Magdalene College Cambridge Notes: names and spellings

Magdalene College, Cambridge has existed in two incarnations, under several names and various spellings.

From 1428 until 1539, it was a "cell" (dependency, offshoot, branch plant) of Crowland (in the fifteenth century, Croyland) Abbey in Lincolnshire.[1] In recent times, historians have used the term "Monks' Hostel" for the first half century of its existence, while recognising that it had become known as Buckingham College by 1483. After a brief period in limbo, it was reconstituted in 1542 as the College of St Mary Magdalene in the University of Cambridge. Sixteenth-century English spelling was notoriously random, but it seems safe to conclude that, by about 1600, it was conventionally known as "Magdalen", the version used, then and now, by its Oxford counterpart, founded as Magdalen Hall in 1448 and re-chartered as a college in 1457.[2] In the early nineteenth century, the Cambridge institution added a final –e to its name: Magdalene. Only one College historian, F.R. Salter, has addressed the change in spelling, which he dated to "probably some time between 1816 and 1820". He could not satisfactorily explain it.[3]

It should be stressed that the institution did not acquire a legal personality until its refoundation in 1542. It was only when it became competent to own property (although, sadly, not very much of it) that we have some idea of how its inmates wished to describe their society.[4] By contrast, the hostel for monks that became known as Buckingham College appears only in documents written by others, for purposes of their own. Nor does it help that most of the early sources were written in Latin, an elegant language whose telescoped phrases are usually open to various translations.

Abbot Litlyngton and the Benedictine hostel In a Note mainly focused on names, there might seem to be little call for a detailed history of what Peter Cunich has called – and efficiently described – as "Proto-Magdalene", the eleven decades from 1428 to 1539.[5] Nonetheless, an overview may highlight some new perspectives. Concern had been voiced in the Benedictine Order for some time about the risks of sending young monks to study among the temptations of Cambridge. Individual abbeys already owned some small hostels, but these could not house all the monastic undergraduates, while sharing accommodation with laity created too many temptations. In 1428, the Abbot of Crowland, John Litlyington (or Litlington), persuaded the king's Council that the Benedictines needed their own residence in the university town, and Henry VI authorised its establishment through a device called letters patent.[6] To quote Cunich, it is "not known" why it was Crowland that acted on behalf of the Order, but the choice made some sense. Although Litlyngton was young, he was already experienced and obviously efficient – and would go on to lead the monastery for a remarkable four decades.[7] The fourteenth-century Crowland Chronicle recounted that scholars from the abbey had begun the teaching of sacred theology, logic and rhetoric at Cambridge in 1109, a claim that formed one of the University's confusing origin myths.[8] It would have been natural for Crowland to covet the honour of renewing that association. In addition, the abbey owned the manors of Cottenham, Dry Drayton and Oakington, handily located on the northern flank of Cambridge. (It had been from Cottenham that the monkish professors had allegedly launched the putative twelfth-century University.) In earlier times, these properties had been managed by a resident reeve, an official on-the-spot who might have been useful in establishing the hostel, and it is possible to think of the three manors as sources of supplies, foodstuffs, firewood and timber for repairs. However, by the early fifteenth century, declining crop yields and difficulty in retaining tenants had greatly reduced the value of the estates. Cash rents replaced services, and demesnes were leased to contractors, Dry Drayton in 1415, Oakington in 1429, although the abbey still took its Cambridgeshire estates seriously during the 1420s, attempting to develop large-scale sheep farming.[9]

Abbot Litlyngton was not directly entrusted with the acquisition of premises for their new Cambridge hostel. Rather, he and his fellow monks were to be recipients of property in the parish of St Giles to be conveyed to them by two bishops, Thomas Langley of Durham and William Alnwick of Norwich. A third man, John Hore of Childerley, was also named, although his role was not explained. The Crown charged a fee for exemption from mortmain, the laws that sought to prevent estates from falling into the dead hand (mortmain) of Church control, and the grant firmly specified that all the Benedictine monks studying at Cambridge were required to lodge in the hostel.[10] Some of the participants solemnly mentioned in the formal document may be discounted as serious contributors to the founding of proto-Magdalene. Henry VI, for instance, was a six-year-old boy, and certainly knew nothing about it.[11] (When he did become old enough to lavish his own generosity upon Cambridge, his energies were largely focused on the establishment of King's.) At first sight, the involvement of the two bishops is also a mystery. Neither was a Benedictine, but both were key administrators in the regency that represented the young monarch, Langley as the long-serving Chancellor (a kind of medieval prime minister) and Alnwick as keeper of the privy seal, a role comparable to a modern-day chief of staff. It is hard to believe that they had either the time or the interest to take an active part in a small property transaction in a provincial town, but – as speculatively suggested below – their signatures (or seals) were probably required to transfer rights acquired by the Crown. This leaves the shadowy John Hore of Childerley. The hostel precinct took in two sites: Cunich concluded that the two bishops donated the land along the street front, which stretched back to the site of the later Pepys Building, while he regarded Hore as the donor of the pondyards, the open space that today forms the College gardens.[12]

Discovering John Hore Fortunately, John Hore emerges from obscurity thanks to a biographical essay devoted to him by the History of Parliament project in 1993, which portrays him as a substantial local figure.[13] Welcome as this information must be, a note of caution is called for. The injection of biographical detail into a familiar story may stimulate fresh perspectives, but it also has the potential to distort the overall picture: the fact that we now know more about John Hore cannot obviate the possibility that he was still only a minor player in the establishment of the Benedictine hostel. Nonetheless, he seems to have been an impressive and an intriguing character. Presumably he came from a genteel background, since by 1393 he was a retainer at the court of Richard II. His fortune, however, was acquired through three successive marriages, each of which brought him valuable estates. Through his first wife, Hore became the owner of Great Childerley, nine miles west of Cambridge – with access to the University town along the street that led down to the Great Bridge – and, by about 1400, he had acquired Little Childerley as well.[14] Around 1412, he added estates in nearby Huntingdonshire through a second marriage, this time to a wealthy widow – he was executor to her husband's Will at the time –which he energetically extended. Hore's business methods may have been less endearing than his courtship techniques, since in 1417 he survived a violent physical attack, in which another man was killed. However, he was by now sufficiently prominent to be elected to parliament, successively for Cambridgeshire in 1415 and 1425, and for Huntingdonshire in 1416. To be a county MP – a knight of the shire – was a considerable distinction, yet neither Henry IV – who had ousted and probably murdered his former employer king Richard – nor Henry V ever bestowed local office upon him. No doubt John Hore would have sworn his allegiance to the Lancastrian monarchs, a requirement to serve in parliament, but it is likely that he was regarded with suspicion as somebody emotionally committed to the deposed and martyred king. It was not until 1424, during the minority of Henry VI when an insecure regime needed broad support, that he was given an appointment. It may be significant in the proto-Magdalene story that the job was as an escheator, an official who seized and administered the property of those who died intestate, thereby forfeiting their estates to the king. In 1426, Hore served as sheriff of Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire and, soon after, a third marriage, to yet another wealthy widow, extended his own portfolio into Norfolk. Almost certainly, he was by now in his fifties, the age when medieval people began to ponder their likely fate in the afterlife. He seems to have been attracted to the Benedictine Order – which had also had a loyal follower in Richard II. He arranged to leave property to their house at Ramsey, although he reserved a life interest for his son. Ramsey Abbey did not actually acquire the bequest until 1453 – which may explain why the monks of Ramsey felt obligated to build one of the brick staircases that were added to the Cambridge hostel twenty years later.[15] By 1428, he was mature enough and rich enough to make provision for his soul. These elements alone would help to explain his support for the Crowland project.

