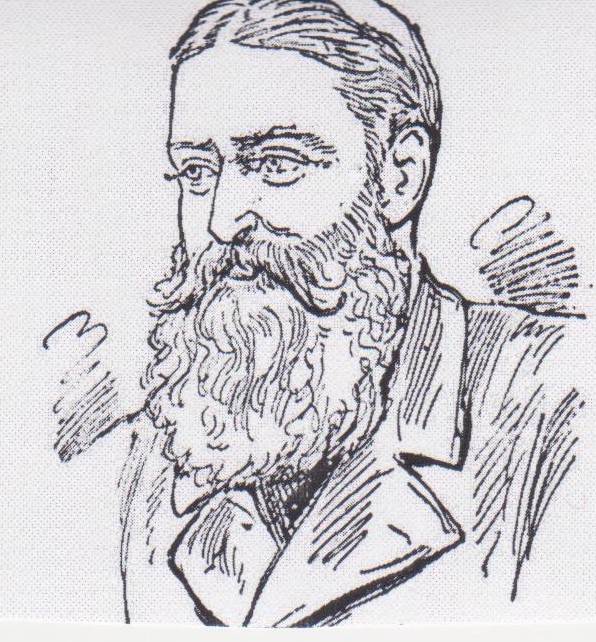

From Butt to Balfour: Edward King-Harman (1838-1888)

Edward King-Harman was a Protestant and Conservative Home Ruler in the eighteen-seventies who became a Unionist and a defender of his fellow landlords in the following decade. Some aspects of his journey from Butt to Balfour provide illuminating contrasts to the career of his contemporary, fellow Protestant landlord Charles Stewart Parnell.

A founder member of the Home Rule movement in 1870 and an early and vigorous champion of the cause, King-Harman was returned unopposed to Parliament for County Sligo at a by-election in 1877. Although he had been generally regarded as a supportive and paternalist landlord, he lost his seat at the general election three years later. By the time he returned to Parliament in 1883, at another by-election, this time for County Dublin, the Land War had left him financially embarrassed and personally embittered, deeply pessimistic for the future of his class. In 1885, he switched to an English constituency, the Isle of Thanet division of Kent, and spoke in opposition to Gladstone's Home Rule Bill the following year. In 1887, in a highly controversial move, Lord Salisbury's Unionist government appointed him parliamentary under-secretary for Irish affairs, making him a somewhat mechanical spokesman for the chief secretary in the House of Commons. His journey from Butt to Balfour in less than decade ensured that his front-bench experience was distinctly unhappy, and sympathetic commentators alleged that the frequent parliamentary maulings he endured from Irish MPs contributed to his death in June 1888. In another eerie parallel, both died young: Parnell at 45, King-Harman at fifty. King-Harman does not appear in either the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography or the Dictionary of Irish Biography, presumably being not important enough for the first and not Irish enough for the second. This essay is intended as a partial contribution to filling that biographical gap, but it is offered with the hope that more substantial studies of his career may follow. [2022: my comment was unkind. I understand that King-Harman is now under consideration for inclusion in the DIB.]

The King family of Rockingham King-Harman's first male ancestor came to Ireland in 1601, and soon after acquired the core of the Rockingham estate in County Roscommon. The eighteenth-century mansion itself stood close to the shores of Lough Key, a few miles from Boyle.[1] The subsequent story of the dynasty is complicated by its divisions into various branches, sometimes reunited by marriage. Titles of nobility conferred by the cardboard coronets of the Irish peerage also make it difficult to trace individuals, while their surnames mutated generation by generation as impecunious male Kings levered their way from one landed heiress to another. Ruthless simplification of dynastic intrigue and a focus upon King-Harman's immediate forebears is required to explain how he came to be one of Ireland's leading landowners. A fortunate marriage enabled his grandfather, Viscount Lorton, to add the Harman lands at Newcastle, near Ballymahon in County Longford. Hence his second son became Laurence Harman King-Harman, although – unhelpfully it might seem – he was known in the family as Harman King-Harman. Since he became the father of the subject of this essay, he is referred to here as King-Harman senior. Younger sons of landed families were frequently left with only small annuities to support them, but King-Harman senior was fortunate in inheriting the well-run Newcastle estate in 1838. King-Harman himself was born that year, and may be assumed to have spent much of his childhood at his father's County Longford home.

