Terling images: towards a reconsideration of the 'Terling thesis'

This file forms part of preparation for a re-consideration of the 'Terling thesis', the findings in Poverty and Piety in an English Village [PPEV], a study of the Essex parish of Terling from 1525 to 1700 by Keith Wrightson and David Levine. This preliminary study seeks to explore and reconstruct the Terling of c.1600. It argues that a distinction should be drawn between the wider parish and the actual village. It also emphasises that the latter was dominated by a very large mansion belonging to one of the county's leading families, and that an active (in some cases, over-active) inn, the Angel, stood at its centre. An alternative explanation for campaigns against social disorder in the early seventeenth century, one that stresses gentry control, is advanced in "The Terling thesis: an agenda for the reconsideration of the work of Wrightson and Levine" https://www.gedmartin.net/martinalia-mainmenu-3/345-the-terling-thesis.

(PPEV was published in 1979, but reissued with a supplementary essay by Wrightson in 1995.) In an impressive reconstruction of local society, Wrightson and Levine supply much information about a broad range of subjects, such as kinship, literacy and Puritanism. As an enthusiast for Essex local history, my concern is that they use the terms 'village' and 'parish' interchangeably, sometimes creating the impression that all events occurred within the compacted area that most readers will associate with the term 'village'. I argue that no more than half the population of the parish lived in Terling village, with the remainder distributed over the relatively broad area of the wider parish, and that this distribution has implications for the interpretation of local events. I suggest also that the Wrightson and Levine discussion obscures the presence – unusually, on the fringe of the village – of a large mansion inhabited by members of the Mildmay family, one of the most influential gentry clans in late sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Essex. Full references and supporting evidence are supplied in the essay "The Terling thesis: an agenda for the reconsideration of the work of Wrightson and Levine" (https://www.gedmartin.net/martinalia-mainmenu-3/345-the-terling-thesis) that accompanies this commentary. Sources used include C.A. Barton, Historical Notes and Records of the Parish of Terling (1953) and Essex Archives Online (formerly Seax). Barton's book was a compilation of sources which often provide clues to documents worth following up. His extracts from the parish registers, although chosen more or less at random, provide useful but far from comprehensive information. Essex Archives Online is a calendar of documents in the Essex Record Office, which provides more information on some items than others. My intention in this presentation and the accompanying essay is to suggest an agenda for the reconsideration of the conclusions of Wrightson and Levine which I hope other scholars may wish to pursue.

This introduction to the village and the five square miles of the parish of Terling is based upon photographs by David Mills, and by sketch maps, superbly drawn from my scrawled drafts by Bernard Cope. My warm thanks to both for their help. I am also grateful to Heather Cutler of Historic Terling for patiently responding to my uninformed questions. The buildings illustrated here are, of course, privately owned and not accessible to the public.

Terling in Essex: location and landscape

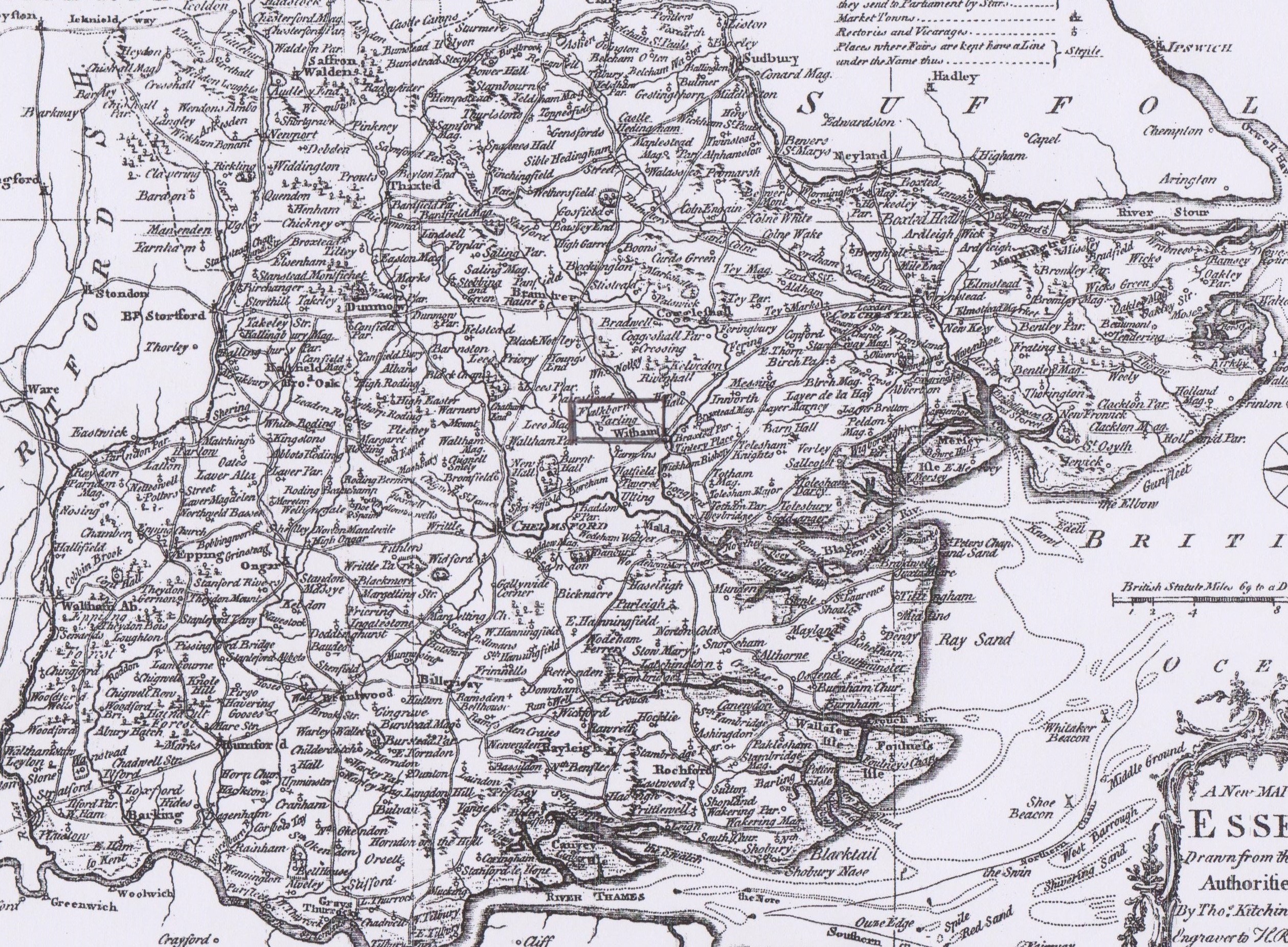

Terling [boxed] is located right in the centre of the county, shown on this map of 1764 under its dialect name, Tarling. Wrightson and Levine estimate that the population of Terling rose from about 330 in 1525 to approximately 580 by 1671. They calculate that the bulk of this increase happened before 1625. Population pressure may have contributed to an increased emphasis upon social control around 1620.

Terling: landscape

Terling is located on fertile Boulder Clay. Although its farmland seems empty today, prior to the 19th century, the need for farm labour meant that outlying parts of the parish were well populated. Its thriving agriculture implied close links with markets.

Terling: the local area

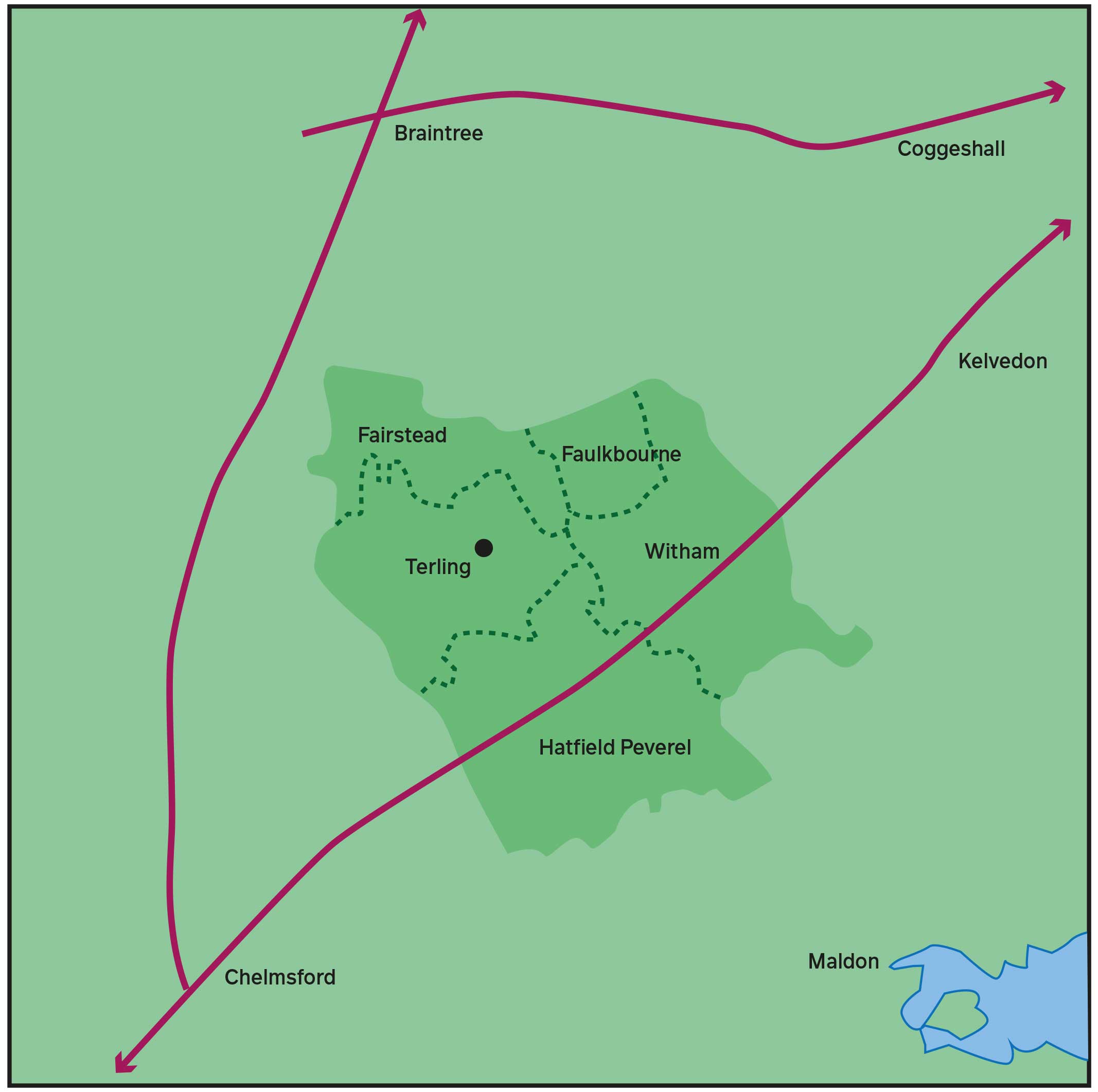

This map demonstrates three points: [1]. Terling was located close to a number of (generally) thriving market towns. Witham, the closest, is 3 miles from Terling village. These towns had varying economic bases: Braintree in particular was a weaving centre (as were Coggeshall, Kelvedon and – to some extent – Witham). Chelmsford was an administrative centre, the seat of the county courts and an important link to London, with its explosion of consumers in the 16th and 17th centuries. Maldon was a port, a source of fish and – increasingly important in the local economy – of coal, as well as an outlet for bulk produce shipped to London and across the North Sea to Flanders.

