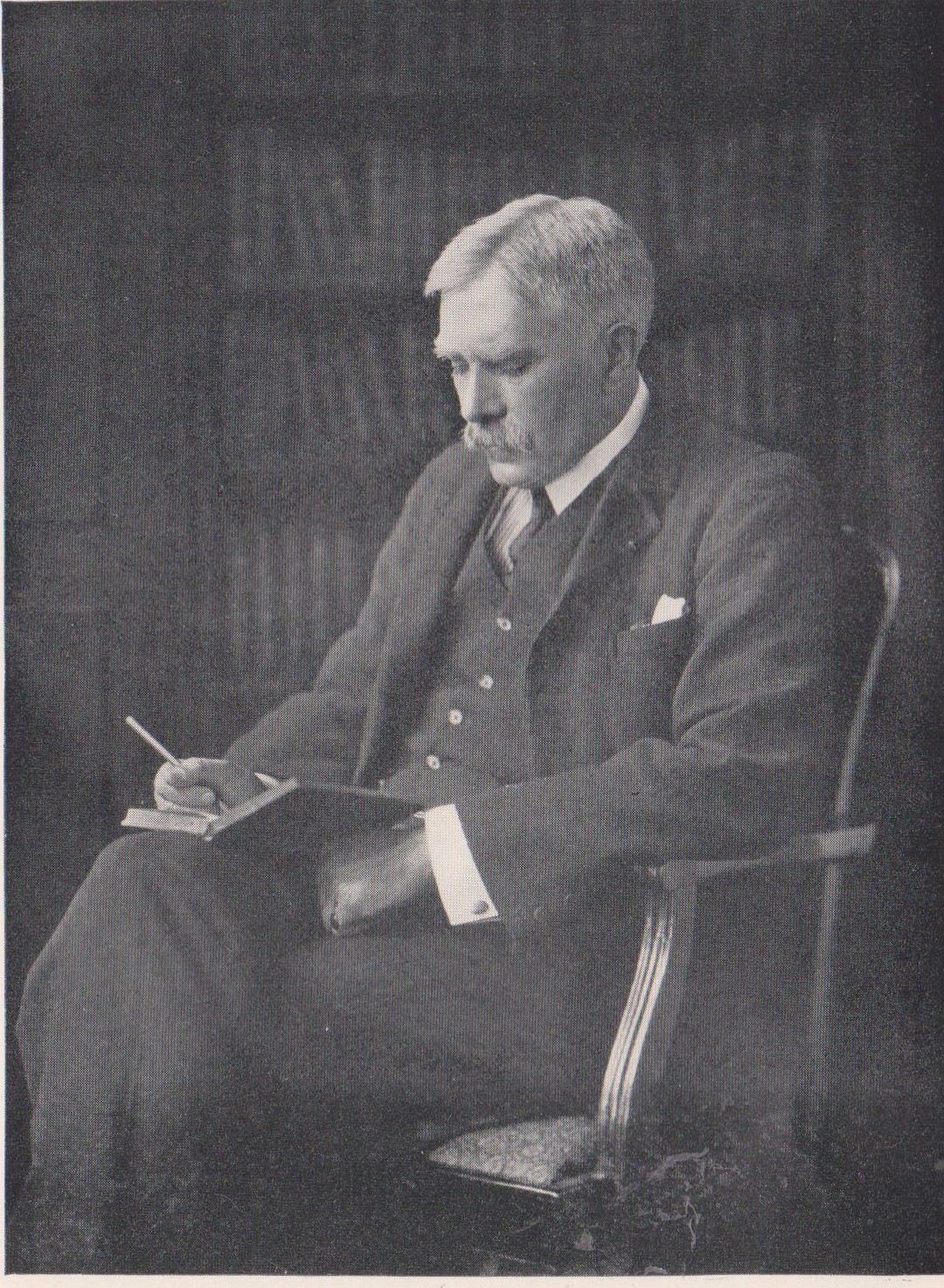

Benson pensive, 1911 It is hard to avoid the suspicion that this posed portrait, by the London photographer Carl Vandyk, was intended for the promotion of Benson's increasingly ethereal books about Life. He is holding a pencil and either writing in a notebook – perhaps his diary – or thoughtfully annotating a text. His heavy eyelids and head slightly inclined forward might suggest contemplation – or perhaps sleep. The plain fact was that the Benson of real life was not the Benson of popular adulation. His friends joked that "his books were all composed ... by somebody who slipped into the place of the man we knew". They professed to admire "how sociably he cultivated seclusion, how energetically he commended repose ... his books were less than ever the reflection of his life". They playfully insisted that "these easy-going mellifluous pages, with their rather faint and solemn discourse" could hardly be the work of "the masterful, combative, richly humoured man that we knew". In reply, he would doggedly insist that the author of his books, "the unworldly dreamer, the mild and placid recluse, was truly himself", while his day-to-day character, "that of a man who thoroughly enjoyed the business and bustle of the world, was ... mainly assumed for self-protection". Perhaps there was something to be said for this seemingly perverse defence of his authorial personality, for "he never really wrote at all ... he talked his books out on paper". His vast popular readership certainly believed in the nobility of his character. Women in particular responded to the book-Benson, and he received frequent offers of marriage. He felt sympathy for one volunteer bride. "Fancy her horror at finding a stout old buffer! I must send her my photograph."