Thus far there seemed to be prizes for everybody in the King dynastic raffle. Unfortunately, Robert King, Lord Lorton's heir and King-Harman senior's elder brother, created embarrassing problems for his kinsfolk. Although his enthusiasm for politics and alcohol caused him to run up massive debts, he had at least secured the succession by fathering a son through his marriage in 1829 to Anne Gore-Booth, of the well–known family of Lissadel in County Sligo. Unfortunately, there were marital problems, and Anne King began a relationship with a French aristocrat. When she produced a further son in 1848, Robert King disavowed parentage. The evidence was not sufficiently conclusive to secure him the divorce that he sought two years later, a failure that drove him to embark upon determined legal moves to ensure that "the Frenchman", as he referred to the disputed child, was written out of the succession to Rockingham. When Robert King's acknowledged firstborn died in 1871, leaving only a daughter, Rockingham – which always passed through the male line – was inherited by King-Harman senior.[2] He owned Rockingham for just four years, and preferred to continue residing on the Longford property that he had inherited over thirty years earlier. Rockingham was enmeshed in a legacy of bad management that hardly made ownership a pleasure. Upon the death of King-Harman senior in 1875, his son, the popular Home Ruler, became not only one of Ireland's biggest landlords, but also one of Ireland's unluckiest.

King-Harman: the early years Edward Robert King-Harman was born on 3 April 1838, the eldest of five surviving sons.[3] His parents were "exceptionally religious".[4] His mother, Mary Cecilia Johnstone, was a Scot, whose grandfather had established a very large family fortune from the loot of eighteenth-century Bengal: as a young Army officer, King-Harman would help reconquer northern India after the Mutiny-Rebellion of 1857-8. Biographers now generally accept that Parnell's American mother had little influence on his childhood, since she left the family home at Avondale when her marriage collapsed when he was a small boy. But whereas awareness of his American descent probably reinforced Parnell's sense of an Irishness that rejected English overlordship, King-Harman's upbringing more likely took place within a sense of a wider British identity, which his phase of enthusiasm for Home Rule would modify rather than replace. Unfortunately, Cecilia, as she was known, seems to have bestowed little warmth upon her children. "She became a formidable matriarch and was much feared by her sons."[5]

Following in the footsteps of many of his male forebears, King-Harman was sent to Eton. (Parnell, whose father was an Etonian, was presumably spared because of his fragile health in childhood.) King-Harman was proud of the school, in 1883 pompously defending Eton boys against an accusation of cruelty to animals. [6] A rare sympathetic obituary claimed that he had to contend against anti-Irish prejudice, "and many a young Etonian received ugly punishment from the young Irish athlete from Roscommon as the reward for his contempt".[7] Since by manhood he had grown to a height of over six feet (180 cms) and weighed more than eighteen stone (115 kilos),[8] it is tempting to imagine him as a polished product of Eton, one of the senior Ascendancy boys who claimed the privilege of presenting the Headmaster with a bowl of shamrock on St Patrick's Day. The truth is markedly different. He was admitted to Eton in 1847, at the age of nine. Reforms in the public school system from the eighteen-sixties gradually raised the general age of admission: Eton, which took boys as young as eight, did not adopt new regulations until 1872 fixing the age of admission from eleven to fourteen. A quarter of a century earlier, Eton was teaching very small boys at primary level. King-Harman was allocated to the Third Form, which was divided into sets called Sense and Nonsense. In both, the curriculum was entirely limited to the writing of Latin verses. One group translated these from English, but the other was freed from all challenge of meaning and made to concentrate solely upon the elegance of scansion. King-Harman was allocated to Sense, which suggests that he may have received some prior home tutoring. He seems to have progressed steadily through the school, but left early in 1853, around the time of his fifteenth birthday.[9] In material terms, his childhood had been privileged; emotionally, an intimidating mother and a Spartan public school may have made it less enriching. Although his puritanical parents may have shielded their offspring from the scandalous story of aunt-by-marriage Anne Gore-Booth, the failed divorce episode probably left its mark on the twelve year-old King-Harman, and may explain some of the patriotic fisticuffs that he later attributed to his schoolboy days.

King-Harman left Eton to prepare for a career in the Army. He was commissioned as an ensign, the lowest officer rank, in May 1855, and promoted to lieutenant – a promotion which his family purchased – one year later.[10] His regiment, the 60th Rifles, was posted to India to take part in the suppression of the 1857-8 Mutiny/Rebellion. According to family tradition, he took part in the siege of Delhi, in which the 60th Rifles were prominently engaged throughout the summer of 1857. However, a note in a later Army List specifies service the following year in the reconquest of Rohilkhand, a district across the Ganges to the north of Delhi. In the immediate crisis of the uprising, the British Raj had opted to bypass the area in order to crush the main centres of insurgency. But this did not mean that Rohilkhand was a sideshow, nor was the military intervention there merely a mopping-up operation. King-Harman took part in the recapture of two major towns, Bareilly and Shahjahanpur, for which he received the standard campaign medal. He once remarked that he had "led Irish soldiers under very severe fire", but supplied no details. His only recorded personal contribution to the campaign was described in a barbed note accompanying his Vanity Fair portrait of 1886 which stated that: "While in India he distinguished himself by the peculiarly Irish exploit of parading a religious relic captured as prize of war throughout a population most likely to resent the parade."[11]