[2]. Terling had the advantage of proximity to major highways, but was to some extent shielded from the problems associated with main roads: Witham, for instance, had problems when Irish soldiers were billeted on the town in 1628, and suffered several outbreaks of plague between 1638 and 1641. However, Terling was not entirely exempt from health and social challenges: about one twelfth of the population died of plague in 1625, and almost one eighth during further outbreaks in 1663-4. Nor was Terling too remote to attract wayfarers: between 1565 and 1597, the parish register records the burials of five indigent wayfarers, doubtless an indication of a far larger number of beggars and drifters. Terling attracted some implausible visitors: in 1678, parish officials gave money to three shipwrecked sailors, and in 1683 they were called upon to help twelve flood victims passing through from Lincolnshire.

[3]. A sample of parish boundaries shows the inter-relationship of Terling with Fairstead, Faulkbourne, Hatfield Peverel and Witham. Using the concept of a 'social area', Wrightson and Levine demonstrate that Terling people had various forms of interaction with residents of neighbouring communities, but they also insist that "Terling had its own integrity as a social unit". Prior to the secession of a substantial number of Dissenters after the Civil War period, the parish functioned effectively as an ecclesiastic unit. In 1630, the parish constable reported that everybody attended church, while a rare backslider that year ingeniously pleaded that "he could not get into the church by reason of the crowde of people". (Pressure of numbers may be explained by an incursion of strict believers from Witham, several of whom were prosecuted in 1631-2 for attending worship in Terling instead of at their own parish church. They were drawn by the preaching of the controversial Puritan vicar Thomas Weld, who soon afterwards was forced to flee Laud's anger and seek refuge in New England.) The parish also operated with outline efficiency as an administrative unit, although this probably directly affected a much smaller number of local worthies who were compelled to accept various unpaid responsibilities, as churchwardens, overseers of the poor and jurors reporting to the local courts.

However, the parish almost certainly operated as much less of a closed community for social and economic purposes. Wrightson and Levine identified 72 Terling people who found marriage partners outside the community, and there were probably others not noted in the parish registers (or who married elsewhere). The economic importance of nearby market towns and manifold business activities of their residents have been underlined since the publication of PPEV by the detailed research of Hilda Grieve (on Chelmsford), Janet Gyford (on Witham) and W.J. Petchey (on Maldon). Witham, only three miles away from Terling village (and, of course, much closer to the south-eastern fringe of the parish), may be assumed to have been of considerable importance, even though Terling people left relatively few traces in its records. In 1722, Daniel Defoe called it "a pleasant, well-situated market town", while to White's Directory of 1848, published just five years after the arrival of the railway, Witham was "small, but handsome and well-built". To take one example, when specialised work was required to renew the windows of Terling's parish church in 1668, it was a glazier from Witham who undertook the work. It should also be pointed out that Fairstead and Faulkbourne were parishes with no village centre and small populations: in 1650, it was reported that Faulkbourne had "not above twelve ffamelyes ... some farre remote from the parish church". Fairstead and Faulkbourne were perhaps not very obvious to the Terling community, but Terling was important to them. (In the mid-seventeenth century, one rector of Fairstead kept a tithe notebook in which he made "a note of what ground Terling men hold in Fairstead" and also listed "what ground our townsmen [parishioners] hold in Terling".) In "The Terling thesis: an agenda for reconsideration", I argue that an understanding of Wrightson and Levine's valuable research into the social area may be deepened, first, by examining the capabilities and functions of nearby parishes, some of which were probably too small to function as independent communities and, second, by appreciating the distinction between the conglomeration of Terling village and the more scattered population of the wider parish, the latter tending to meld into a wider population area. This approach would be in line with the conclusion advanced by Wrightson and Levine themselves: "In dealing with social mobility, the appropriate unit would be Terling's full social area rather than the parish itself."

Terling: parish and village

The parish of Terling

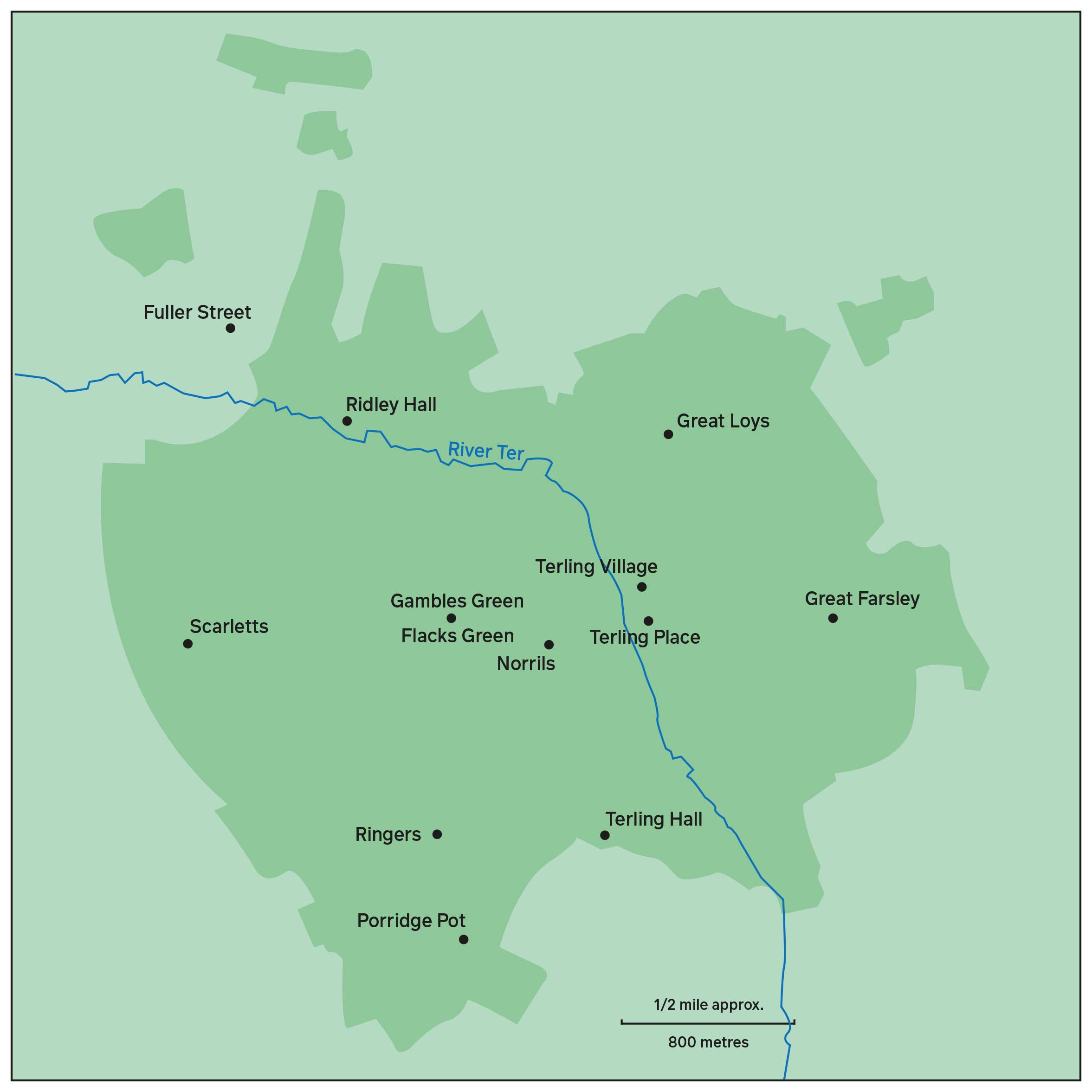

This map of the parish of Terling shows the village and the Strutt family mansion of Terling Place, the latter – as already noted – not built until 1772-3. A scattering of buildings three-quarters of a mile west of the village at Flacks Green and Gambles Green (names not in use before the late eighteenth century) formed a second, and probably smaller, concentration of population.

Other points noted are Fuller Street, a hamlet in Fairstead which probably depended upon Terling for some services, the Rochester family mansion at Great Loyes (later, according to local tradition, reduced to a farmhouse), Norrells (also called Norrils), the home of Augustine Norrell, regarded by Wrightson and Levine as a village leader in the push for reformation of manners around 1620, Porridge Pot (also called Great Hooks), Ridley Hall, Ringers, Scarletts and Terling Hall (also known as Margeries). Great Farsley, Porridge Pot, Ringers and Scarletts owed their names to medieval owners. Ridley Hall was Retleia in Domesday Book.