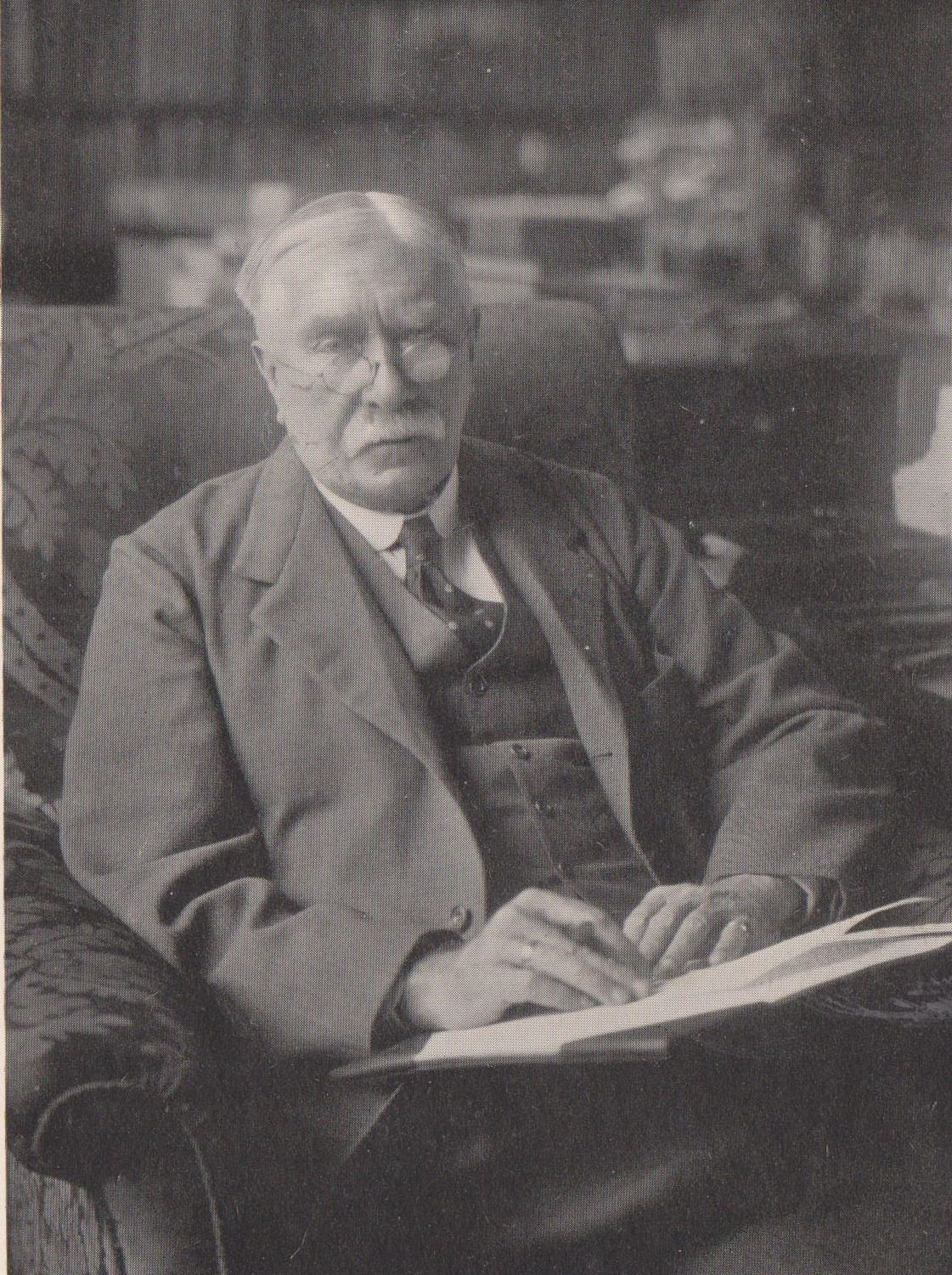

Benson in his early sixties "The visitor, on entering his crowded and book-lined little study, found him seated in an armchair by the window, a writing-board on his knees, hurling his letters as he finished them into the post-tray by his side." He spent every morning dealing with correspondence, often replying to enquiries from strangers with such empathy that they felt impelled to write to him again – and again. Friends estimated he dashed off between twenty-five and forty letters each day. At one o'clock he would host a luncheon party, sometimes with colleagues but nearly always to get to know Magdalene undergraduates, who were invited in twos and threes: one Term, he chalked up 104 of them. The guests would be tactfully evicted at two o'clock, to allow him to take regimented exercise, walking or cycling the byways of Cambridgeshire. Each expedition was precisely timed. "If the east wind blows and it begins to rain miserably, and you happen to be near home at half past three, still you must turn away and take a further round, or you will find yourself indoors before tea-time. If it is a perfect evening of summer, and the shadows are falling cool and fragrant between the hedges after the glaring day, still you must leave them and hurry home", for by half past four he had to be at work on his latest book. But, despite his disciplined regime, Cambridge life took its relentless toll. The relentless pressure to host luncheons, the daily duty of dining on High Tables, the cruel imperative to attend Feasts – all combined to leave their mark. By 1913, he weighed fourteen and a half stone (203 pounds or 93.1 kilos).

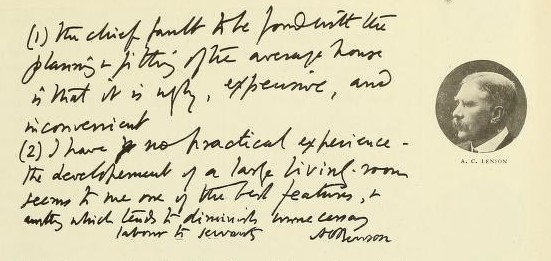