A converted inn? Thus far, this recently excavated barrage of historical facts enables us to see John Hore as somebody who was in a position to make a substantial contribution to the establishment of the hostel beyond Magdalene Bridge. Perhaps it is time for an excursion into the realms of assessment and speculation, to explore whether they may throw potential light on events. We may start with the location, which would make Magdalene the only ancient college on the west bank of the Cam.[16] Doubt may be thrown upon one persistent assumption, that the monks were "[a]iming to put themselves at a distance from the temptations of the town".[17] For centuries, the image of Magdalene has been shaped by the narrow central-Cambridge obsession which sees anywhere more than a few yards from the Trinity Street-King's Parade axis as here-be-dragons outer darkness. Thus in 1655, Thomas Fuller, a product of Queens' and Sidney Sussex, called the College "an anchoret [anchorite, hermit] in itself", whose students "though furthest from the schools [examination halls]" were able to live "cheaper, privater, and freer from the temptations of the town".[18] In reality, the new facility was located a few yards from Quayside, the muscular heart of a busy inland port, and alongside the thoroughfare that provided the only access to the town from the north and west. By the sixteenth century (when records are more frequent), it is clear that the street leading downhill from the Castle was lined with inns, competing to serve travellers. They had probably existed earlier: the Victoria County History identifies sixteen establishments by name in the town that can be traced before 1500. Although their locations are not always certain, some of the structures in Magdalene Street are (or were) of medieval date, and they may well have been trading earlier.[19] Over the centuries, the College would eliminate four establishments in the Old Lodge / Master's garden area. Later, it took control of two impressive inns across the road, one of which, the Cross Keys, became undergraduate accommodation, leaving only one licensed premises, the Pickerel, still in operation.[20] Hence the mild comment by Cunich: "while the trans-pontine location of the hostel may have removed the monk-scholars from the temptations and diversions of the town centre, they were still in a rather busy part of the town".[21]

It is possible that the location attracted Abbot Litlyngton for two other reasons. First, the pondyards offered direct access to the Cam, and hence to the immense network of fenland water transport, of which Crowland formed part. It is difficult today to grasp the importance of Cambridge's role as an inland port, linked to the wider world through Kings Lynn, but benefiting from a network of rivers and canals ("lodes") that connected towns, villages and abbeys. A reconstruction of a journey undertaken by a group of students from Cambridge to York in 1319 shows that, travelling by boat, they reached Spalding, ten miles beyond Crowland, in two days – and that was in mid-December, when lack of daylight would have reduced potential travel time.[22] Travel by boat would allow convenient supervision of the hostel from the parent Abbey, but it was undoubtedly expensive: in that era, students often remained in Cambridge year-round to save money. However, even if the young monks could not afford to use the river highway to get home in vacation, they could at least be decanted straight on to the site without having to pass through those wicked downtown fleshpots.[23] Here was the second advantage of the location, its size. Students at a university could not be confined to barracks all the time, but the precinct was large enough to reproduce something resembling a cloistered life. The point was not that it lay in some innocent paradise beyond the bridge, but rather that it was close to what was still the edge of the town, where more space was available than on the busy central streets.[24] Above all, it seems likely that the precinct had ready-to-occupy accommodation.

True, Benson empathetically insisted that the site contained only "[s]ome mean tenements and houses", but Ronald Hyam is almost certainly on firmer ground in suggesting that "the site in 1428 contained a couple of pre-existing houses in the street ... and these sufficed for a time".[25] As usual, the available records do not tell us much, but a little detective work and some brave leaps of imagination may flesh out a story, perhaps even the story. The letters patent are not very helpful, since they simply refer to "two messuages with the appurtenances". This remarkably imprecise description is probably explained by the fact that the document simply authorised the establishment of a hostel, which it exempted from mortmain, empowering Langley, Alnwick and Hore to negotiate a more detailed legal transfer, which would have described the property in appropriate detail. This documentation would have been kept among the muniments of Crowland Abbey as proof of title. Deeds of nearby holdings have survived, but – regrettably – nothing relating to this transaction. As Cunich explains, "the term 'messuage' was usually applied to any dwelling-house with its outbuildings and land, or land which could hold such". Hence his deduction that the two bishops "were persuaded to purchase the land occupied by First and Second Courts", while Hore supplied the site of the College gardens.[26] However, an alternative might be posited, since the pondyards, usually described as a close (i.e. devoid of buildings), may not have qualified as a messuage. There is generally accepted evidence for the existence of two fifteenth-century structures along the street front of First Court.[27] This is simply deduced from the building history of the College. The northern section of the west range, from A staircase to the start of the porters' lodge (the former B staircase, eliminated when the lodge was enlarged in the 1960s) is authoritatively dated to around 1480. The southern section, from the lodge to C staircase, was filled in around 1585, thanks largely to a benefaction from an Elizabethan judge, Sir Christopher Wray. It may be possible to go further, and suggest that there was some entrance space between the two buildings, giving access to a yard behind – maybe the "appurtenances" mentioned in the letters patent. As Ronald Hyam pointed out, there is not only "a very sharp break in the character of the brickwork" but the internal partition at the back of the porters' lodge is "unusually thick". This suggests that the fifteenth-century range terminated in an external wall. This gap probably provided the original gateway to the hostel. Its ghostly trace survives in the path across First Court to the screens passage, angled because the replacement gateway of 1585 was moved slightly to the south.[28]

It may be possible to go even further in imagining the site of the hostel in 1428. First, even allowing for a gap between them, it seems likely that the two structures were relatively large buildings, with street frontage considerably longer than the surviving Cross Keys block across the street. We may also note that they had apparently been combined to form a single property, which explains why both messuages were available for acquisition. Could the premises have been in use as an inn? It would have been one of the larger establishments in Cambridge, probably with outbuildings that covered much of First and Second Court. Such hostelries were not unusual. In the early sixteenth century (and perhaps earlier), the Dolphin stretched from All Saints churchyard to Bridge Street. In the seventeenth century, the famous carrier (and no-option supplier of horses) Thomas Hobson ran the George in Trumpington Street, later absorbed by St Catharine's, which comprised not only barns and stables but an orchard. Other large inns have left their mark on the city's street plan: the Black Bear as Market Passage, the Red Lion in the Lion Yard complex.[29] It made sense for hospitality enterprises to be located on the edge of the urban area: as Purnell wordily put it, "the multiplication of inns here being doubtless due to the market-folk putting up at the entrance to the town".[30] By the late-fourteenth century, there were around two dozen such hostelries in Southwark High Street, the main approach to London from Kent. Of these, the Tabard offered medieval five-star accommodation to Chaucer's Canterbury Pilgrims: "The chambres and the stables weren wyde / And wel we weren esed atte beste". Half a century later, we might expect to find a similar facility in Magdalene Street. We might further guess that it had come into the hands of the Crown as a result of intestacy, probably while Hore held the office of escheator for the county. It is evident that representations had been made on behalf of Crowland Abbey to the Council sometime before the letters patent were issued in July 1428. Since its abbot was usually summoned to parliament, it is likely that John Litlyngton journeyed to London for the session of 1427. We may imagine him, recently elected and full of enthusiasm, inspecting the Crowland estates on his way south. Dry Drayton is the next parish to Childerley. Courtesy would have led Hore to offer hospitality. Doubtless the abbot described how the Benedictines needed large enclosed premises in which to establish a well-disciplined student hostel. John Hore knew the very place, a property that would not only sleep several dozen studious young monks, but was also supplied with kitchens to feed them, and communal space that could be used for teaching and worship. If the business was actually functioning, it would even come equipped with a staff of scullions and skivvies to smooth the transition. Moreover, having just made a third lucrative marriage, Hore was in a position to safeguard his middle-aged soul by paying for the property himself. All that was required was to persuade the Council to sell. With a war in France devouring cash – in 1427, even bills from the Agincourt campaign twelve years earlier remained unpaid – and the regime forced to borrow at interest rates of up to 33 percent, this would not have been a huge challenge.[31]

However, it must be admitted that this scenario faces a problem, in the formidable shape of the pioneer historian of medieval law, F.W. Maitland. Property was forfeited to the king through treason, felony and intestacy. The first is unlikely: there had been plots against the Lancastrian monarchs between 1400 and 1415, but no recent conspiracy that might have triggered such a windfall. The goods and chattels of criminals became the property of the town, not the Crown – no doubt an incentive to encourage Cambridge to pursue its criminals. Most inconvenient of all was Maitland's assertion that escheat through intestacy was "rare, very rare" in Cambridge, apparently because the burgesses could bequeath their property without any feudal intervention.[32] However, this might not have prevented the sudden elimination of an innkeeper and his whole family through a lightning outbreak of disease that permitted no time for the formal disposition of their assets. Cambridge seems to have been free from major outbreaks of bubonic plague for almost a century after 1389, but there were plenty of other afflictions that were both quick and lethal: in 1442, Henry VI decided not to attend the laying of the foundation stone for King's College chapel because of " the aier and the Pestilence that hath long regned in our said Universite".[33] Equally, the inn might have been owned by a Cambridgeshire resident as an investment, and been seized by a county official, such as John Hore, as part of his estate if the proprietor had died without leaving a Will. It might even be objected that there is no need for the escheat hypothesis at all, since Cambridge shared in the general urban crisis that swept late fourteenth-century England, and the town would have had ample vacant property, probably cheap to purchase.[34] However, a transaction on the open market would hardly have required the participation of two bishops holding key administrative offices. It is surely the case that Langley and Alnwick were not, as Cunich concludes, "persuaded to purchase the land" but rather that they – or clerks responsible to them – were commissioned to negotiate with John Hore for the sale and transfer of a piece of fortuitously acquired Crown property to Crowland. Like most coalitions, the Council governing England on behalf of Henry VI had its internal tensions. In 1427, faced with the pretensions of the boy king's uncle, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, who believed he was entitled to act as regent, its members decreed that no one person "may owe or ascribe to himself the said rule or governaille" – in other words, that none of them should take sole responsibility (or claim personal credit) for any of their actions.[35] Hence the cumbersome procedure of naming two busy ecclesiastics nominally to oversee the sale of a couple of messuages in a Cambridge street.