As noted, Wrightson and Levine use the terms 'village' and 'parish' interchangeably. Sometimes they imply that all Terling people lived in the village: "The villagers lived and worked in close proximity to one another. ... The village was riddled with petty conflicts." PPEV has no map of the parish: this sketch map seeks to fill the gap. Estimates of the area of the parish in the 19th century vary from 3056 acres to 3228 acres – the latter amounting to almost exactly five square miles. While Terling parish may look like a reasonably coherent unit on the map, it perhaps seemed less so to its inhabitants who were required to conduct an annual "perambulation" to check boundary markers. A detailed account of 1770 listed 148 points where the parish boundary changed direction, including several illogical projections, such as the narrow 'fingers' of fields extending north near the Fairstead hamlet of Fuller Street. In addition, there were four detached portions, transferred to Fairstead in the eighteen-eighties, although only one of these seems to have been inhabited by the nineteenth century. "The Terling thesis: an agenda for reconsideration" will argue that around 1600 the village probably contained no more than 250 people. This estimate is based on a map of part of the parish surveyed in 1597 by the Walkers of Hanningfield, pioneer Essex cartographers, who carefully incorporated thumbnail sketches of buildings. (The map, in private ownership, is known through photographs of a faded original.) These thumbnails make it possible to estimate the respective populations of the village and the wider parish, although damage over the centuries has made it difficult to decipher the information with complete confidence. In 1994, two distinguished archivists from the Essex Record Office, K.C. Newton and A.C. Edwards, published a colour photograph of the village area, and also provided an analysis of building types across the rest of the map. This information seems to suggest that less than half the population of the parish lived in the village area. Some residents in the wider parish lived over a mile away: the Hare family, who appear as local notables in PPEV, farmed at Scarletts, a distance of almost two miles. Farms on the eastern side of the parish, such as Great Farsley, may have found it more convenient to do business in the busy town of Witham.

Recognition of a distinction between the village and the wider parish has two major implications. First, the kind of crime that happens where people dwell in close proximity is likely to be different from offences in remoter areas: interpersonal clashes can indeed be petty and result in unplanned explosions of conflict within the relatively confined space of a village, but those who live in isolated homesteads are more at risk of organised attacks. The dominant gentry family in Terling until 1618, the Rochesters (pronounced, it seems, Rowchester) were inclined to resort to strong-arm methods to deal with rent arrears or to resolve disputed property claims. One of Terling's most violent episodes, a dispute within the family, happened in 1581 on property at Great Loyes, about half a mile north of the village. Second, farms located at some distance from the village were likely to have economic ties with other parishes: the front windows of Terling Hall to the south actually looked out into Hatfield Peverel, Ridley Hall in the north was for a time the property of the owners of New Hall, Boreham. The Powersend property in Witham parish extended across the Terling border. Similarly, although William Rochester, who died in 1584, was based at Great Loyes at the northern end of the parish, he also owned land in Hatfield Peverel, to the south, and at Ulting, six miles down the Blackwater valley, and also had business interests in Maldon.

Flacks Green

Flacks Green is one of two adjacent scatterings of houses three-quarters of a mile west of the village.

The surname Flack does not seem to have appeared in Terling until the 18th century, and the earliest example of the name Flacks Green I have noted dates from 1778. I do not know what the hamlet was called at any earlier time. (Parts of it were also known at various times as Simon Collins Green and Stokes Green.) There was a beerhouse at Flacks Green in 1851. Its landlord was described as a maltster (i.e. brewer), which could suggest a long-established business. A blacksmith and a wheelwright also operated at Flacks Green in the mid-nineteenth century.

Gambles Green

As with Flacks Green, I do not know the 17th-century name of nearby Gambles Green. (Barton implies that the two greens were known as the Tyes.) The number of surviving buildings from that period at both places suggests that it would be unwise to assume that all Terling alehouses were located in the village, but further and more detailed research would be needed to establish whether there were shops or other services at the two greens. The 1851 census listed just over 100 people at the two Greens. Given that the population (900) was 1.55 times larger than Wrightson and Levine estimate for 1620, this might point to 70 people living there in the seventeenth century.

There was a further scatter of buildings, of which five survive from pre-1700, about 500 yards north of the village at Owls Hill. In the early seventeenth century, there might have been 30 to 40 people living here. Owls Hill was incorporated into an expanded village area after 1850.

To complicate further the picture, the apposition between core and periphery was not the only internally divisive element in the parish. Terling's river may not look impressive on any map, but it tended to create a barrier between east and west.

The river Ter

In 1953, the local historian C.A. Barton noted that communications between the east and west of the parish had always been poor, thanks to the river Ter. (The name is a back-formation from Terling, and there is no evidence that it was used before the 19th century.) Norman Bridge, shown here, is about 600 yards north-west of the village. There may have been a bridge for carts in the sixteenth century (the bridge was reported to be "broken and in great decay" in 1574, when a local landowner offered to contribute one tree for its repair) but (unsuccessful) local pressure for a brick bridge in 1829 suggests that there was then only a footbridge, as is the case today. (The Ordnance Survey map shows two other footbridges in the area of Ridley Hall upstream, and Google Satellite indicates a ford.) As the depth marker indicates, even when there is relatively little water in the Ter, it can still be a hazard: a twenty-first century road sign advises that the ford is unsuitable for motor vehicles. A Fairstead child was drowned here in 1660. Prior to the closure of the road from the village to Boreham in 1771, there seem to have been only two bridges over the Ter capable of carrying vehicles, and long stretches, especially downstream from the village, that lacked safe crossing points of any kind. It is likely that the river created divisions between the east and west of the parish: Barton mentioned that the parish elected two surveyors of highways in the seventeenth century. In the seventeenth century, there was a water mill at Terling Bridge, close to the village. Its mill race was also a hazard, and its dam probably raised the river level in the northern part of the parish: in 1596, two children were drowned just upstream, and the body of another victim was recovered from the river "near Tearlinge Mill" in 1602.

Recovering the 17th-century village

In 1772-3, the wealthy Strutt family built Terling Place, a little to the south of the village. Forty years later, the family acquired a peerage. The third Baron Rayleigh was a distinguished scientist and, with his brother the Honourable E.C. Strutt, promoter of large-scale commercial farming, with an emphasis upon dairying. In 2021, 250 years later, Terling Place remains one of the few country houses in Essex still occupied by the family who originally built it.

Terling Place: the mansion of 1772-3

This cameo from an 1832 print by Bartlett shows the idealised landscape of the park. The spire of the parish church forms part of the backdrop, but the village itself was not a must-have accessory.

John Strutt had purchased Terling Place – the former Mildmay mansion, discussed below – in 1761, and moved there four years later. He had no knighthood or title (indeed, he is said to have refused a baronetcy), but he was enormously wealthy. He quickly became dissatisfied with the accommodation reserved to the Big House in the parish church, but his proposal in 1765 to reconstruct and extend the Strutt family pew no doubt displaced other parishioners and probably had a knock-on effect across the seating arrangements of the entire congregation. He had his way, but whoever noted John Strutt's victory in the parish records obviously resented his pretensions, noting that he "will Pew in the Church according to his own likeing at his own likeing at his own charge". (The following year, Strutt's accounts showed a payment of £256 and eighteen shillings for "improvements" to the church: the equivalent of over £40,000 in 2021 values.) When the new mansion was built in 1772-3, the southern end of the existing village was cleared to make way for it. The road which led to the market town of Witham and Hatfield Peverel, 1,110 yards in length, was diverted to the east. A road leading south-west towards Boreham was closed to the public altogether. These substantial changes in the local highway network were obligingly approved by a special magistrates' hearing held "at the owner's house in the parish of Terling".

Viewed from Hatfield Road looking west, a line of trees marks the track that was part of the 1771 highway diversion. It was probably closed to the public in 1788, and certainly ceased to be a right of way after 1850.

Further changes, involving the clearance of tenements, formed part of the "improvements" carried out by the second Lord Rayleigh between 1845 and 1850. To understand Terling in the 17th century, it is necessary to reconstruct the village and parish before the arrival of the Strutt / Rayleigh family and the building of their handsome Georgian mansion. This exploration of the lost village is undertaken in reverse order. The modern village centre is the product of the reorganisation of 1845-50. It seems best to start with this as a stepping-stone back to the seventeenth century.