"We mustn't let people down!" In June 1925, Benson suffered the heart attack that led to his death. Two former students had written to request job references, and he asked his Magdalene colleague, A.S. Ramsey, to prepare the necessary testimonials, outlining what he wanted to have typed in his name. His comment, the last words Ramsey ever heard him utter, reflected his sense of obligation to the people who appealed to him, however little claim they might have upon his time and his generosity. I include one curious stray missive from the many thousands that he must have penned. In 1911, a construction company developed a garden suburb at Romford in Essex, which was given the invented name of Gidea Park. A sales fair was disguised as an exhibition of urban planning. Well-known personalities were invited to contribute their thoughts, which were incorporated into an elegant exhibition catalogue, conveying the impression that Gidea Park was endorsed by Arnold Bennett, Millicent Fawcett, Thomas Hardy, H.G. Wells and the Headmaster of Eton. The unwitting supporters were asked two questions – what was wrong with modern houses and what could be done to improve them? It is unlikely that A.C. Benson devoted much time to his replies – the average house was ugly and too expensive, builders should provide bigger living rooms and think of the workload of servants – but every letter, however trivial, transient or intrusive, was an addition to a burden of longhand correspondence. Despite his disclaimer, he was designing extensions to his Magdalene apartments, the Old Lodge, at about that time. These would include Benson Hall – perhaps the spacious "living room" that he had in mind?