I venture to explore the imagined Magdalene Street inn a little further. It has already been suggested that the gap between the two street-front messuages opened into a yard. Lyne's map of 1574 shows two projecting wings behind the Pickerel, on the opposite side of the street. By the time of Loggan's map of 1688, these extended as far as Bin Brook, and similar outbuildings ("appurtenances") were attached to other local inns. An establishment serving travellers at the edge of the town would certainly have needed extensive stables. There were houses between the site and the Great Bridge, some of them probably used for industrial purposes.[36] It would have made sense to have the stables up against that urban enclave, running along the south side of the inn yard. Perhaps they were later converted – one hopes, after extensive fumigation – into cubicles for the student monks. Half a century later, these were superseded by D, E and F staircases. A respectable inn would also have required high status accommodation, a suite of rooms suitable for passing dignitaries, such as bishops, knights and nobility. The logical position for these would have been in an inner north range, away from the busy street and as far from the stench of the river as possible. It is surely no coincidence that, by 1480, we find there the handsome rooms of the prior studentium, the director of studies who supervised the young monks – spacious apartments that became and remained the Master's Lodge until 1837.[37] As a precaution against fire, kitchens and bakehouses were generally located in free-standing structures away from other buildings – possibly close to the east side of First Court where permanent kitchens and buttery were erected, probably early in the sixteenth century, and certainly before 1519. Thus far, cynics may note that the alleged appurtenances would all have vanished under fifteenth- and sixteenth-century brickwork, where the archaeologist's trowel cannot now pursue them. However, there is no reason to assume that an inn yard would have been as neatly arranged as a subsequent college courtyard. Centuries of levelling, landscaping and the dumping of rubbish will have encumbered the Magdalene precinct with a cacophony of archaeological noise, but it may be that a geophysics survey could find traces of earlier buildings. Searching for them, whether to confirm or explode this hypothesis, would form a suitable contribution to the observance of the six-hundredth anniversary.[38]

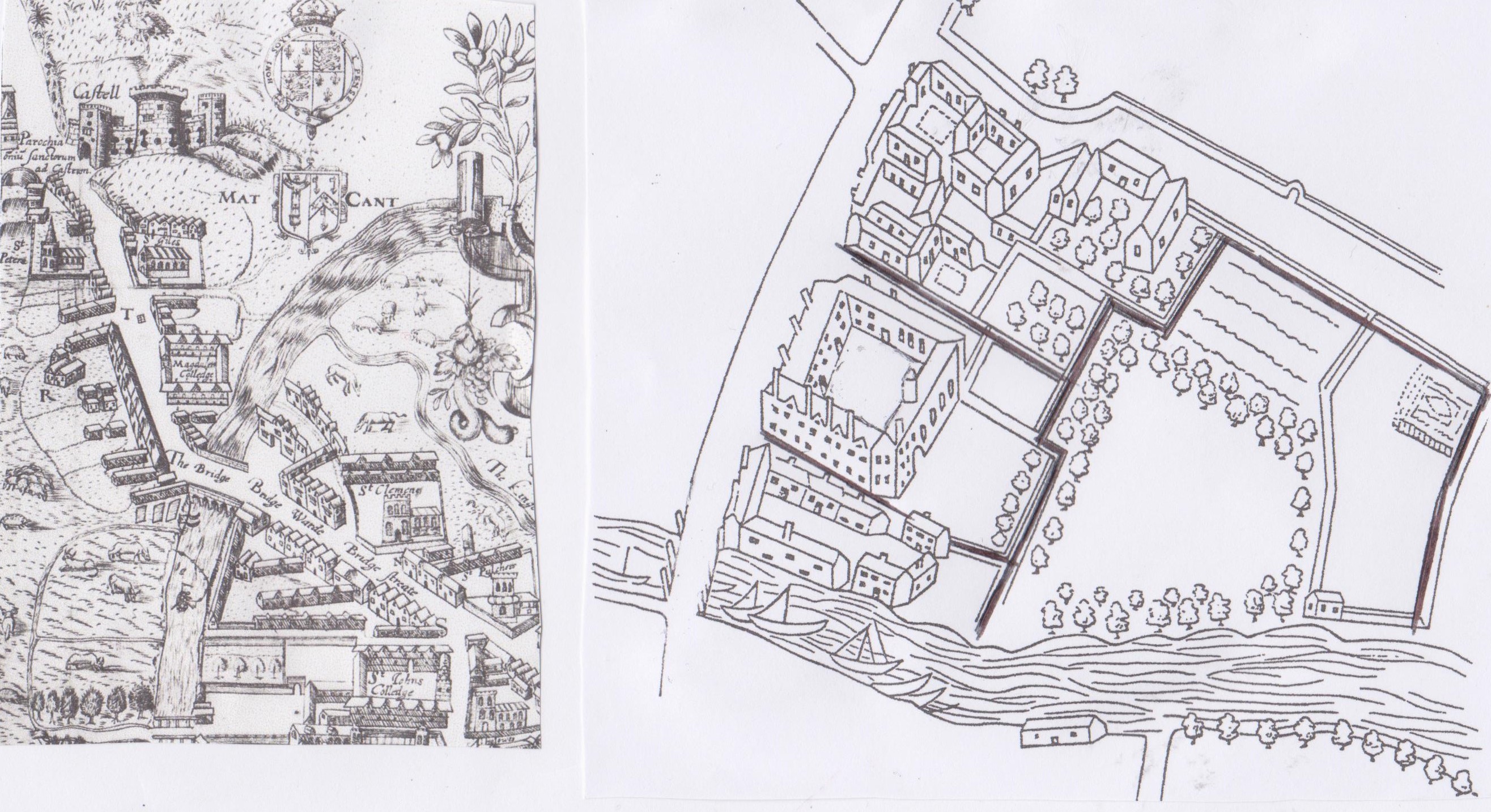

(Left) Part of the map of Cambridge by Richard Lynes, 1574. Although the thumbnail sketch of Magdalene's First Court is probably stylised, it does seem to indicate a gap half way along the street-front, probably the site of a gatehouse (on the site of the present Porters' Lodge) and a small garden. The two long ranges on the west side of the street were probably part of the Pickerel inn yard. St Giles' and St Peter's churches are marked at the foot of Castle Hill; St Clement's and the Round Church are across the bridge. R on the map represented the School of Pythagoras, the medieval town house now forming part of St John's. More mysteriously, T (at the top of Magdalene Street) marked a cast-iron fence (perhaps a cattle grid?) which Lynes believed indicated a former course of the Cam. (Right) Hammond's map of 1592 shows the College after the completion of First Court c. 1585, and the in-filling of the pondyards c. 1586 (although wavy lines alongside Chesterton Lane may suggest water?). Black lines highlight the boundaries of two messuages of 1428 (First and most of Second Court) and the pondyards (now the College garden). The River Court / Bright's Building area was acquired c. 1793.