Terling village in 1844

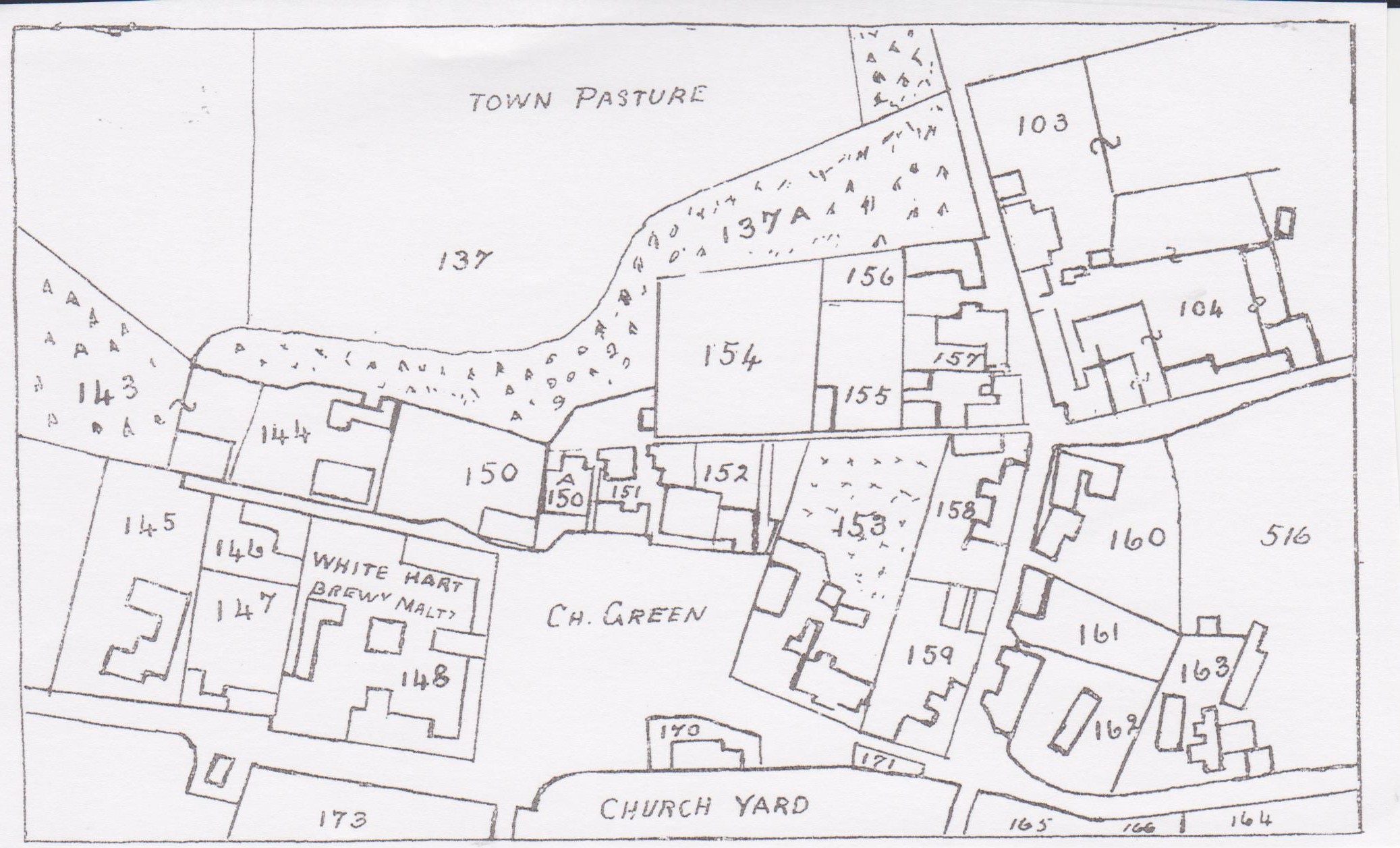

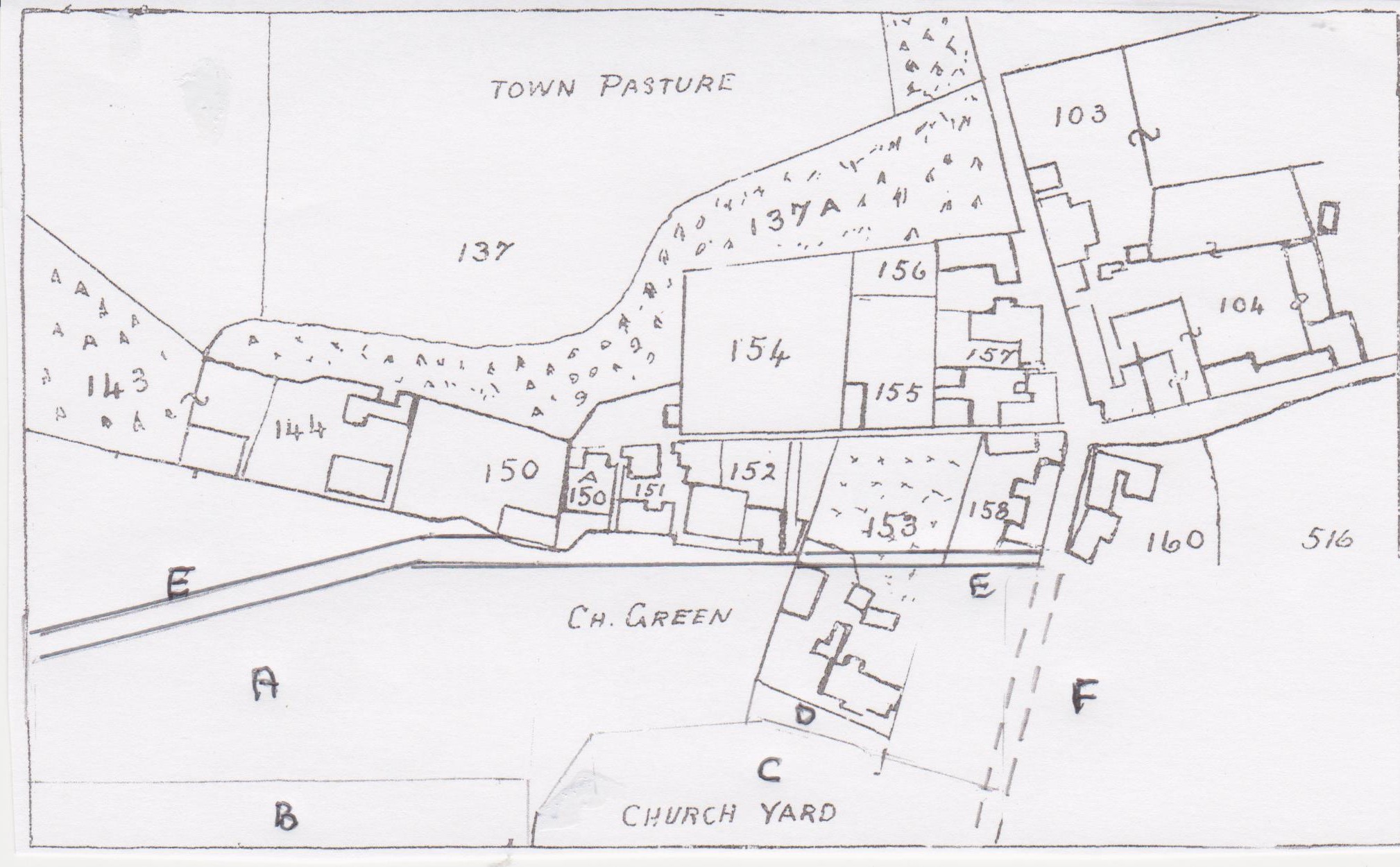

This plan of the village is an inset from the tithe commutation map, reproduced in C.A. Barton's 1953 local history volume. The numbers refer to the accompanying survey (text and maps reproduced in James Kemble, The Place Names of Terling, 2010, available via www.essex.ac.uk/history/esah/essexplacenames).

The map was dated 1844, although the tithe commmutation, which transmuted into cash payments the obligation to supply the Church with one-tenth of all produce, was agreed in 1841-2. Perhaps the most obvious feature is that the Green is surrounded by buildings, whereas nowadays it is open to the west, sloping down to the river Ter, the site in earlier times of the watermill. The Street, which runs north to south, was lined by buildings alongside The Tudor House (153), a section that now forms part of the private drive into the grounds of the mansion. Building no. 161, described as a tenement, was occupied by John Harris, the village blacksmith. In December 1845, Lord Rayleigh informed the Vestry that he had opened a school for boys "to keep them from loitering about the streets, and congregating for gossip at the Blacksmith's Shops". Also worth noting are building 150A, the Congregational Chapel built in 1753 and closed in 2017, and 152, the Tabor house, discussed below. Mill Street runs east-west along the foot of the map. Access was obviously difficult at the pinch-point caused by building 171, a cottage adjoining the churchyard. The continuation of this road to the east represented part of the diversion arranged by the Strutt family in 1771. Plots 164-6 were gardens let to local residents. But downtown Terling was on the eve of major changes.

Terling village after c.1850

The White Hart was still in business in 1848, when John Smith was listed in White's Directory of Essex as the landlord. However, soon after, it was replaced by a new hostelry, the Rayleigh Arms, located on a generously spaced site at Owls Hill, several hundred yards to the north. This is first mentioned in the Chelmsford Chronicle on 17 May 1850, and Smith was listed in the 1851 census at the new establishment. The redesign of the village was the work of the second Baron Rayleigh, who had moved into Terling Place in May 1845 after the death of his father: "the event produced quite a holiday among the inhabitants and joyous villagers. ... the hearts of the poor were made glad; and the booming of cannon welcomed the noble lord and his lady to the family seat." (Lord Rayleigh's father had spent the last four years of his life as an invalid at Bath: as the Honourable Charles Strutt put it, "the villagers ... had perhaps discovered the disadvantages of absentee landlordship in the interregnum." A resident squire, particularly one keeping up the splendid dignity of a peerage, meant that cash would be spent.) Lord Rayleigh set about a programme of "improvements", thoughtfully – so he explained – employing workmen from other villages at low wage rates, so that he would not undercut the local labour supply of Terling rustics toiling for Terling farmers. One clue that helps explain the relocation of the White Hart may probably be found in the fact that it brewed its own ale: breweries and maltings generated pungent odours that would have become objectionable to genteel Victorian nostrils. Census returns for 1851 and 1861 indicate that landlord Smith continued to brew his own beer, but now at a discreet distance from the Big House. (The Honourable Charles Strutt, in his privately printed family history, thought the clearances were made "about 1832", but this may refer to the date when the properties were acquired: the evidence from the 1844 tithe commmutation map is conclusive.)

[A] marks the site of the White Hart and nearby tenements, cleared away to form part of the Green. [B] indicates the edge of the Terling Place grounds, here a plantation of trees screening the house and associated buildings from passers-by. [C] shows the churchyard extended to the north across the former line of Mill Street. In earlier times, burial on the north side of the church was associated with unbaptised infants, suicides and executed criminals. However, by the mid-nineteenth century, population pressure pushed such concerns aside: like most parishes, Terling evidently required more burial space. Lord Rayleigh agreed in 1853 to construct a fence along the new northern boundary (the parish paid). Sensibly, the end product was a wall – decorated with the flintstones in Victorian fashion – a necessary device since burials raised the level of graveyards. [D] indicates the closure of Mill Street in front of the Tudor House, where the line of the old roadway may still be seen as a lawn. It was replaced by a new link, Church Road (marked as [E]), cut through the former garden of the Tudor House. [F] records the clearance of the southern end of The Street, which became part of the private drive to the mansion. Among several tenements removed was the former Angel Inn (probably already long since closed) and the blacksmith's shop that Lord Rayleigh had criticised in 1845: the 1851 census shows that John Harris had also been relocated to Owls Hill. The roadway to the east, leading to Witham and opened as part of the 1771 highway changes, was presumably closed at this time, and may indeed have been diverted again as early as 1788.