A.C. Benson: seeking Paradise or evading Hell? After six years, Benson finally emerged from the prolonged depression that had overwhelmed him in 1917. The last two years of his life have been portrayed as, if not an Indian summer, at least a benign autumn in which he finally enjoyed an honoured position at the head of a lively and successful college. Amateur diagnoses should always be treated with considerable reservation, but if, as seems likely, Benson suffered from bipolar disorder, then the upswings must be regarded as forming as much a part of the affliction as the descents into the depths. Benson once wrote that he always seemed to be "on the edge of Paradise and never quite finding the way in". In 1980, David Newsome fashioned the title of his biography from that comment: On the Edge of Paradise. A. C. Benson: the Diarist. But in a thoughtful review essay, Ronald Hyam objected to this approach, insisting rather that Benson had established his base-camp on the edge of Hell.

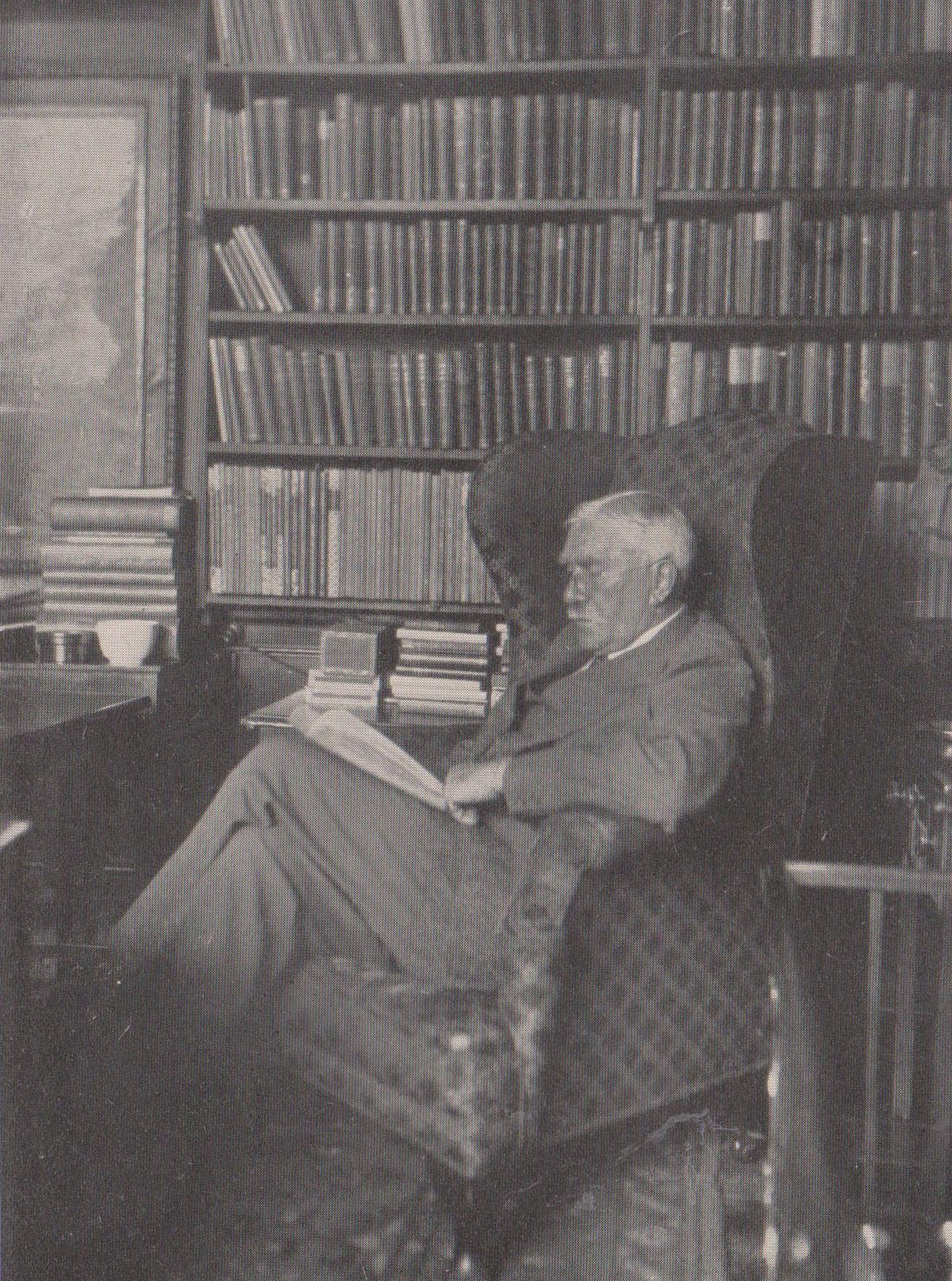

Two images from these final years illustrate these contrasting interpretations. The 1923 photograph above reflects the Paradise / serenity theme. Benson is shown reading in his study in the Old Lodge. He is seated in a high-backed armchair which embraces and encloses him, symbolically protecting him against the harsh world. (His headmaster, Edmond Warre, owned a similar piece of furniture, which he called Great Snorum.) This may well have been the armchair in which he suffered the heart attack that would prove fatal. Behind him the shelves rise above our line of vision, not simply lined with books but rather packed with leather-bound tomes that embody well-tested and reassuring truths about every aspect of Life.