Active service under quasi-guerrilla warfare conditions seems to have strengthened King-Harman's external defences of insensitivity, but it did not make him into a team-player. As soon as the regiment returned to England, in 1859, he sold up his commission. "He left the army, not because he did not love soldiering, but because he hated – to use his own words – the 'infernal cads' they made officers."[12] A war scare with France in 1859-60 sparked interest in amateur soldiering, and he threw himself into the militia, which was organised on a county basis and hence more likely to recognise the leadership claims of prominent landlord families. In January 1860, he was promoted to the rank of captain in the Royal Longford militia regiment. A subsequent promotion in 1878 leaped several ranks to make him an honorary colonel.[13] This over-inflation of military status would symbolically reflect his artificial elevation in politics. During his Home Rule days, he was popularly known as "The Captain". As a Unionist and defender of landlordism, he became the more intimidating Colonel King-Harman.

As a young man he seems to have engaged in the jolly japes of a privileged drone, "something of a roysterer [sic] … in a harmless sort of fashion", who took pleasure in minor acts of vandalism such as twisting knockers from front doors.[14] He patronised prize-fighters, and was handy with his own fists. One day, in the West End of London, he heard a dandified Englishman reject the pleas of an Irish beggar woman, telling the "dirty Irish something or other" to go to Hell. King-Harman intervened and flattened the abuser of his country, "to the utter ruin of his sartorial finery." He was arrested but the matter was dropped when he pointed out at the police station that he was related to an earl.[15]

An escapade late in May 1861 ended less amiably. King-Harman and eight or nine other noisy young rowdies ended the festivities of Derby Day at Cremorne Gardens, a fashionable resort in Chelsea. Well after midnight, and evidently well lubricated with alcohol, they determined upon a "lark", linking arms to form a cordon and drive other patrons out of the bar. Staff locked the nearby coffee room, but King-Harman and two of his friends kicked down the door and forced an entry. The hearties chased customers from the tables, threatening to trash the establishment if they were resisted. Two police constables briefly managed the remarkable feat of taking the massive King-Harman into custody, but his associates shouted "Rescue!" and dragged him free.

The Westminster magistrate, Thomas Arnold, took a dim view of the episode. King-Harman initially secured the services of William Ballantine, one of England's most senior lawyers, who rarely appeared in a police court. However, Ballantine's offer to post bail of £25,000 was refused, and King-Harman spent four days on remand in the local House of Correction, Coldbath Fields, a prison with a grim reputation. The initial charge of assaulting a Cremorne employee carried only a fine of £5, but Arnold insisted on summoning King-Harman back into court to answer for the further, and much more serious, offence of assaulting the police. The junior counsel who now represented him offered no evidence for the defence but tried the usual ploy of fake contrition ("no one more seriously regretted what had happened than his client"). He also ingeniously argued that since King-Harman had technically been in police custody at the time of the rescue, he could not be guilty of assaulting them. The magistrate brusquely rejected the excuse, and pronounced that "the gang" had gone to Cremorne "with the express object of disturbing the public peace" and determined to resist any attempt to prevent them. "A pecuniary fine upon the defendant would not in any way meet the case. … He was in the habit of dealing with cases of the same kind daily." The usual sentence was evidently two weeks in Coldbath Fields. Since King-Harman had already spent four days there on remand, Arnold sentenced him to ten days' corrective detention.

The accused and his friends manifested "the greatest consternation" at the outcome, and intimated that they would immediately apply to the authorities for clemency. Two days later, it was announced that the sentence had been "set aside", and the prisoner released.[16] The Home Secretary, Sir George Cornewall Lewis, was a solemn and intellectual politician, but, when challenged to explain his decision in the House of Commons, he criticised the "unnecessary length" of King-Harman's sentence, and adopted a strangely benign interpretation of the evidence. "There was no question of any violence used or blows struck. … It appeared to me that after he had undergone two days' imprisonment, the justice of the case was sufficiently met, and I directed him to be liberated."[17] The explanation was received with widespread contempt. "Mr King Harman is a man of good birth and large property; consequently, an impunity is accorded to him, for which a plebeian pauper or a humble mechanic would seek in vain." King-Harman "deserved an infinitely heavier punishment than a low-born perpetrator of an ordinary offence of the same description." "If you happen to be born a gentleman, you may conduct yourself with comparative impunity like a blackguard."[18]

Young gentlemen of that era were certainly handy with their fists, and rarely tender of the rights of their social inferiors. Parnell was famously forced to leave Cambridge in 1869 after becoming involved in a fight with a couple of drovers. Less well known was an unpleasant episode at a Wicklow hotel later that summer, in which he harassed some English tourists (presumably from the despised middle class) and blows were exchanged.[19] By contrast, in the medium term, King-Harman's career was not affected by his brief incarceration in Coldbath Fields, not least because he did not have one. Unfortunately, the ever-resourceful Tim Healy unearthed the episode in 1887 and turned it against the Unionist government's proclaimed belief in law and order.