I have not traced any administrative approval, for instance at county level, for the road closures, although no doubt some formalities were observed. It was an era when the prestige of a member of the House of Lords, especially at local level, was enormous, and this may explain why the local press made no mention of the undoubtedly newsworthy story that villagers were being relocated from their homes because their presence was unpalatable to the Big House. Lord Rayleigh's authority was disguised within a culture of paternalism. One highlight of the year was the annual Christmas ceremony, at which Lord and Lady Rayleigh gave beef, bread and clothing to the poor of Terling and Fairstead. In 1847, there were 858 recipients: in 1841, the combined population of the two parishes had been 1,227. In 1851, the parents were assisted by "the young heir of the house, the Hon. Mr Strutt" – he was eight years old – who joined "gladsomely" in the distribution, heartening evidence that "this benevolence is sure to be hereditary". As the third Baron Rayleigh, the young heir would go on to win the Nobel Prize for the discovery of argon, the result of extensive experiments in a specially constructed facility at Terling Place, or – as one gamekeeper memorably put it – "his lordship spend most of his time in his lavatory". Paternalism was a polite weapon for the enforcement of social control. When he presented prizes at a school fete in the summer of 1849, Lord Rayleigh added "some appropriate observation and advice" to each tiny recipient. With the assistance of helpful tenantry, the "little ones" were fed on roast beef and plum pudding. A local clergyman praised "his lordship's uniform kindness and generosity", and the proceedings closed with the children giving three cheers for their host and hostess.

It was a strategy that could be applied on a wider canvas than Terling. In August 1848, Lord Rayleigh chaired a public meeting in Chelmsford to raise money for "the education and religious instruction of the native Irish in the vernacular tongue" – although, with the country in the grip of the potato famine, perhaps some assistance in the provision of food would have been more helpful. Half a century later, a movement for the revival of Ireland's Gaelic language would constitute a driving force in a radical new form of nationalism. However, the aim here was to assist "in disseminating those truths which would exert a most pacific influence over the inhabitants of the sister isle, in its present disturbed and agitated condition." In other words, if the Irish could be educated to become Protestants, they would cease to be a problem. Even though attendance at the meeting was "very thin" (perhaps not a surprise) the Chelmsford Chronicle thought the event worthy a deferential report, in marked contrast to its silence about Lord Rayleigh's clearances nearer home. (Lord Rayleigh's mother, the first Baroness Rayleigh, was a daughter of Ireland's premier aristocrat, the Duke of Leinster. Ascendancy families sometimes produced renegades who challenged the system: Lord Rayleigh's uncle, Lord Edward Fitzgerald, died resisting English dominance of Ireland during the 1798 rebellion.)

Moreover, benign sentiments towards the poor coexisted with severe legal sanctions against petty crimes that were almost certainly driven by poverty. In 1846, an eighteen year-old labourer received twenty-one days in solitary confinement for stealing a dung fork worth one shilling, "the property of Lord Rayleigh". Two years later, the Terling Place gamekeeper received a tip that five men and a youngster were planning a poaching expedition in Lord Rayleigh's woods. Run down through screeching of a hare, which they had caught in an illegal snare, the malefactors gave themselves up with sporting good humour, one of them remarking: "It is a pity you came to day for we should have made a good job of it." The magistrates took a more serious view of the episode, especially on learning that the poachers had damaged young trees in making their traps. Noting that the law provided for heavier penalties where more than five people engaged in such illegal acts, the bench imposed heavy fines. The accused could not pay and served three months in prison instead. In 1847, Terling's police constable apprehended a man from nearby Black Notley using an axe to lop a branch from an oak tree, "the property of Lord Rayleigh". The accused was lectured by Sir John Page Wood of Rivenhall Place, who has a small niche in History as the father of Katharine O'Shea, the celebrated mistress of the Irish leader Charles Stewart Parnell. Helpfully, Wood warned the accused that if he committed a second offence, he would be sentenced to twelve months in prison with hard labour, accompanied by a whipping. A clerical magistrate weighed in too: "a few years ago, young man, the offence was a capital one, and at that time you would have been liable to be hanged." Indeed, he added, as if suddenly overcome with nostalgia, he recalled "a case from this very neighbourhood in which a young man was executed for cutting a tree." Unfortunately, the court could only impose a small fine but, by adding the cost of damage, the delinquent axeman was ordered to pay eight shillings and twopence. He was released after "throwing the money upon the table with an air of great indifference, amounting almost to impertinence". Lord Rayleigh's authority did not extend to Black Notley. Of course, the fact that the law was harsh did not mean that the owners of the Big House were insincere in the generosity and compassion they showed their poorer neighbours. Lord and Lady Rayleigh were rightly praised for their courage in remaining at Terling Place when the parish was ravaged by cholera in 1867, organising charitable and medical support when one third of the 900 inhabitants fell sick in one of the worst outbreaks in Victorian Britain: 41 people died. Some of the responsibility could be attributed to the failures of the parish Vestry and the local Poor Law guardians, who doubled as a health authority. But, the words of the clerk to the Witham Health Board to a parliamentary enquiry, "you can hardly conceive a place more filthy", were also an indictment of the man who owned most of the parish. Rehousing had been imposed to create a peasant-free zone behind the mansion, but nothing had been done to clean up the village and wider parish. (Lord Rayleigh provided £1,700 in loan finance for improvements, and within three years Terling was described as a "model village".)

The ghostly trace of Mill Street

This view of the Tudor House (discussed in more detail below) from the churchyard shows the line of the former Mill Street, presumed closed c.1850. The gate in the red-brick wall now gives access to a private lawn. The photograph was taken on an autumn morning in 2021.

Church Road looking west to Terling Green

This photograph shows how the construction of Church Road opened the rear of the Tudor House to public view, although nowadays a high hedge provides privacy. Adjoining the village war memorial (formerly the location of the stocks) is a barn believed by the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments to date from the 15th century. (Historic England describes it as a granary.) The church spire may be seen in the background, to the left.

Church Road from the west

Church Road, looking east towards The Street

One major advantage of the new and wide road to the Green was that it would have enabled Lord Rayleigh's family to come to church by coach. One Tuesday in 1871, "[t]he village of Terling was awakened from its usual monotony" by the excitement of a fashionable wedding of the Honourable Clara Strutt, Lord Rayleigh's only daughter. The bride and her parents arrived at the church in "a regal carriage, with gaily caparisoned steeds", and "the village green was occupied by vehicles of every size and denomination, whose owners, standing on the seats thereof, made themselves secure of a good view of the bridal procession". None of this would have been possible before the reorganisation of c.1850: Clara would have been obliged to walk across the park to get to the altar.

The Green, looking west

This peaceful view looking west across Terling Green towards the river Ter shows the ground occupied by the White Hart until c. 1850.

The Green, looking east

This view of the Green, looking east is taken from the site of the former White Hart. The parish church can be glimpsed to the right. The Tudor House is screened by trees.

The Street, looking south

Prior to c.1850, The Street continued further to the south, beyond the present-day gates of Terling Place.

At about that time, Lord Rayleigh cleared several tenements, effectively moving the village away from the mansion and to the north. The occupant of the Tudor House, his steward Robert Ellis, gained some privacy that perhaps compensated him for the intrusion of the new Church Road at the rear of his home. At about the same period, to the north of the village New Road was built linking Hatfield Road to Owls Hill, presumably to create a bypass so that cattle and waggons being driven to Witham and Hatfield Peverel to Fairstead and Great Leighs would avoid Terling itself. Lord Rayleigh reduced the gap between Owls Hill and the historic village by building a school at the corner of New Road: twentieth-century residential development eventually created a continuous ribbon of housing linking the two.

Bell Corner becomes the village centre

One incidental by-product of Lord Rayleigh's remodelling of the village was that Terling acquired a new centre. The junction apparently referred to in seventeenth-century deeds as Bell Corner, formerly at the north end of the village, now became its focal point. Successive road closures across the Terling Place estate meant that Crow Pond Road (to the right in the picture), which led north-east to Fairstead, also became the route leading to Hatfield Road, and hence the link to Witham (to the east) and Hatfield Peverel (to the south). Below is the complementary view from Crow Pond Road as seen by the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments about 1920. The church spire may be glimpsed in the distance.

Terling village in 1597: a schematic plan

This schematic plan of the village, which is not drawn to scale, is based on the 1597 map of Terling by the Tudor cartographer John Walker.

Because the thumbnail sketches of buildings on the Walker map have suffered from the smudging and poking of the village area by greasy fingers, many locations in this reconstruction are approximate, and some names and identifications must be regarded as tentative and provisional. The distance from north to south of the village area was about 300 yards; the watermill on the river Ter was about 450 yards west of the church. The spine of the village was The Street, much longer in 1597 than today: as noted above, the construction of the Strutt mansion at Terling Place was accompanied by the clearance of its southern end. Mill Street led to the west, across the village green.

The Green was an established feature, specifically mentioned in the parish register in 1548, and probably the location of the annual fair. Although Walker's thumbnails are not easy to interpret at this point, it is likely that there were buildings on the west side of the Green, where the tithe apportionment map shows that the White Hart stood in 1844. Although I have not traced the White Hart before 1772, the sign was popular in the Middle Ages, and several nearby towns have examples housed in ancient buildings. In 1590, complaint was made that John Hobson, Terling's schoolmaster, "usethe comenly to spende great part of his tyme from his charge" playing "unlawfull games" such as dice at alehouses, "espetiallye at one Lillies of Tearlinge". Local schools usually operated in the parish church, so perhaps Hobson was tempted into the nearby White Hart. (John Lily died in 1591. Soon after, John Hobson married Mary Lily, widow. He was still Terling's schoolmaster when he made his will in 1604.) Access to tenements along the north side of the Green was via the Back Lane, which also led to water meadows beside the the river. It still exists as an alleyway, although truncated by a recent housing development.