1428-72: a hostel without a name? None of this reconstruction brings us any closer to discovering the name of the new foundation. Putting flesh on the bones of John Hore and hailing him as the precinct's first benefactor seems an overdue act of justice, but perhaps it was for the best that his name was not associated with the new hall of residence, unlike –say – that of Edmund Gonville, who had launched a similar project back in 1348. Godshouse, Michaelhouse and Peterhouse are enough to indicate the potential embarrassment that might have been associated with any such appreciative commemoration.[39] On the analogy of the three Benedictine establishments at Oxford, named after their houses at Canterbury, Durham and Gloucester, we might have expected the Cambridge hostel to be formally associated with Crowland, but this evidently did not happen.[40] The abbey was a middle-sized community: 41 monks, just three of them novices in 1324, numbers which fell in the later fourteenth century, recovering to 36 in 1440 and 41 five years later, before slipping back to 32 in 1534 and just 28 at the Dissolution in 1539. In 1440, Crowland had only two students studying at Cambridge.[41] By contrast, even after a century of falling numbers, Christ Church Canterbury still housed 70 monks in 1500, Gloucester Abbey 50, while Durham usually had six novices being prepared for Oxford.[42] Crowland was simply not big enough to impose its institutional personality, and hence its name, on the Cambridge project. Twice, the office of prior studentium was filled by a monk from St Mary's Abbey at York, although it was John Wisbech of Crowland who took the lead in the building programme of the 1470s. Yet the project seems to have remained the preserve of the Fenland abbeys, plus the nearby house at Saffron Walden. The apparent lack of involvement on the part of the immensely wealthy monastic community of Bury St Edmunds, not thirty miles away, is striking. The abbot closed its own Cambridge hostel in 1433, no doubt in response to the insistence of the letters patent that all Benedictine students in the University should reside in the new establishment. However, Bury's links were primarily with Oxford, where it traditionally supported four students at Gloucester Hall.[43] Other substantial – and wealthy – Benedictine foundations, such as Peterborough, St Albans and Westminster, were hardly remote, but have left no trace in the admittedly opaque story of the Cambridge community. Most remarkable of all was the case of the Benedictine monks of Norwich, who refused to abandon their links with Gonville Hall and Trinity Hall. The fact that they went to the trouble to secure a papal bull in 1481 confirming this arrangement suggests that they were resisting pressure to contribute to the programme of renewal that had been launched by Abbot Wisbech, and which was still incomplete.[44] Lack of enthusiasm from some of the richer Benedictine houses probably explains why he sought external sponsorship for the rebuilding of the 1470s.

Perhaps, lacking as it did any legal personality or independent existence, the Magdalene Street hall of residence did not need a formal name. It was referred to in a deed of 1472, apparently of an adjoining property, as the "hostel called Monks' place", but this is presumably a translation of a Latin phrase that might have carried other connotations.[45] Similarly, the section of the Crowland Chronicle written about 1486, after it had acquired a sponsor's name, called it "Collegio monachorum Buckinghamiae": this might be "Buckingham College of the monks", "the monks' college of Buckingham" or, more loosely, "the monastic College of Buckingham". One obvious candidate for an informal local nickname, the Benedictine hostel, was ruled out because Corpus Christi was known as Bene't College: its inmates prayed in the parish church next door. (The Crowland offshoot was located in the parish of St Giles, which belonged to Barnwell Priory – an Augustinian foundation – hence it is not clear whether there was a close relationship between the hostel and the nearby church.) How, then, have we come so confidently to call it the Monks' Hostel? Writing in 1574, Dr John Caius did not name the establishment at all. Thomas Fuller, in 1655, boldly called it "Monks' College".[46] Speculation seems to have lapsed for two centuries: J.W. Clark in 1886 noted a "legend" that the name was "Monks' Corner", but he broadly hinted that this was a romantic name for the recesses of the College garden.[47] E.K. Purnell, Magdalene's first stand-alone historian, called his opening chapter "Monks', Later Buckingham College", but avoided committing himself to any specific designation in the text. The first explicit description of the foundation as "Monks' Hostel" seems to be in Benson's short history of 1923, again a chapter title, with his sole textual statement that the place was "called Monks' Hostel or Monks' College".[48] It was the quincentenary appeal for cash needed to construct a new court that explicitly invoked five hundred years of "Magdalene College Cambridge formerly Monks' Hostel 1428-1542-1928". This was a wholly pardonable decision, since chequebooks were hardly likely to fly open in celebration of the five-hundredth birthday of an institution that nobody could even name.

However, there may have been another element in this process. In the years after the First World War, pressure of numbers forced the creation of a new Magdalene. The forty undergraduates of late-Victorian days had swollen to a community of 180 students, and the days when they could all spend three years in College had gone for good. With lodgings in private houses increasingly difficult to procure, Magdalene – in common with other colleges – was forced to establish hostels. By 1928, there were three of them. The Appeal brochure of that year indicated an embarrassed sense that they represented a second-class Cambridge experience, but there was little doubt that hostels would be a permanent feature of College life. Perhaps the dons of Magdalene reacted subconsciously, but it was a characteristic Cambridge device to disguise change by portraying it as a revival of past practice. Boarding in Kingsley House or Mallory Court (which was originally not included within the academic precinct) might be less atmospheric than "keeping" in rooms overlooking First Court or high in the Pepys Building, but somehow the exiled undergraduate was in touch with centuries of lost tradition.[49] By a process of historical sleight of hand, Magdalene historians – myself included – came to accept that the institution had originally been formally titled the Monks' Hostel (usually with the definite article). In reality, we have almost no idea what the place was called during its first half-century as a place of study.

Buckingham College From 1483, we are on firmer ground. That year, the town's local tax record mentions payment by the Abbot of Crowland for a hostel called "Bokyngham College". The reference to "Collegio monachorum Buckinghamiae" in the Crowland Chronicle is slightly later, but refers to the building programme begun by Abbot John Wisbech, who was in office from 1470 to 1476, and to which it was assumed Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham had contributed. Thus we may conclude, with Cunich, that the new name dates from "some point" in that decade.[50] It should be noted here that, even if there was some sort of re-launch, we still know very little about the institution. "Evidence for the story of Buckingham College is very scanty," R.W. McDowall remarked in 1952, and most commentators have echoed his complaint. The principal traces are easily summarised. In 1502, the town authorities evidently determined to crack down on nuisances. One problem was the obstruction of streets by stacks of timber. The Prior of Buckingham College was presented (i.e. threatened with prosecution) "for having blocks of wood lying before that College". Whether this represented firewood, or implied some forgotten construction project, it is impossible to say. At the same time, the town also censured the "master or keeper" of Buckingham College for erecting privies that discharged into the Cam, although it seems unlikely that these were a new feature. The following year, local records mention the "Mancipil of Bokyngham College": a manciple was a catering manager, confirmation of the obvious point that the Crowland hostel fed its inmates. Within a few years, it becomes clear that the institution had become a recognised part of the University. In 1514, it appeared in the proctorial cycle, taking its turn to nominate members of the academic police force. From around 1500, some students and teachers can be identified by name. In 1519 (so tradition dates it), a fine collegiate Hall was built, by another Duke of Buckingham, Edward Stafford. In 1535, Buckingham College was required to contribute lectures in Greek and Latin to a new humanistic curriculum. Yet none of these allusions emanated from within Buckingham College itself, simply because the attribution was a misnomer, a term politely applied to an institution that was not chartered, self-governing or independent and hence had no capacity to issue statements on its own behalf. When Crowland Abbey surrendered to Henry VIII four years later, we cannot even say that Buckingham College also formally closed its gates, since – technically, at least – it had never existed in the first place.[51]

The received story of the rebuilding programme of the 1470s may be briefly summarised. Abbot John Wisbech embarked on a programme of building chambers suitable for accommodation and study. He enlisted the support of the second Duke of Buckingham, but for some reason the project had to be completed by the abbeys of Ely, Ramsay and Walden, each of which built a staircase, presumably retaining rights to demand rooms in their own investment. Abbot Wisbech's motives are unknown, but can be guessed. Perhaps Crowland had grown somnolent under the very long rule of John Litlyngton, and he felt the need for some striking project. If the hostel had indeed taken over the premises of a working inn, after half a century it probably required refurbishment. Fifteenth-century monks hankered after a comfortable lifestyle, and an obscure phrase in the account by Dr Caius suggests that more of them wished to come to Cambridge.[52] A wish to emulate, and compete with, the comfortable Benedictine facilities at Oxford may also have been an incentive. However, as Cunich carefully explained, it is harder to account for the involvement of Buckingham. He had no particular connection with the Abbey, and the Crowland Chronicle is hardly polite about him. However, this section was written after the Duke's execution in 1483, when his reputation had been tarnished, first by abandoning Edward IV's young sons, the famous Princes in the Tower, and then by rebelling against the usurper, Richard III, and – worse still – carrying out his revolt ineptly. The problem is that Duke Henry did not control his inheritance until he reached his eighteenth birthday in 1473. Although enormous estates made him one of the richest landowners in England, extreme wealth was usually inextricably entangled with massive debt, a problem that limited the options of his son, Edward, the third Duke, when he resumed the patronage of Buckingham College around 1519. Cunich plausibly argues that the financial support for the rebuilding programme came from the young nobleman's grandmother, Anne Neville, widow of the first Duke, who was held in unusual honour by the monks. This is entirely possible: Clare, Pembroke and – later – Sidney Sussex were all founded by noblewomen, but in each case the college took its name from the (male) family title.[53] We have only the authority of Dr John Caius, writing a century later, for the belief that Henry Duke of Buckingham began building in brick, and that the institution derived its name accordingly. Since Dr Caius could not provide anything like a precise date, it seems likely that he was not working from any documentary source, but merely citing academic hearsay.