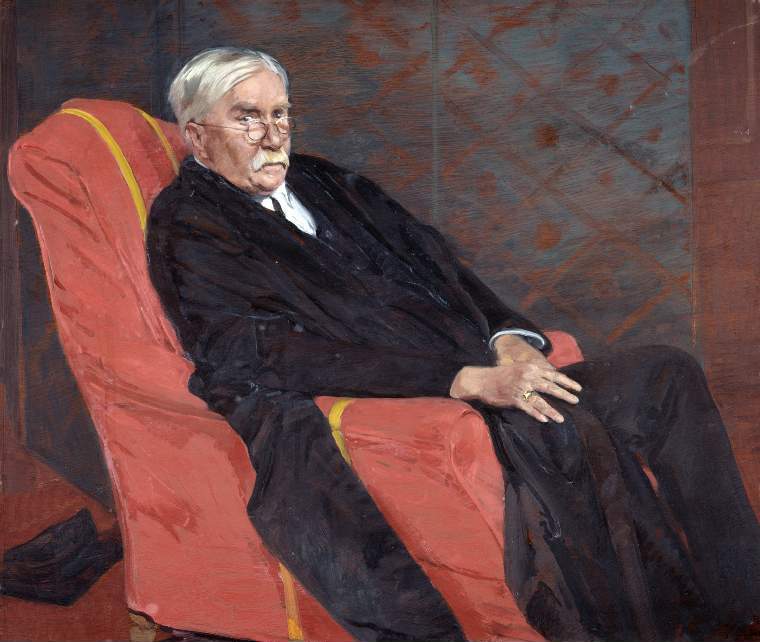

"A greedy, irritable rather bloated affair, but not unlike me" William Nicholson had made his first attempts to capture Benson on canvas in 1916, before the Master of Magdalene was engulfed in his prolonged final bout of misery. Sittings resumed in 1923, and it may be suspected that Nicholson's interpretation was affected by his knowledge of Benson's mental breakdown. Work began in Nicholson's London studio, where the sitter was placed in an armchair that somehow did not seem to fit him. Puzzlingly, he is wearing glasses, those same round, rimless spectacles through which had bleakly reacted to the intruding camera in the 1923 photograph. It seems that he only wore glasses for reading and writing, which suggests that we have once again disturbed him at work, although no books or papers can be seen. Elsewhere, I have called it a haunted and hunted portrayal. Has he perhaps just heard the news that George Mallory, one of his golden young men, has been lost on Everest? The gown suggests that he is about to take part in some academic ceremony: can he face a public performance after such a shock? As quoted above, Benson thought Nicholson's interpretation of him personally unflattering but visually accurate. "I am a stout bilious man, with a heavy jowl and red-rimmed eyes ... all the coarse and bored elements have come to the surface." He either did not recognise that Nicholson was hinting at sadness and madness, or could not bring himself to write those words. The portrait was gifted to the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, but it has been on loan to Magdalene since 2018.