Sir Thomas Mildmay's mansion

From the mid-thirteenth century (and certainly by 1259), the manor of Terling Place belonged to the bishops of Norwich. The pioneer Essex historian Philip Morant wrote that they had "a Palace in this place", punctiliously using the technical term for an episcopal residence. Unfortunately, others romantically assumed that such a building must have been grandiose and luxurious. The absence of any trace of marble halls and imposing colonnades was a problem: as the Chelmsford journalist D.W. Coller put it in 1861, there was "not even a cob-webbed corner of the old palace left". "Of the ancient palace of the Bishops of Norwich at Terling not a stone has been left standing," C.A. Barton more prosaically remarked in 1953. Perhaps the most ingenious interpretation has been offered by James Bettley, in his encyclopaedic revision of the Essex volume in Pevsner's Buildings of England series. Noting that the farmhouse at Ringers, a mile south-west of the village, had been rebuilt in the sixteenth century using timbers that were two hundred years older, he concluded that that their origin was "very probably the bishop's palace by the church that was demolished in the Early Tudor period." In fact, there is solid evidence that the mansion survived to pass into the hands of powerful private owners, first Henry VIII's lord chancellor Thomas Audley and later the Mildmay family of Chelmsford, and every reason to assume that Ringers was reconstructed from the materials of a former house on the same site.

Medieval bishops of Norwich owned five episcopal manors across East Anglia, which they used when on progress around their diocese. Most were also political figures, active in the royal court at Westminster – which required long and slow journeys to London. It made sense to maintain a sixth country residence at Terling, where they could break their journey to and from the capital. Mostly, they made brief stopovers: an itinerary of Bishop William Bateman's movements in 1354 showed him spending five days at Terling on his way to London in January, and a further three on a return journey in April. The break would have been welcome: we should not underestimate the toils and perils of medieval travel. In 1288, Bishop William Middleton died at Terling on his return journey from Gascony, where he had accompanied Edward I in his role as steward to the royal household. Yet even if the bishop's mansion primarily functioned as a kind of pied-à-Terling, important business was nonetheless transacted there. Following the Black Death, Bateman founded a Cambridge college, Trinity Hall. It was during a stopover at Terling in 1352 that he approved its statutes, providing the new academic community with its first constitution.

The 1597 map indicates that the mansion occupied by the bishops and their successors was located a little to the south-west of the parish church, its site now part of the grounds of Terling Place. Barton reported that fragments of "worked stone and rubble" had been found nearby, while Historic England regards the southern perimeter of the churchyard as a Tudor garden wall. The map's smudged thumbnail sketch seems to show a substantial gabled mansion, of two wings flanking a central hall – probably a larger version of the Tudor House, and maybe the product of the same fifteenth-century rebuilding programme. It was certainly well-equipped with chimneys, and may be confidently identified with the house occupied by Robert Mildmay that was charged for twenty fireplaces in the 1662 Hearth Tax.

The southern perimeter of the churchyard is believed by Historic England to be a Tudor garden wall, all that remains of the old mansion.

The mansion faced down a short access road, which joined the highway to Boreham that was closed in 1771. A rental of the manor of Terling Place, transcribed by Barton (who was not always totally accurate) and dated to about 1475, twice referred to an unidentified "Bourestreet". The term 'bower' seems to have described a high-status but unfortified residence, perhaps implying that it was not permanently occupied: a former royal palace and hunting lodge near Romford is remembered in the name of Havering-atte-Bower. This would have been an appropriate name for the bishop's house in Terling. The northern end of the access road was lined with tenements, possibly flanking an entrance courtyard. Further south along the same road stood another cluster of buildings. The apparent absence of chimneys on most of them in 1597 suggests that it was a farmyard. In the middle of what seems to have been an open space it is just possible to make out a tall, slender structure, built of brick and tile. This can only have been a bell tower, designed to summon labourers from the fields. Newton and Edwards also identified an exotic feature somewhere on the 1597 map, a banqueting house. If, as seems likely, this was associated with the mansion, it was perhaps an addition by Audley, who would have had political motives to feast his guests. This southern section of the village was cleared in 1772-3. (The fourth Baron Rayleigh, in his biography of his father, states that "[p]art of the original Tudor buildings, serving as kitchens and servants' quarters" survived until about 1820, when they were demolished to make speace for the wings that were added to the mansion.)

C.A. Barton noted in 1953 that "[n]o painting, engraving or description" of the mansion is known to exist. This is not wholly correct: in 1594, the geographer John Norden provided a laconic confirmation of the evidence of the Walker map: "Terlinge hall. A stately howse, Sr Tho. Myldemayes." (The name Terling Hall was later transferred to a manor house, Margeries, on the southern boundary of the parish.) Barton pointed out that the estate passed into absentee ownership in the eighteenth century, and he may have drawn upon local tradition to hint that the ancient buildings fell into disrepair. This, in turn, would explain why John Strutt, who purchased the estate in 1761, decided to erect a new house. A bundle of documents relating to various local properties, including a cottage adjoining the churchyard, formerly deposited in the Essex Record Office, was tagged with an eighteenth-century label: "The Old Hall adjoining to the churchyard in Terling". In 1768, on the eve of the construction of the new country house, the Essex historian Philip Morant stated of the manor of Terling: "The mansion house stands near the Church." Charles Strutt, in his 1939 privately printed history of the family, adds that the building had been reduced in size (a fate that also overtook Great Loyes and Terling Hall) and was then known as the Parsonage House. The estate having passed into the hands of absentee landowners, no doubt it made sense to use what remained of the Mildmay mansion to accommodate the vicar. John Strutt initially allocated £500 for its renovation, before deciding to decamp to an entirely new home a few hundred yards to the south.

It should be noted that it was highly unusual in Essex for a major private residence to be located so close to a village, and practically forming part of it. Most of the big houses of Tudor times were situated at a slight distance from the communities that their owners sought to dominate – such as Moulsham Hall at Chelmsford or Gidea Hall near Romford. The proximity of uncouth villagers would have been of little concern to the bishops of Norwich. Mostly, they stayed for short periods, and were accompanied by substantial entourages of servants who would have been capable of enforcing rough discipline upon any obstreperous yokel: more important for them would have been the convenience of the adjoining parish church. However, a different picture may be imagined once the mansion passed into the hands of private owners, since its size meant that they would likely to be families of some social standing. Generally, in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Essex, the gentry pulled the strings at local level, especially through serving as magistrates. The picture of a sizeable mansion standing in the middle of a village may conjure the words of a Victorian hymn: "The rich man in his castle / The poor man at his gate / He made them, high or lowly / And ordered their estate." The complication in this case is that the manor of Terling Place did not control all the tenements in the village: there are indications from wills that the Rochester family of Great Loyes owned some part of the village. Although the Strutt family energetically bought up land across the wider parish, as late as 1844, the tithe map shows that they did not own the houses along the north side of the village green. (This explains how the local Nonconformists managed in 1753 to acquire a site for a Congregational Chapel here, cheekily facing the Anglican church: it closed in 2017.) In his 1939 history of the family, the Honourable Charles Strutt described how his forebear, J.H. Strutt, "gradually [purchased] most of the cottages in the village" as a prelude to the c.1850 clearance of the southern end of The Street. Thus even in the early nineteenth century, the powerful squire of Terling Place did not own all the property on his doorstep.

A comparison may be useful here: in the entire century from 1550 to 1650, Ingatestone, a main-road village or small town, appears to have generated no presentations to the county courts regarding alehouses, either unlicensed or unruly. There is no reason to think that Ingatestone people were exceptionally well-behaved. It is much more likely that the powerful Petre family of Ingatestone Hall were able to use their ownership of the whole community to enforce orderly behaviour without invoking the sanction of the law. Indeed, their founder, Sir William Petre, forbade his tenants to take any case to court without first consulting him, and threatened to fine them heavily if they disobeyed. In the mid-eighteenth century, large-scale property purchases enabled the Strutt family to impose a code of conduct upon Terling's sole remaining hostelry. An admirer lamented the contrast with his own community "where every man is unfortunately his own master, and no one can be found to regulate the actions of the ignorant and unthinking". A century earlier, divided control in Terling may have made it necessary to appeal to the magistrates to suppress irregularities.

The Tudor House

The Tudor House (then known as the Manor House) photographed for the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments, c. 1920. Note the gates and fence across the former Mill Street.

The Royal Commission on Historical Monuments states that the Tudor House was erected in the fifteenth century. (Pevsner and Bettley accept this date, although Historic England suggests a sixteenth-century origin.) It is possible – although it can only be a guess – that it was erected by James Goldwell, bishop of Norwich from 1472 to 1499. He served for a time as principal secretary of state to Edward IV, and was an active member of the king's council who later supported Richard III's grisly grab for the throne after Edward's death in 1483. (He is believed to be the first Englishman to have owned a printed book, purchased in Hamburg in 1465 while on a diplomatic mission to Germany.) Goldwell was a great builder, not only overseeing the renovation of Norwich cathedral after a major fire, but reconstructing Thornage Hall, an episcopal manor near Holt in north Norfolk. (He died at yet another country property belonging to his see, Hoxne in Suffolk.) Like most clerical careerists of that era, Goldwell was a serial pluralist who, for five years early in his career, had been rector of Rivenhall, a parish close to Terling.

It is puzzling that so substantial a building, in the centre of the village, seems to have left very little trace in the records. It probably doubled as a steward's house and estate office, its central hall a semi-public zone where tenants raised their concerns and paid their rents. Equally curious is the mystery that it seems to have had no name. In 1848, White's Directory identified it as the house occupied by "R. Ellis, Esq." (Lord Rayleigh's estate manager), adding that it was "in the Elizabethan style, and contains some finely carved oak wainscoting". In the 1861 and 1871 census returns, Ellis and his family were simply recorded as living opposite the churchyard. In 1881, the building, then in multi-occupancy by Terling Place employees, was listed under the mundane address of "Pay Office, Church Green". Soon after, it became the home of George Gordon, the resourceful laboratory assistant who made possible many of the third Baron Rayleigh's scientific experiments. Lord Rayleigh's biographer, his son, states that "Gordon was assigned an old Tudor house just outside the grounds", and a footnote reference to the photograph in the report of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (above) confirms the identification. The 1891 census recorded Gordon as living with his father and sister at "Pay Office, Terling Green". So far as I can trace, the building first appears as the Manor House in the 1914 edition of Kelly's Directory, when it was occupied by an "assistant estate agent", a member of Lord Rayleigh's administrative staff. Its renaming as the Tudor House seems to be connected with Mary Rolt, widow of an Anglican clergyman, who moved in sometime after her husband's death in 1926. Local historian C.A. Barton evidently disapproved of the innovation, and called it the Manor House in his 1953 book on Terling. In fact both names were misleading: no lord of the manor ever lived there, and it was almost certainly constructed before Henry VII came to the throne.