A consensus has emerged that divides the 1470s construction into two segments. To understand the new name, we need to explore the connection between them. The Buckingham-funded Crowland contribution was the north range of First Court, comprising the Chapel and the prior's apartments, now the Parlour and the Old Library (or, perhaps more likely, the rooms above them), plus what is now A staircase, replacing the northernmost of the two messuages of 1428.[54] Separately, the staircases built by the abbeys of Ely, Ramsey and (Saffron) Walden are generally assumed to be D, E and F, on the south side of First Court. Given the distinct layout of each of these three staircases, this makes sense. Unfortunately, the interpretation was for long complicated by an observation made in 1777 by the antiquary William Cole, who spotted the arms of Ely Abbey over the archway in the north-west corner of First Court, leading to the assumption that Ely had constructed A staircase. However, since the heraldry was upside down, it is permissible to assume that this was a clumsy repair job, perhaps perpetrated much later when the interior of First Court was barbarically covered with stucco in 1760.[55] Thus we have two separate but related building projects – but how do they relate, in time and in purpose, and what light can they throw upon the name?

Dr Caius simply described how the Duke began construction in brick, while others built another section ("dum aliam partem alii aedificarunt"). But Purnell quoted a sentence from the Cotton MSS in the British Museum (now British Library), which implied a sequence. " Aedificare incepit Henricus, dux Buckinghamiae, sed intermissa aedificia abbates Elienses, Ramsienses et Waldenses prope absolverunt." (Henry, Duke of Buckingham, began to build, but when the building was interrupted, the abbots [or abbeys] of Ely, Ramsey and Walden quickly stepped in.) As always, much depends on the nuances of translation. The verb "absolvere" can mean to liberate or to absolve, as we would expect, but it can also mean to continue, as is probably intended here. It is intriguing when put alongside "intermissa aedificia", the suggestion of an interruption in the Duke's activities perhaps carrying with it the sense of our word intermission, and with it the assumption that he might in due course resume his support. Thus, as Dr Caius seemed to imply, in taking on part of the project themselves, the three abbeys were not letting Edward Stafford permanently off the hook. Unfortunately, Purnell did not identify the extract from the Cotton MSS, which were assembled in the early seventeenth century.[56] Hence it is impossible here to determine whether it was an elaboration imaginatively derived from Dr Caius, or the product of some independent tradition. If the Cotton MSS source is reliable, it would help to explain not merely how the Duke's name came to be associated with the hostel, but why it was retained even after he had apparently failed to deliver.

However difficult it may be to pin down, the timing of construction around First Court is of some importance in relation to the appearance of Buckingham College in the local tax register of 1483. (This, it should also be remembered, is simply the first such list to survive, and therefore does not disprove the adoption of the name some years earlier, as implied by its retrospective use in the Crowland Chronicle.) The Chronicle's statement that buildings were erected by Abbot John Wisbech may not necessarily mean that they were completed by the time of his death in 1476. Construction in brick, complete with timber fittings, was probably not an overnight operation, especially as benefactors tended to provide cash in instalments, which might be delayed.[57] It does not help that the ducal project and the abbey staircases are linked by two Latin conjunctions, with slightly different meanings: "dum" (while) in Caius, "prope" (close) quoted from the Cotton MSS. The first could imply that the work on the north and south ranges was carried on simultaneously, in which case the involvement of three abbeys was only loosely connected with the Buckingham largesse. The second suggests that there was a short interval between the stages, but this in itself cannot prove that Ely, Ramsey and Walden became involved because the Duke had defaulted. Religious houses were not construction companies, and perhaps they needed time to gear themselves up to design and erect their staircases. Here the fact that the Benedictine monks of Norwich thought it worth securing the support of Sixtus IV in distancing themselves from the Order's Cambridge hostel in 1481 may suggest that they were under pressure to make some contribution: papal bulls did not come cheap, nor were they rapidly procured. Nor should we forget that we have one architectural conundrum that leaves its mark in the brickwork of First Court to this day: the west range was left incomplete, and remained so for one hundred years, leaving a gap, presumably comprising one of the original messuages, between the two brick structures, which was surely a reproach to institutional self-respect. Could it be that the "intermissa aedificia" resulted from the Duke of Buckingham's execution in 1483 – that same year that we know the townsfolk associated his name with the Crowland hostel?

It seems worth pointing out here that discussions of the origins of names tend to concentrate on the reasons for their emergence, coupled with explanation of their significance. In addition, there is a deeper issue of process that is generally ignored, but which is of importance in understanding the Buckingham label. There are two ways in which places and institutions acquire their names – the first through community consensus, the second through deliberate promulgation on the part of some sort of authority, such as a founder, government agency or property developer. Since the sixteenth century, certainly in the western world, the second process has dominated, perhaps as a side-effect of the spread of printing. Thus, of 64 jurisdictions that comprise the United States and Canada, only one – Newfoundland – can be said to have acquired a European name through popular invention.[58] The remainder, starting with the coinage of Virginia in 1584, traditionally attributed to Walter Ralegh, have been specifically designated, as we might say, from above.[59] By contrast, medieval place names in Britain and Ireland almost all evolved through word of mouth and were shaped by popular etymology. There were, however, a few exceptions. The Essex village recorded in Domesday Book as Fulepet became Beaumont, presumably because some Norman interloper preferred his address to be Fair Hill rather than Foul Pit. On founding a town in twelfth-century Hertfordshire, the Knights Templars decided to call it after the Mesopotamian city of Baghdad. (There are some processes of medieval thinking that must permanently elude us.) They used the French version of that name, Baudac, which, with some intervention from local usage, settled down as Baldock. Where colleges were concerned, the picture was more complicated. There were instances where a nickname came to define the institution: Bene't College for Corpus Christi and, perhaps most notably, Brasenose in Oxford, believed to have been named in mocking honour of a splendid door-knocker, and this despite the fact that accessory went missing for five hundred years. In fifteenth-century Cambridge, there was no consistency. St Catharine's, founded in 1473, was known by its dedication, interpreted as Catharine Hall until 1860. By contrast, the Royal College of St Nicholas became King's (1441), while the College of St Margaret and St Bernard (1448) was known as Queens'.[60] These by-names may have been popular inventions, but they could have been adopted and fostered by the institutions themselves, for there would have been something of a swank factor in claiming association with royalty. There is also the intriguing case of "The College of the most Blessed Virgin Mary, Saint John the Evangelist, and the Glorious Virgin Saint Radegund", founded in 1496. Tradition claims that its founder, Bishop John Alcock, wished it to be generally known as Jesus College, although it is puzzling that he did not so formally name it.[61]

Thus the question that rises with regard to the emergence of the name Buckingham College is whether it arose spontaneously among the local population or was consciously chosen by Crowland Abbey and the Benedictine Order at large? If the latter, are we perhaps looking at a very early example of the sale of naming rights that would one day lead to the O2 Arena and the Emirates Stadium? The conundrum will probably remain an unsolved mystery, for that very basic reason that no letters patent, charter or statutes were ever issued by or for Buckingham College. However, it may help to illuminate a related issue: why did the apparently informal name survive the execution of Duke Henry in 1483, continuing into an era when his reputation was deservedly held in widespread contempt? Once again, Cunich is our guide among the dynastic politics of the period. The monks of Crowland had no interest in honouring the fallen nobleman, but they did require the political patronage of Henry VII's mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, a local landowner and hence vital ally in controlling the unruly Lincolnshire farmers. She was also the great-aunt of Duke Henry's two young sons, who were entrusted by the first Tudor king to her care.[62] Perhaps equally important was the new monarch's gesture of reconciliation, in restoring the elder boy, seven year-old Edward, to the dukedom of Buckingham. The monks might hope that, in due course, the third Duke would honour his father's memory by re-asserting his sponsorship rights over their Cambridge hostel. Coupled with this were elements of simple inertia. Once a name got into popular currency, it was hard to shift: Cambridge borough records continued to refer to Buckingham College until 1550, eight years after its refoundation as Magdalene. In any case, the monks were to a considerable extent stuck with the Buckingham association. As part of the deal to secure the erection of the new buildings, the Benedictines would have undertaken to pray for Duke Henry's soul, an obligation that could hardly be dumped, all the more so because the disreputable culmination of his career meant that he needed all the posthumous spiritual support that organised holiness could supply.