Memories and Friends In 1924, Benson published one of his best books, a series of biographical sketches of people he had known at Eton and Cambridge. Just as he used his diary to re-fight (and win) the battles of daily life, so in Memories and Friends he drew a line under his fraught relationship with his old school, clothing its more eccentric personalities in a tolerant twilight glow. The author was illustrated in the frontispiece, and we are entitled to assume either that he selected the image himself or that his publishers chose one that they believed encapsulated his personality. It is unusual in being face-on, with no spectacles to form a barrier, half-defensive, half-designed to intimidate. We are led to Benson's eyes, which seem reproachful and regretful, even on the verge of tears. In no way do they provide windows into his soul. Perhaps the overwhelming emotion that emerges from the picture is the subject's own bewilderment. Looking back on his elder brother fifteen years after Benson's death, Fred concluded that "[t]he key to the inconsistencies of his strangely self-contradictory character was that he had a double personality, sharply divided with no conjecturable point of contrast between them." Percy Lubbock saw the dichotomy from a slightly different angle: "Arthur Benson talking to himself and Arthur Benson talking to another were two very different people, so different in many ways that the link between them might often be difficult to discern." Lubbock, who knew him as well as any of his contemporaries – so much so that their friendship was often strained –believed that Benson never penetrated his own enigma. "Introspective as he was often believed to be ... in fact he never knew himself well enough to record himself aright."

Bensonography In the year of his death, Benson was commemorated in a series of often insightful essays by friends, plus a venomous tailpiece by Edward Lyttelton, the intensely competitive headmaster of Eton (from 1905 to 1916), which tells more about its author than its subject. Arthur Christopher Benson by Some Friends was edited by Edward Ryle, a one-time pupil in his Eton house. (Benson was also Ryle's godfather and, as a boy at the school, had skivvied for Ryle's father as his fag: it was an inward-looking world.) One of the contributors was Percy Lubbock, who was also commissioned to work through the 180 volumes of A.C. Benson's diary (one of which he lost) to produce a digest that appeared in 1926 as The Diary of Arthur Christopher Benson. Lubbock somehow managed to shoehorn two nightmare nervous breakdowns and the carnage of a world war into a volume that still exudes a readable and restful Edwardian serenity. The diary was then sealed until the fiftieth anniversary of its creator's death.

In later life, both Arthur and Fred Benson produced books that began to roll back the veil on their parents' marriage. However, it was not until 1971 that Betty Askwith, in Two Victorian Families, revealed the horror of EWB's determination to fashion a twelve-year-old girl into his dream bride, an almost unbelievable tale of male chauvinist Pygmalion that would be more likely to lead to a prison sentence than a bishopric in modern times. Arthur left a typescript biography of his mother, Mary Benson: a Memoir, which was eventually published in 2010 by the E.F. Benson Society. The Introduction, by Gwen Watkins, cuts through the continuing evasions of a loyal son.

In Godliness and Good Learning (1961), David Newsome had described Martin Benson and movingly recreated his father's grief at his untimely death. Newsome was the obvious choice as the biographer who could build upon A.C. Benson's diaries when they became available in 1975. On the Edge of Paradise: A.C. Benson the Diarist (1980) is an impressive book, but it is also curiously opaque. Faced with five million words in which Benson reshaped the world around him and evasively wrestled with his own identity, Newsome evidently felt the need for an organising theme. He chose to docus upon Benson's unconsummated homosexuality, although his attraction to young men is never quite described in those terms. As a result, the biography supplies fascinating glimpses and sharp quotations, but somehow leaves much of Benson's life in obscurity – notably his work for Magdalene, which (after all) became the central project in his life. The agenda was cogently redefined by Ronald Hyam's incisive essay in the Cambridge Review (5 December 1980).