However, the Tudor House was extensively remodelled in the sixteenth century. The central hall, originally open to the rafters and warmed by a kind of indoor camp-fire, would have been a miniature version of the dining halls still to be seen in the older Cambridge colleges. "Probably late in the 16th century", concluded the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments, the hall was divided into two storeys, with more convenient access to the upper floor provided by a staircase tower added in the seventeenth century. Three brick chimneys were incorporated, two of them visible in the thumbnail sketch on the 1597 map, with a third, smaller chimney added later. A handsome bay window was built into the ground-floor apartment of the west wing, sitting on a solid brick plinth, and with the glass panels fitted into wrought iron frames that were probably hammered by some Terling blacksmith (https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1147379).

The Tudor House, on a misty morning in September 2021. The brick plinth supporting the Elizabethan bay window can be seen closest to the camera.

Brick, tile and Terling

The chimneys on the Tudor House may not have been new in 1597. Writing twenty years earlier and fifteen miles away at Radwinter, William Harrison famously commented on "the multitude of chimneys lately erected" in counties like Essex. What is striking about the Walker map is that it shows that every home in the village had at least one chimney. Moreover, each of the fifty or so village buildings – barns and outhouses included – had a tiled roof. This was obviously a fire precaution, made necessary by the transition from the use of wood as a fuel to coal: if sparks ignited thatch, a blaze might rapidly spread to neighbouring tenements. (An 'Elizabethan' chimney dated to 1613 on a house facing Terling Green, discussed below, was probably an upgrade: style is not always a reliable guide to dating.) However, when Newton and Edwards scrutinised the 1597 map in detail, they found that 26 of the 40 dwellings in the wider parish were thatched, most of them with a smoke-hood, a primitive beehive-like gadget that filtered wood smoke out of a house but was of little use in removing the noxious fumes from the increasingly popular rival fuel, coal. (The 1597 map covered about one-third of the parish.) Wrightson and Levine concluded that, by the sixteenth century, manorial courts exercised little practical jurisdiction or regulatory control in Terling. However, the standardised use of chimneys and tiles throughout the village can hardly be the result of multiple individual initiatives: landlord control must be suspected.

Brick had been used as far back as the mid-fifteenth century in the construction of Faulkbourne Hall, although at that stage it was usual to import skilled workers from the Low Countries. Terling's first recorded bricklayer seems to have been Robert Grene in 1574. A major construction project, using brick, had recently commenced three miles south-west of the village, at New Hall, Boreham – the rebuilding of Henry VIII's former palace, a major enterprise – and Grene may have been employed there. The term 'bricklayer' usually implied a jobbing builder, sometimes even a large-scale entrepreneur: Grene, also described as a yeoman, was probably a farmer and a person of some standing locally, although he appeared in the Essex court records after allegedly drawing a dagger during a fight in Terling churchyard. Making arrangements for the disposal of his estate in 1583, John Rochester of Great Loyes listed a clamp of bricks among his assets, a most unusual feature in Essex wills. Thomas Wistocke, tiler, who made his will in 1592, may have been the craftsman who created the roofscapes that still define the older houses of the village. Given the impressionistic nature of contemporary spelling, Richard Wyscoke, accused of assault in 1609, could have been a relative. An allegation that Wyscoke had seized his victim's purse was dropped, but it is tempting to suspect a dispute over building work. Although Terling's transition to brick seems to have been an Elizabethan phenomenon, the parish had two more bricklayers in the first decade of the seventeenth century. Francis Swinburne and Richard Hilles seem to have been men of substance, since both only feature in official records because they stood surety for neighbours.

The local landscape may contain another feature linked to Terling's adoption of brick. Hidden in woodland across the river from Terling Place is a stretch of water covering about an acre and known as the Swan Pond. It can hardly be a mill dam: no such installation is recorded in seventeenth-century documents, nor are there any feeder streams, which would have been needed to power a waterwheel. (The Honourable Charles Strutt does refer to a "little water-mill at the Swan pond", demolished in the early nineteenth century, but this may have been a later addition: it is hard to understand who anybody would excavate a pond at this location for a "little water-mill.") Both for security and convenience, a fishpond would have been located closer to a house, and it too would probably have required running water. The Swan Pond appears on the 1597 map (although it is not named), which rules out any subsequent creation by landscape gardeners, even though it was later incorporated into the Terling Place ornamental park. The irregular shape of the Swan Pond suggests that it originated as an excavation, very likely to quarry brickearth. I have found no record of any brickmaker among the residents of the parish, although a Terling man, "Shepheard the Brickstriker", was working in Braintree in 1623. However, there were brickmakers in the local area, and it was common practice to manufacture bricks close to the place where they were needed. The Swan Pond and the attractive red roofs of the village may be linked as part of the legacy of Terling's conversion to the new, safer building material.

Alehouses and inns

Much of the social control activity of the local courts was directed at that perennial sink of iniquity, the alehouse. Wrightson and Levine calculated that one third of all prosecutions between 1560 and 1649 related either to disorderly behaviour in alehouses, or to their operation without a licence – there being a peak of fifteen of the latter cases in the decade after 1609. Two questions arise in relation to alehouses and the attempted reconstruction of Terling in 1597. First, can we be sure that all such hostelries operated within the village area, or were they perhaps scattered more widely around the five square miles of the parish? It has been estimated that in the sixteen-thirties, Essex had one alehouse for every 125 people. There are some indications that magistrates and parish officials were aware of this approximate ratio: in 1616, it was noted that there were "too many alehouses in Witham by six", and, two years later, complaint was made that the number of alehouses in Hatfield Peverel was "more than needes". Given that the village of Terling contained perhaps 250 people, this might suggest that it could support only two alehouses. However, it is also likely that village hostelries tended to serve a wider area, as might be deduced from the apparent absence of outlets in nearby Fairstead. There was an intriguing episode in 1627, when the justices agreed to suppress an alehouse in Beauchamp Roding, a 1200-acre entirely rural parish within twenty miles of Terling. Locals complained that the offending alehouse was located in an inconvenient place alongside a wood, and that, in any case, they had no need of such a facility. Residents of the parish, which contained 220 people in 1801, were presumably expected to build up a thirst by tramping to the fleshpots of Fyfield, which did have alehouses, although in 1627 some of those also faced censure. It seems reasonable to conclude that most of Terling's alehouses were in the village: in urban Witham around 1620, there may have been as many as one outlet, legal or otherwise, for every forty people – or, more realistically, every twenty adults. However, with nineteen allegedly illegal operators prosecuted in Terling over nine decades, there was surely room for some in the wider parish. As discussed later, it seems reasonably certain that John Norrell, who sold ale for over forty years, entertained his customers in his cottage (still called Norrells) over half a mile west of the village.

The second question that arises relates to the definition of an alehouse. At the lower end of the spectrum, it must have been difficult to define an illegally operating alcohol business. It was surely understandable that country people would gather for warmth and conviviality in the home of some friendly neighbour, and it might be simple good manners to contribute a few pennies to share a kilderkin of ale and the cost of a candle. The boundary between hospitality and commerce must have been a very fine line. In 1620, Essex Magistrates were told that there were forty unlicensed alehouses in Chelmsford and Moulsham – evidence which came from a brewer, who was well-placed to know. Wrightson and Levine found that those prosecuted or operating unlicensed alehouses were mainly poor, and from the lowest ranks of society. Generally, their activities only came to the notice of the courts when there were the complications of incriminating behaviour – drunkenness, gaming, swearing, dancing and Sabbath breaking.

Yet it is reasonable to assume that, hidden within the often-repeated complaints about "alehouses", there were some enterprises that amounted to continuing businesses, operating on a larger scale, providing food and accommodation – in short, the occasional village inn. In the sixteenth- and seventeenth-centuries, merchants and publicans used signs to identify their premises. In the use of such signs, there would obviously be a difference between the recognised hostelry, which wished to attract customers, and the illicit shebeen that sought to avoid unwelcome attention. Unfortunately, the local courts dealt almost exclusively in personal names, licensing individuals and prosecuting illegal traders by name alone, rarely if ever specifying a business identity.

The reconstruction of Terling in 1597 takes account of the possibility that two such enterprises were operating in the village. Of the Bell (marked F on the schematic map), it can only be said that if it was selling ale, it was keeping a low profile. It was mentioned in the local rental of c. 1475, and in a will of 1524, but I have not identified it thereafter. The Essex Record Office holds deeds dating from 1641 to 1665, of property "in the Back Lane near Bell Corner". The name may simply have been carried forward from earlier legal transactions, preserving a formal memory of a hostelry that was no longer trading. However, the deeds do indicate that the Bell had been or perhaps was still located close to the corner of the highway to Fairstead, now Crow Pond Road. Indeed, it is tempting to pinpoint the building now occupied by the village stores, which Historic England regards as late fourteenth-century in origin but altered in Tudor times. In fact, it seems reasonable to assume that some alehouses functioned quietly over long periods, causing no trouble and hence leaving little trace in county records. William Holmes was licensed as a victualler in 1607, but nothing more is heard of him until the Puritan vicar Thomas Weld flexed his muscles and tried, unsuccessfully, to have him closed down twenty years later. Perhaps the Bell, tucked away at the north end of the village, also operated unobtrusively under the judicial radar, maybe even with Holmes as its landlord.

There is much firmer evidence that the Angel (marked E on the schematic map) operated prominently and sometimes controversially right in the middle of Terling village, and that its successive proprietors were engaged in much more than pulling pints for peasants. Wrightson and Levine supply the outline of the seventeenth-century story, but do not specify either the nature or the location of the enterprise. In 1603, Thomas Holman married the widow of John Aldridge, who had died the previous year, and had presumably been the landlord of the Angel. An outsider, Holman was unpopular in Terling, not least because he operated on a grander – and notably more alcoholic – scale. Sometime in the middle of the sixteen-twenties, he was succeeded by another John Aldridge, probably his stepson. His will, made in 1665, described him as an innholder, and named the premises as the Angel, making the connection that court records never troubled to note. Fortunately, the Angel can be traced through other sources. In 1684 the parish register noted the baptism of Charity Chandler, daughter of a wayfaring couple who, at a crucial moment in their lives, had found room in Terling's inn. In addition to accommodation, the Angel also served meals: in 1745, members of the local Vestry rewarded themselves for their labours by spending four shillings on breakfast there. It could also provide comfortable meeting space for the gentry. In 1788, John Strutt of Terling Place wanted to divert part of the public highway that he had built seventeen years earlier to take traffic further from his mansion. The Essex magistrates, or enough of them to do the business, obligingly held a special meeting at the Angel, which happened to be at the corner of the stretch of road he wished to obliterate. The alteration was agreed.