The third Duke of Buckingham eventually provided a further instalment of external support, and is regarded as having constructed the Hall in 1519. It was not his first contribution to Cambridge. The problem, from the Crowland hostel point of view, was that his guardian, Lady Margaret Beaufort, was also an academic benefactor, indeed the (re)founder of Christ's in 1505 and a supporter of St John's, which was formally inaugurated by her executors in 1511, two years after her death. Presumably under his great-aunt's influence and guidance, in early adult life the young Duke made gifts to Christ's, Michaelhouse and Queens'. The low priority that Edward Stafford evidently assigned to the institution that shared his title would seem to indicate that any agreement between the family and the monks had been merely informal, and that it may have taken some effort to persuade him that the Benedictines had any claim upon his largesse. Worse still, by the 1510s that largesse was less than munificent: not withstanding his enormous wealth, Buckingham was deeply in debt. Cunich suggests that they enlisted his support during a visit to Cambridge in 1513-14.[63] This could fit well with the evidence that points to the construction of the kitchens some time before the erection of the Hall. Once again, it is important to remember that brick buildings did not go up overnight: the tracery and glazing of the giant windows alone would have required intricate and time-consuming work.[64]

It had taken forty years for the nominal Buckingham connection to deliver a second dividend, but eventually it had come in the form of an undoubtedly handsome Hall. The monks might reasonably have hoped that their patron would solve his financial problems, and return to complete their courtyard.[65] In the event, he was charged with treason and executed in 1421.[66] His father had been beheaded by Richard III after a failed attempt to link up with Henry Tudor, who gratefully restored the dukedom when he became king. There would be no such forgiveness in the next generation. Buckingham's son and heir, Thomas Stafford, remained a mere commoner until 1547, when he recovered the lowest of the family titles, a mere barony. Most of the dynastic wealth was swept away by a retrospective act of attainder in 1523, and was never recovered.[67] By the time Crowland Abbey surrendered itself, and its Cambridge cell, to the Crown on 4 December 1539,[68] the Buckingham label had ceased to offer any potential advantages. Yet, while Purnell may have been right in suggesting that the name was "doubtless offensive to the king", there would have been simpler ways to erase its existence. The Dissolution was accompanied by large scale destruction of monasteries, and the cost of demolishing an incomplete courtyard in a Cambridge street could probably have been recouped by recycling the bricks and timber. The challenge raised by the institution between 1539 and 1542 lay not in any need to rewrite the past but rather in its persistent, if almost certainly tenuous, continuation into the present. Buckingham College, which had never formally been born, now stubbornly refused to die.

The "missing years", 1539-42 The interregnum (or interruption) between 1539 and 1542 "has always presented problems for historians".[69] In the absence of any College archives, the evidence is slight, merely inferential although, in recent times, it has been regarded as persuasive. The University petitioned the king to take over abandoned monastic buildings in the town, but did not include the Crowland cell in their wish-list. Somebody continued to pay the local property tax on the pondyards in the name of "Buckyngham College". Presumably, some sort of communal life was being maintained. The obvious question that arises in regard to these "missing years" is financial: how did an institution with no endowment manage to struggle on? The nearest it possessed to an assured income was the rent from the pondyards, barely £1 a year. However, the key here may be that both students and teachers were monks, who were provided with pensions at the Dissolution. The younger men would not have received much cash, but the more experienced senior members – there could hardly have been many of them – perhaps felt able to keep the enterprise afloat in the desperate hope that the nightmare of the Henrician Reformation might go into reverse gear. Final examinations for the BA, in the form of oral "disputations", were taken during the fourth year of study, the various tests culminating in the week before Easter. By the Michaelmas Term of 1539, it would have been clear that the monasteries were doomed, and it is unlikely that any of them sent novices to Cambridge. But, a year earlier, the Class of 1538 had probably matriculated in normal fashion, and by December 1539 had perhaps acquired sufficient corporate loyalty to wish to remain within familiar walls. Deprived of their hopes of a life in the cloister, students probably hoped for preferment as parish clergy, for which a university degree was a useful qualification. Maybe they were allowed to complete their second year at Buckingham College, on the understanding that they would then relocate to other establishments for the remainder of their studies. Then, on 10 June 1540, their arch-enemy Thomas Cromwell was dramatically arrested, and lost his head at the end of July. Henry VIII turned to more conservative counsellors, and Buckingham College was encouraged by the apparent U-turn to reassemble that autumn, intent on seeing its final cohort of students through to graduation in 1542. Easter Sunday that year fell on 2 April; the letters patent refounding the institution as Magdalene College were issued on 3 April.[70] This looks like a smooth transition, not the belated kick-starting of a dormant institution.[71]

Magdalene would become cautiously aware of its Buckingham past during the eighteenth century.[72] By the nineteenth, Magdalene had embraced a wholly spurious origin myth which claimed that the third Duke had bought out the monks and established his own college when he paid for the Hall. Although neither Clark nor Purnell endorsed this tale, the annual Cambridge Academic Calendar continued to give 1519 as the foundation date until the eve of the First World War. In 1968-70, the name Buckingham Court was applied to new student accommodation.[73]

Thomas Audley and John Hughes It has to be said that Thomas Audley has not received a vast amount of posthumous gratitude for his establishment of Magdalene College in 1542. The time-serving lackey of an unstable tyrant, he was hardly the founder any college would have chosen, nor is it easy to understand why an apparatchik, notable both for greed and betrayal, should have made such a gesture. "It is difficult to find a convincing explanation for this isolated and uncharacteristic act of altruism, for the refounding of Magdalene is completely inconsistent with Audley's general behaviour during the last fifteen years of his life."[74] Audley's possible motives are reviewed later, but for the time being it is sufficient to note that, in recent times, emphasis has been transferred to the men around him, especially his domestic chaplain, John Hughes. Indeed, so entrenched has the revised story become that it has even been said that: "If there were any justice in history, Magdalene ought really to be called Hughes Hall."[75]

John Hughes was a Welshman and an Oxford graduate. Of his commitment to the refounded College there can be no doubt, for he promptly endowed Magdalene with estates in North Wales, showing considerably more generosity and speed than his employer.[76] Once Audley established Walden Abbey as his principal residence, from 1538, Hughes would have had opportunities to strike friendships in Cambridge, just fifteen miles away, but there is no evidence that he had any previous connections with the University. Cunich identified an impressive array of Benedictine scholars who are thought to have passed through Buckingham College, some of whom may be assumed to have encouraged Hughes to adopt the orphan hostel. Thanks to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, which appeared a decade after the College History, more light can be thrown on some of these personalities. Of course, the most we can conclude is that several of them were in a position to provide support, although we cannot know that they actually became involved.