Unfortunately, Hyam's plea for a more open interpretation of the diary ("this superb document") remained unanswered for a quarter of a century. Simon Goldhill – like Benson himself, a classical scholar and a product of King's – quarried Benson's diary for his 2016 study, A Very Queer Family Indeed.... Boldly asserting the impossibility of biography ("the attempt to summon up a life in neatly chronological prose is bound to be an expression of its own failure"), he sought rather to chronicle the torments of the entire Benson clan. Although one might perceive a logical inconsistency in the approach – if a single life cannot be captured, how can we be confident of the accuracy of a batch? – but Goldhill powerfully drove his subjects from chapter to chapter, through challenge after challenge. Running through his confident text is the theme of the relationship between experiences and the words that may help to capture and express them. The Bensons lacked the vocabulary that might have enabled them to confront and comprehend themselves: Arthur, for instance, used term "homo-sexual" (which he hyphenated) just twice, and only at the very end of his life. Goldhill provided many previously unknown pungent quotations from the diary, although it was not usually his purpose to range much beyond his central theme. Curiously, although published by a major academic press, A Very Queer Family Indeed has no index, which makes it difficult to isolate A.C. Benson as an individual.

Can the camera lie: a Winterbotham's Tale? The Newsome / Goldhill emphasis upon Benson's sexuality is, of course, entirely valid, and has most certainly probed an area of his life that earlier commentators such as Percy Lubbock and Fred Benson had left intriguingly veiled. The risk that this approach may unwittingly distort the overall interpretation of Benson's activities has already been noted: Michael Ramsey paid tribute to "his thoughtful and careful kindness to young men who were not within his 'romantic orbit'." There is also a danger that the emphasis upon Benson and boy love may influence the way in which we view his participation in some group photographs. It is for that reason that I illustrate here a studio portrait that, frankly, does not justify inclusion on its artistic merits. It was taken in 1911, during a holiday at the picturesque Cotswold town of Burford, apparently the work of a local photographer. The frowsy curtained background and the jumble of booted feet underline the awkwardness of the composition. Benson looks away from the intrusive camera, and this may tempt a modern observer to assume that he was surreptitiously admiring Frank Salter, the young academic seated on the left whom he had recently imported from Trinity to teach History at Magdalene. However, this would be a misinterpretation of Benson's typically evasive attitude to photography. Indeed, Benson did cherish a romantic passion at the time, for the third figure in the portrait, a third-year undergraduate called Geoffrey Winterbotham, who looms behind the two Magdalene dons. To account for the young man's presence in the picture, which he used to illustrate his edition of the diary, Lubbock was obliged to describe their relationship, quoting Benson's view that Winterbotham was a "wholesome, handsome, natural creature ... a perfect companion, and I have never lived with any one in such peace and comfort". It was left to Newsome to reveal that Benson invested this brief friendship with much deeper emotion, although it was unfortunate that he converted the object of affection into "Winterbottom". It was a transient passion. As Benson recognised, Geoffrey Winterbotham had "nothing literary or precious about him". He left Magdalene in the summer of 1911 with a Third Class Honours degree in Classics and embarked upon a successful business career in Bombay, which eventually led to the scarce distinction of receiving a knighthood during the reign of Edward VIII. The lessons of the Burford triptych are simple. Not all photographs are very revealing, and posterity should beware of viewing images from the past through the prism of concerns that may excite the present.