Those magistrates pinpointed the starting point of the road closure, as "the Three Want Way in Terling Street by the Angel near the church". (A three-want way was an Essex term for a T-junction.) The location is confirmed by other deeds dating from 1665 which identify Mill Street as leading from the Angel to Church Green adjoining churchyard, and the road from the Angel to Terling Mill. It is indicated on the 1597 map as a tenement set back from the adjoining cottages: eighteenth-century deeds confirm that it stood on half an acre of ground. The Angel was situated half way along The Street, on the east side, facing down Mill Street – at the central point of seventeenth-century Terling. Although I can only trace the name to 1666, the Aldridge-Holman business was operating as far back as 1602. The sign was probably of pre-Reformation origin: rampaging Puritans smashed images of angels, and it would hardly have been a smart business move to adopt such a logo in the seventeenth century. The point deserves to be underlined: the Aldridge-Holman hospitality business operated on a larger scale than the average alehouse, and it was located right in the middle of the village as it was structured in the seventeenth century. If its patrons reeled home drunk, their raucous revelry would disturb the residents of the Tudor House and possibly also annoy the occupants of the mansion itself. When Terling's representatives complained about Thomas Holman and John Aldridge, they were not simply grumbling about a perennially wayward alehouse, they were demanding regulation of the village's most prominent inn.

There were phases when Terling's spokesmen most certainly did complain. The account given by Wrightson and Levine of the conflict around Thomas Holman in the early years of the seventeenth century can be expanded, and surely acquires new significance when placed in the context of the Angel and its position in the village. PPEV states that Holman was a newcomer to Terling when he married the widow of innkeeper John Aldridge in 1603. (The following year, obviously isolated within the parish, he called upon two sureties from farmers at Castle Hedingham, a village about fifteen miles to the north, which suggests he came from there. Both communities had market links to Braintree.) It is clear that Holman was unpopular, and one local farmer, Richard Rochester, was determined to drive him out of business. A member of one of the dominant Terling families and cousin of the current owner of Great Loyes, Richard Rochester was variously described as a yeoman and a gentleman. He believed in enforcing his demands, and had previously twice appeared before the courts, once for evicting a neighbour and once for seizing sheep in lieu of alleged unpaid rents. He farmed at "Owles", which was described as located on the east side of the road from Great Leighs to Maldon, probably close to the site of the future Rayleigh Arms at Owls Hill, close to the village. In January 1604, making a rare court appearance as a prosecutor, Rochester won the first round against the landlord of the Angel, who was forced to promise to desist from selling wine and beer. However, there was a loophole that Holman evidently exploited: he was given "tolerance" to stay in business until "Hallowtide" in order to sell his stock of wine. Hallowtide is a three-day period in the Church calendar that begins with Halloween on 31 October: Holman had managed to secure almost a year's stay of execution. This gave him the space either to ignore the order to close in November 1604, or successfully to lobby the justices to allow him to remain in business – the county records are defective.

The reference to Holman's stock of wine confirms that he was running something more than a village alehouse. The fact that he was described on several occasions as a vintner may also indicate that he planned to operate on a scale previously unknown in Terling. Vintners were a long-established feature in the towns of Essex, and those based in Maldon supplied a wide area of the surrounding countryside, although probably mostly to prosperous and genteel customers. Major inns along the main highways served wine to upmarket travellers. We should also remember that, if the fermented juice of the grape was associated with self-indulgent decadence, it also formed part of one of the central mysteries of the Christian faith, the act of Holy Communion. The Reformation had widened the market here, by allowing laity to participate in the sacramental wine. Thus there was nothing new about a wine culture in Essex, but, with Holman, it may have arrived in Terling in a new and wider form.

Bizarre though it may seem, the international situation perhaps influenced the politics of this Essex parish. When James I became king in 1603, he began to wind down England's war with Spain, a conflict that had begun in 1585. Although a formal peace treaty was only concluded in August 1604, it is possible that wine was already becoming cheaper. Spain's vineyards were famous for exporting sack, a fortified wine that was the forerunner of sherry. It was the favourite tipple of Shakespeare's comic character, Falstaff: since he was unveiled to playgoers in 1597, sack must have been reaching the English market through neutral carriers even during the war years. Half a century later, a Chelmsford innkeeper was prosecuted for selling sack at a shilling a pint, the regulated price being ninepence. Even at the official price, a pint of sack would cost a labourer a day's wages: no wonder Terling officials would complain, sometime in the sixteen-twenties, that the next landlord of the Angel, John Aldridge, was "harbouring" drinkers who were "soe poore that many of them have almes of the parishe and their wifs and children beg in the parishe". And if sack was sold by the pint to unsuspecting country folk who quaffed it like low-alcohol ale, it is hardly surprising that there were occasional cases of total inebriation.

Holman had weathered the attempt to close the Angel in 1604, but Richard Rochester renewed the attack three years later. Augustine Norrell, who supported him, was hardly a disinterested stakeholder: his father was a veteran alehouse keeper. The two may have acted out in support of John Aldridge the younger, who had been about seventeen when his father died in 1602. (He took over the Angel about 1625, and ran it for forty years: at his death in 1665, the parish register noted that he was eighty years of age. Terling people perhaps felt sympathy for a young man elbowed aside from his inheritance by an unpopular step-father: in 1607-8 John Aldridge would have turned twenty-one.) Although details of the case do not seem to have been recorded, the complainants argued that Holman was a drunkard who was not fit to run an inn – this was an attack on the innkeeper, not an attempt to shut down the business as such. Whether he was once again threatened with closure or subjected to restrictions, the landlord of the Angel reacted so furiously that, in January 1608, his assailants compiled a detailed indictment of his misconduct. Naturally, they laid most stress upon the fact that Holman had wildly denounced the justices in diatribes that could not be decently repeated. He had also accused Rochester and Norrell of perjury, and marked the season of goodwill by abusing the parish constables in church on Christmas morning. Much of this was undoubtedly unpleasant, but it did not necessarily constitute a crime. Holman had spoken of his wish to kill Rochester, but with the saving clause that murder was illegal. When urged to calm down, he replied with a "very contempious" but entertainingly scatological gesture that involved him standing on one leg: once again, whatever he had broken, it was not the law. He had allowed a customer to become so disgustingly drunk (again, the details could not be repeated) that Henry Rayner, the local wheelwright, had felt obliged to take charge of the victim overnight. However, nobody seemed to know the man's name, although he had shared his drinking marathon with Terling's premier lout, John Clark, who had attempted to rape a woman at St Osyth three years earlier. More serious were allegations of violence. Holman had been restrained when he had produced a short stabbing sword to settle a dispute in his hostelry. He had also (allegedly) retaliated against those who sought to destroy his livelihood by attacking theirs. An attempt to saw through the palings of a fence at Rochester's farm had been frustrated (presumably Holman hoped the livestock would stray), but he was fined for breaking into Owles and assaulting his principal foe. His critics also found their ploughing equipment damaged.

Until the autumn of 1610, residents lined up on either side of the feud, standing surety for the principals and no doubt contributing to division in the community. However, the record then falls silent. It seems it was tacitly accepted that Holman would continue to run the Angel. Complaints were intermittent, and almost pro forma. In 1618, early in the climactic crackdown that is emphasised in PPEV, Holman was one of three so-called alehouse proprietors denounced to the magistrates for allowing disorder on their premises, serving drink to customers who should have been attending church, and allowing them to play at cards and dice. From the mid-sixteen twenties, parish officials intermittently pursued what Wrightson and Levine called "the harassment of a repetitive offender", his successor, John Aldridge. Thus in 1625, and named as "John Atteredge of Terling vintner" (possibly a transcription error), he was prosecuted "for suffering Robert Tunbredge, a stranger... to sit drinking and tippling in his house" in a drinking session with three Terling men. In 1630, Aldridge was reported for allowing customers to play shovelboard. To understand the charges, it is necessary to appreciate that Aldridge was more than the "disorderly alehousekeeper" of PPEV. From the mid-sixteen twenties, Essex magistrates seem to have contained the problem of small-scale illegal alehouses by targeting the sources of supply: heavy fines were imposed upon brewers who sold ale to customers in quantities beyond their likely domestic and family consumption. By contrast, the allegations against Holman and Aldridge formed part of an ongoing regulatory process, a form of armed neutrality, since nobody seriously expected that so substantial a business as the Angel could be closed.

This extended discussion of my attempted reconstruction of the village of Terling in 1597 highlights two key points for a re-evaluation of the work of Wrightson and Levine. The first is the potential importance of the mansion house, listed by John Norden in 1594 as one of the 92 most important in the county, but not mentioned in PPEV at all. Since the house was unusual among large gentry residences in Essex in being located within the village area, it seems reasonable to re-examine the 'Terling thesis' to ask whether it has placed enough emphasis upon the controlling role of a major landowning family, even though this may be difficult to trace through records which name humbler parish representatives as the source of information supplied to the courts. Second, it is useful to grasp the lay-out of the village to appreciate the importance of the Angel, apparently Terling's principal inn, a hostelry that evidently operated on a grander scale than the mere alehouses with which it was classified for the purposes of law enforcement. Its location at the then-central point in the village meant that the Angel had the maximum capacity to cause annoyance to the residents, especially to the residents of its near-neighbour property, the Tudor House, and probably to the high-status occupants of the mansion house itself. A reconsideration of the evidence presented by Wrightson and Levine may perhaps conclude that the most remarkable aspect of complaints about the Angel is not that local reformers sought to close the Holman / Aldridge enterprise, but rather that they tacitly accepted it as a permanent and integral feature of the community, albeit one that required constant regulation.

The role of the gentry