One possible candidate for membership of a Magdalene College cheer squad was Thomas Holbeach (alias Rands). He had spent around a decade studying in Cambridge, achieving a doctorate in theology in 1534. The following year, he became the last known appointment to the office of prior studentium at Buckingham College. Cranmer regarded Holbeach as one of only two Benedictines who possessed "all qualities meet for an head and master of an house", and in 1536 he was whisked away to become prior of Worcester. There is no record of the appointment of any successor at Buckingham College. Since it is improbable that the Benedictines would have scrapped their academic programme in the year that the closure of the smaller monasteries was (allegedly) intended to encourage the larger houses to reform, it is likely that he retained the nominal office and informally appointed a deputy. Unfortunately, in turbulent Reformation times, membership of an institution did not necessarily imply loyalty to its survival, and Holbeach was undoubtedly ambitious. Moreover, at the time when the fate of Buckingham College was in doubt, he had his own career to protect: Worcester's cathedral priory was dissolved in 1540, but it was not until January 1542 that he became dean of the reconstituted cathedral. (Two years later, he was made a bishop.)[77] Another Cambridge-educated Benedictine, John Chambers, made a more comfortable transition through the Dissolution. Elected Abbot of Peterborough in 1528, he is said to have spent the next decade studying theology, graduating as a bachelor in theology in 1539: he could hardly have been a resident student. His abbey surrendered to the Crown in 1539, but Chambers was appointed keeper of its temporalities (on a generous salary). Two years later, in October 1541, he was consecrated as the first bishop of the new diocese.[78] It was reasonably certain that Peterborough would survive in some form, because Henry VIII's first wife, Catherine of Aragon, had been buried there as recently as 1536: although repudiated in life, she could hardly be dishonoured in death. Thus Chambers probably felt more secure than Holbeach, he was located much closer to Cambridge and had recently studied in the University, presumably having an affiliation with Buckingham College. Whether he exerted himself in its interests cannot be known.

Holbeach and Chambers were Benedictines on the make, in positions where they might have exercised influence on behalf of Buckingham College, but neither with an overpowering motive nor an obvious link to Audley. A third member of the Order slots more neatly into the personalities and the politics behind the refounding of Magdalene. John Capon was a monk at St John's Abbey, Colchester. He too had an alias, Salcot, which suggests that he was born in the Essex marshland village of that name.[79] He studied at Cambridge during the early years of the reign of Henry VIII, graduating with a doctorate in theology in 1515. On his return to Colchester, he became prior (in effect, number two) at the Abbey. At the same time, the rising lawyer Thomas Audley was the borough's town clerk, and it is likely that the two men knew one another. Promotion came to Capon quickly, probably through cultivating political support. In 1517, he became abbot of St Benet Hulme (sometimes "Home"), a Benedictine house in the Norfolk Broads. He might well have kept in touch with Audley, since it would have been logical to stop overnight at Colchester on journeys to London. Capon also maintained close links with Cambridge, where his brother began a thirty-year reign as Master of Jesus College in 1516. One history of St Benet Hulme suggests that he spent more time at the University than in the cloisters: by 1526, some of the monks thought the community was becoming slack, although the most specific complaint was the presence of too many dogs.[80] By this time, Capon – like Audley – had become an adherent of Wolsey, but both men side-stepped the Cardinal's fall and energetically championed the king's plans to divorce Catherine of Aragon. This renewed Capon's links with Cambridge, where he was chosen as a member of a University commission ostensibly intended to study the validity of the marriage, but – of course – actually established as part of Henry VIII's propaganda machine.

In 1534, Capon was appointed to the see of Bangor in north Wales, although he held the bishopric for just five years. He was by now deeply committed to the cause of religious reform, but was mainly based in London. He appointed his brother as his diocesan administrator, but it is unlikely that the Master of Jesus spent much time in Wales either. Nor would they have achieved much had they actually visited: Capon admitted in 1535 that he was hampered in the "diligent setting forth and sincere preaching" of Protestant ideas by his inability to speak Welsh.[81] The clergy of the Bangor diocese were not noted for learning, and it is likely that Capon relied upon two educated cathedral officials, Robert Evans, who became Dean in 1534, and John Hughes, a member of the chapter who held various parish appointments. We may be reasonably sure that both spoke Welsh as their first language, and were capable of acting as intermediaries between their bishop and his flock. Hughes we have already encountered as the real founder of Magdalene; Evans would be appointed as the College's first Master, retaining his Deanery plus, incidentally, a very lucrative living in the Fens. In 1539, Capon was translated to Salisbury, where he would crown twenty years of energetic support for the Reformation by presiding over the burning of heretics during the reign of Mary.[82] In John Capon, we have the combination of factors that point to a supporting role in the establishment of Magdalene: episcopal status, political skill, association with Cambridge, all capable of working through plausible links with both Audley and Hughes. It is likely that he was in or around London in the early months of 1542, when the letters patent were issued, for he was commissioned by Convocation to contribute to a planned (but abandoned) project for a new translation of the Bible. Capon was allocated the epistles to the Corinthians. How he would have handled the inspirational evocation of charity in 1 Corinthians 13 we can only guess. The family surname was occasionally spelt "Capone", and the variant seems somehow appropriate.

If Capon was indeed a key player in the refoundation, his role underlines the extent to which the project was linked to north Wales, and the diocese of Bangor in particular. The most traditional part of the Principality, the area was doggedly Catholic and overwhelmingly Welsh-speaking, served by clergy who were generally poor, uneducated and firmly attached to their womenfolk. Capon's attempt to make them dump their concubines (as their blameless partners were cruelly termed) triggered a petition to Thomas Cromwell in 1536, in which they argued that, deprived of their female companions, they would be banned from the homes of laity because they would be perceived as a threat to the chastity of wives and daughters. Nor could the region be written off as an unimportant backwater. Not only had it been the centre of resistance to English rule in the time of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in the thirteenth century, and Owain Glyndŵr in the fifteenth, but Anglesey in particular was regarded as strategically vulnerable, open to seizure by both the Spanish and the Scots. In 1542, Capon's successor enjoined his clergy to give religious teaching to their parishioners in Welsh, but it was not until 1547 that a Welsh primer appeared – the first printed book in any Celtic language, and even then a private project rather than a government initiative.[83] Education was clearly the key to producing Welsh clergy capable of translating English and Protestant ideas to their flocks, and thereby making them loyal and peaceable subjects. It is likely that there was something more than the rescuing of a stranded academic hostel at stake in the launching of Magdalene.

It is reasonable to suggest that a coalition of interested parties around Thomas Audley pointed him towards the rescue of a destitute academic unit, but it would be implausible to assume that so masterful a personality was manipulated as a simple cipher. Audley's own motives are of some importance, not least in relation to the name he selected for the revived institution. We may begin by dismissing one charming tradition, that he had studied at Buckingham College and was paying some debt of gratitude. There is some slight evidence that the Benedictines took in students who were not monks – or perhaps simply rented vacant rooms to balance the books – but it has proved very difficult to identify any of them. Although he was about 22 when he was admitted to study at the Inner Temple in 1510, old enough to have allowed for a preliminary sojourn at university, the available evidence seems to indicate that he opted for a professional training, sufficient to qualify him for the office of town clerk of Colchester just four years later. Audley mocked the intellectualism of Sir Thomas More, telling More's daughter: "I am very glad that I have no learning but in a few of Aesop's fables". The French ambassador sneered that Audley could not converse in Latin, a requirement of Cambridge students, although the ferocity of such provision in various statutes suggests that it was not always observed.[84]

J. B. Mullinger, a nineteenth-century historian of the University, made the reasonable deduction that Audley's interest in Buckingham College stemmed from his acquisition in 1538 of the Benedictine Walden Abbey. However, Mullinger dived too deeply into the romantic when he hazarded that "the Cam itself, as it stole onward through the abbey grounds at Walden, might serve to remind him of those ancient and impoverished foundations which rose on its banks in its remoter course".[85] It is much more likely that Audley's interest was aroused on learning that Walden Abbey had constructed one of the staircases when Buckingham College had launched into bricks and mortar. The abbey would certainly have asserted at least a moral claim to the occupation of the chambers it had erected, and Audley's covetous legal mind would have translated that into some form of property right. Although Walden Abbey would have exercised at most a consultative role in the Order's selection of the head of the hostel, Audley was obviously attracted by the patronage power of an external appointment, implicitly using the monkish precedent to reserve the choice of Master of Magdalene to himself and his heirs. The prior studentium cast a long shadow over the College until the increasingly inappropriate provision was finally abolished in 2012.