In 2018, I set out to explore the myth – or was it the ghost? – of A.C. Benson that had seemed to hover over Magdalene College in my own student days. John Walsh, a History Fellow in the nineteen-fifties, had even wondered whether the institution was "a Bensonian construct: an attempt to embody the romantic vision set out from his From a College Window?" My enquiry, from the confines of my study in County Waterford, suffered from the same kind of limitation as Benson's own attempts to elucidate the universe from his rooms in Old Lodge. In my case, the constriction was all the greater since the major source, the diary, was available to me only through the snippets and extracts made by others. Yet I believe that I can report that I discovered much that seemed important but had somehow had not appeared in previous accounts. For instance, Benson's religious crisis and accompanying breakdown in 1882 had not been associated with its obvious trigger, a revivalist meeting harangued by the American evangelist Ira D. Sankey. Nor had its timing been placed in its equally patent context, the final illness of Archbishop Tait and the increasing probability that Benson's father would succeed him as Primate. Nobody seemed to have recalled the embarrassing sympathy that A.C. Benson expressed for the murderer Crippen, nor that he fervently believed in reincarnation (although perhaps not for Crippen), while the fact that he claimed (however absurdly) to be a socialist had most certainly been deleted from the Magdalene tradition. His opposition to forcing boys and undergraduates to study ancient Greek had indeed been noted, but not the scornful ferocity with which he savaged opponents in that controversy. In fact, he planned not merely to tinker with an essentially classical curriculum but rather to overturn it completely in favour of a modernist classroom agenda. Many other episodes in his career, such as his mental breakdowns and his pacifism in 1914, merit far deeper analysis than they have received in narrative biography.

I do not claim that my two-part essay, "A.C. Benson and Cambridge", answered many questions about him, but I do believe that my reconnaissance established the need for a wholly new biographical approach. The essays may be read at https://www.gedmartin.net/martinalia-mainmenu-3/284-benson1 and https://www.gedmartin.net/martinalia-mainmenu-3/288-a-c-benson-and-cambridge-2-1885-1925. At the time of writing (March 2024), there is a welcome prospect of a large step towards that endeavour, the publication of a new and extensive edition of the diary of A.C. Benson, edited by Eamon Duffy and Ronald Hyam. It will be jointly published by Magdalene College and Pallas Athenae Press, and is planned to appear shortly before the centenary of the diarist's death in 2025.

A final word on the images themselves, and how they have been used. A.C. Benson was so effective in painting word portraits of himself – however ethereally misleading they may have been – that there has perhaps seemed little room for the photographer or the artist to contribute. Percy Lubbock, himself a skilled wordsmith, made a sensitive choice of illustrations to add a dimension of reality to his edition of the diary, and even appealed to the snapshot of Benson entertaining at Hinton Hall in 1906 to demonstrate that he was far from taciturn as a host. The twenty photographs in Newsome's biography were used to convey the flavour of Benson's wider world (more specifically, late Victorian Eton and early twentieth-century Cambridge), and to illustrate the concept of boy beauty through some of its more elegant physical manifestations. Benson appears in fewer than half the pictures, sometimes merely glimpsed in a group, with only two photographs apparently chosen to enquire into his personality. Newsome did quote something of Benson's response to the 1924 Nicholson portrait, but the text was not linked to the picture itself. Nicholson would have provided an eye-catching dust-jacket illustration, but hardly one that confirmed the title, On the Edge of Paradise. The article "Nicholson's Portrait of A.C. Benson," by Ronald Hyam and J.M. Munns in Magdalene College Magazine, 2018-19, 63-66, is especially useful as the sole extended discussion of Benson's attitude to the way in which he was pictorially memorialised.

The Nicholson portrait is reproduced from the website of the Fitzwilliam Museum under Creative Commons licence, which includes a stipulation that pictures must not be edited. The photographs come from various volumes in the public domain. They have been cropped for emphasis, but my limited technical skills are a guarantee against any editorial distortion.

Material about Magdalene College Cambridge on this website represents the results of my own interest in the history of Cambridge University, and does not imply any endorsement by the College. I appreciate the friendly interest in the website shown by many past and present members of the College. Further material on A.C. Benson and Magdalene College may be found on "History of Magdalene College Cambridge on www.gedmartin.net":

https://www.gedmartin.net/martinalia-mainmenu-3/372-magdalene-history-on-ged-martin-s-website