Another major development in Audley's life that occurred in 1538 was his elevation to the peerage, as Baron Audley of Walden. His new status involved the acquisition of a coat of arms, often an opportunity for a new man to claim fake aristocratic ancestry. A medieval Staffordshire landowning family called Audley were an obvious target, but there were no clues or connections that might have justified resort to the common practice of buying a spurious genealogy from the College of Heralds. Audley's father seems to have been a land agent managing an estate near Colchester, and their surname was generally spelt "Audeley". Thomas could do no more than hint at some association: he dropped the middle letter, and incorporated the Audley knot, the Midlands family's geometrical symbol, into his own coat of arms.[86] The medieval family had been granted several peerages, one of which passed in the fifteenth century through the female line to the Buckinghams. The title had gone into abeyance at the fall of the third Duke. Taking control of the destiny of Buckingham College was another way of signalling a claim to noble ancestry, unstated (because not susceptible of proof) but artfully projected.[87] Thus there were certainly elements of vanity among Audley's motives, and it may be for the best that this was so. The Dissolution hit University enrolments hard, and there was no student demand that might have justified the founding of another college in 1542.

No amount of historical revisionism will ever succeed in portraying Thomas Audley as anything other than hard-nosed and hard-hearted. Yet there is one curious episode which may throw light on his involvement in the Magdalene project. Visiting his home in Colchester in September 1538, he had learned of rumours that the town's Benedictine abbey, St John's, and the Augustinian house at St Osyth, ten miles away, on the coast, were both facing closure. He was probably lobbied by the abbot of St John's, Thomas Beche, whose vocal defence of his community would take him to the gallows a year later. Since he had, six months earlier, accepted the grant of Walden Abbey, Audley was not an obvious ally in the fight against dissolution.[88] He had used Colchester to launch himself into national politics as MP for the town in the parliament of 1523, but he no longer needed his home town as a power base: Colchester was economically stagnant, and it needed Audley's support rather than vice-versa. Nonetheless, he sent a curious proposal to Thomas Cromwell, arguing for "the contynuance of the same ii places, not as they bee religious, but that it mought pleese the kynges majesty of his goodness to translate them into colleges".[89] Audley was entirely happy for Henry VIII to determine what form these institutions should take, and for the appointment of deans and prebendaries to become a royal prerogative. Since he was prepared to pay the staggering sum of two thousand pounds to preserve the two monasteries, Audley evidently wanted to save them very much. Yet his fervent plea suggests that he was not very clear in his own mind why they should be exempted from the general assault on monasticism. He argued that Colchester contained "many poor people which have daily relefe of the house; another cawse, bothe these houses be in the ende of the shire of Essex where litel hospitality shalbe kept yf these be dissolved ". These were standard arguments in defence of all religious houses, with no serious reason advanced to justify their particular use here. Few travellers were likely to be inconvenienced by the closure of the two abbeys: Colchester was a large town well supplied with inns, while St Osyth was located at the end of a peninsula where few wayfarers would have passed.[90] Audley added that "Seynt Jones lakkyth water and Seynt Osyes stondith in the marshes not very holsom as yt fewe of reputation as I thinke will kepe contynual howses in any of them save it be a congregation as ther be now". (In fact, both abbeys later became great houses.) He also threw in the plea that there were " xxti howses gret and small dissolved in the shire of Essex all redy". Indeed, Audley seems to have appreciated that he was not making a very strong case, urging Cromwell that "knowyng bothe the howses as ye do can alegge more better considerations than I can imagyne or wryte".

It is difficult to imagine how Audley's vaguely conceived colleges would have differed from the monasteries they were supposed to replace (which may have been the idea). He was not totally alone in his fantasy: Bishop Latimer similarly sought to carry forward the priory at Great Malvern "not in monkery", but as a centre of "teaching, preaching, [and] study with praying".[91] In deepest Worcestershire, that might have been a safe endeavour. But Colchester was a town with a stubborn Lollard tradition, and a maritime trade around the North Sea, elements that would surely have encouraged a fermentation of Lutheran ideas. A case might have been made for the conversion of St John's into a cathedral, with an accompanying chapter – Colchester had been designated as the title for a suffragan bishopric in 1536, but that was a roving commission that did not require an episcopal headquarters. The creation of new dioceses did not come on to the political agenda until the following year, and Audley would perhaps have rejected the strategy as requiring the abandonment of St Osyth. Not surprisingly, this bizarre exercise in spiritual nimbyism quickly disappeared. After making the tactical mistake of denying that the king had any right to close his monastery, Abbot John Beche was arrested for treason in November 1538, the same month in which Audley was awarded his peerage. Nonetheless, Thomas Audley did secure one small success for Colchester and for the cause of education. In November 1539, Henry VIII granted the property of two local chantries to the town, for the erection of a free school to be governed by statutes and ordinances – to be laid down by Audley himself.[92] As with Magdalene, he had not got around to this detailed work by the time of his death in 1544, but it seems clear that Thomas Audley was open to backing educational projects, provided somebody else's resources could be mobilised for his own glorification. When, just over two years later, a coalition of associates and acolytes pressed him to establish a college at Cambridge, he was willing to listen. The practical mechanics of chartering Magdalene were straightforward, for letters patent were promulgated in the king's name by the Lord Chancellor. Since this was the office that Audley held, in effect he simply wrote his own ticket. This gave him unlimited scope to choose a name for the new institution.

M+Audley+N Both the letters patent of 1542 and the original Statutes of 1555 were in Latin, but it is reasonably certain that the founder intended to rename Buckingham College as the College of St Mary Magdalene in the University of Cambridge.[93] However, we can be reasonably sure that name "Magdalene" was the keyword, in whatever spelling, and that it was pronounced to rhyme with "dawdlin'".[94] In 1655, Thomas Fuller offered an ingenious interpretation of its derivation, which he indicated was in general circulation ("as some will have it"). Audley had chosen to honour the Biblical saint because "his sirname [sic] is therein contained, betwixt the initial and final letter thereof, M AUDLEY N."[95] Fuller, a student in the 1630s, would have encountered dons whose origins were close to the founder's era, which lends credibility to a plausible tale. However, the story dropped from sight, perhaps because it did nothing to enhance the collective self-esteem of an institution that was already the Cinderella of Cambridge. Neither Clark nor Purnell even considered the possibility. It seems to have been revived by Arthur Gray of Jesus College, who produced an enviable output of good-humoured Cambridge history in the early twentieth century – but even Gray assumed Fuller was being facetious.[96] However, A.C. Benson, himself a skilled wordsmith, picked up the idea in 1923, and called it "probable".[97] The hypothesis is now generally accepted. Noting that many early documents in the College archives used the spelling "Maudleyn", Cunich concludes that the choice "seems to have been act of clever arrogance by Audley".[98]

Perhaps we should not jump to the conclusion that the pun was merely a piece of insensitive boasting. Audley was content to act as assiduous chief messenger rather than powerful chief minister to Henry VIII, but he would have been well aware that two of his predecessors, Wolsey and Cromwell, had dramatically fallen from favour because, as men of humble origins, they had antagonised the traditional nobility by displaying overweening pride. Thomas Audley would have been well advised to tread a careful line – pride at his rise in the world was pardonable, arrogance could be counter-productive. Hence we should ask: were there other layers of meaning in the choice the new collegiate name? Here, a loud note of caution is required. Grafting Tudor thought patterns on to my mental universe, formed four centuries later, may be like seeking to reverse extinction by injecting dinosaur DNA into a hedgehog. The process can generate results, but it also risks producing monsters. Even E.M.W. Tillyard, who memorably explored the world of Shakespeare's contemporaries, warned his readers that there were "many variations about the way the universe was constituted" and that some of his interpretations were "only approximate".[99] My own speculations certainly call for ferocious interrogation by experts in the period. Nonetheless, it may be confidently stated that letters and wordplay conveyed important (if sometimes conflicting) messages to contemporaries. Nor should we forget that colleges spent a great deal of time at prayer. Some at least of these services would have been accompanied by homilies and sermons, and preachers presumably sought ingenious new angles to vaunt the merits of their founder and their patron saint.[100]

One problem in the religious use of letters was that the major examples came from the Greek alphabet, which presumably limited popular interpretations of their significance. Thus the Christogram, IHS, represented the first three letters of the name of Jesus, the H being the Greek long E (eta).[101] Probably more widely understood was the pairing of Alpha and Omega, the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet, to convey the concept of the eternity of God. The official promulgation of the Great Bible of 1539 would have made its meaning clearer to those churchgoers who ventured into the imagery of the Book of Revelation.[102]