However, at a personal level, King-Harman's loutish behaviour probably caused him considerable embarrassment. He was engaged to be married to Emma Frances Worsley, daughter of a North Riding baronet, and the wedding had been "arranged to take place in Yorkshire early in June" – at precisely the time he was forced to answer to the Westminster magistrate.[20] The couple were relatively young – King-Harman was 23, a year older than his bride – and as his youngest child, Emma may well have been the object of Sir William Worsley's special affection. We may guess that the errant bridegroom had some awkward conversations with his future father-in-law, not to mention with his fiancée. To make matters worse, to delinquency was added bereavement. Emma's brother, thirty year-old Arthington Worsley, seems to have been suffering from a painful degenerative disease – as usual, the medical information is opaque – and was taking the waters at the spa town of Malvern. On 3 June he died of "neuralgia which suddenly attacked the heart".[21] Accounts of the Cremorne riot include references to the arrival of a telegram summoning King-Harman to a deathbed – a message that some felt was suspiciously convenient – and it was evidently the death and funeral of brother Arthington that delayed the hearing of the second charge arising out of the 28 May affray until the middle of June. There is never a good time to be sent to prison, but King-Harman had undoubtedly managed to choose a spectacularly bad one.

After a two-month delay, his marriage to Emma took place in late August 1861. A daughter, Frances (known in the family as Fay) was born in 1862, and a son, Laurence, followed in 1863.[22] With only one son, King-Harman's own dynastic ambitions were dangerously at risk to the fragility of Victorian life: Laurence's early death in 1886 would be a severe blow. Still, the eighteen-sixties were an easy decade for King-Harman, a life of Dublin clubs and country pursuits. As the family history admits, he "seems to have had no occupation from the time of his marriage" until 1871, when his father put him in charge of managing the Rockingham lands.[23]

However, while King-Harman was leading a frivolous life, Ireland seemed on the verge of revolution. In 1867, there were fears that Newcastle would be attacked by Fenians, and the experience of a lieutenant who had commanded riflemen helped turn the mansion into a stronghold. Newcastle would be defended by a force of 75 to 80 "good steady men", armed with grenades and guns, trained to load and fire in relays, their womenfolk organised to supply ammunition.[24] The attack never came, but, as a soldier, King-Harman felt some sympathy with men who were prepared to fight for their beliefs. Even after his re-emergence as a diehard Conservative, he hailed the Fenian rank-and-file as "honest men misled by designing knaves". During the 1883 Dublin by-election he admitted that as "a student of Irish history", he could "still read with something of pride and sympathy of those who in the days of old carried the flag of rebellion in this country". In one of his last explosions in the House of Commons, he turned on his Irish tormenters to claim that "there was more honourable feeling among Fenians than among those who sat below the Gangway opposite". As a candidate in the Longford by-election in 1870, he had called for the release of Fenian prisoners, and he was said to have privately subscribed to help support their families. But the crisis of 1867 provided an early example of the quirky and anecdotal process that led him to adopt sweeping if shallow political opinions. It was a "remarkable thing", he told the House of Commons twelve years later, that a rumour swept his locality in 1867 that "when the Fenians took possession of the country they would parcel it out in farms of 10 acres each; and, therefore, every man who held 11 acres was an opponent of Fenianism." Without questioning either the canard or the generalisation that supposedly followed from it, he concluded that peasant proprietorship would bring stability to the Irish countryside, and began to consider land purchase schemes.[25] Within three years, a similar series of staunch shibboleths catapulted him to a prominent place in a new movement for Irish self-government.

In 1874, King-Harman was at the centre of a dramatic episode that briefly threatened to be fatal. In mid-April, he attended a race meeting in Sligo town, staying at a local hotel. Around midnight, he was chatting and, no doubt, drinking with three friends in a private sitting room when they heard a commotion in the public bar, which, at that hour, was officially closed. Charles Clancy, a barber, and his brother Henry, a hairdresser, had forced their way in, demanding to be served. When a barmaid refused, she was called "improper names". King-Harman and his friends "remonstrated" with the intruders, and then helped staff hustle them into the street. Outside the hotel, Charles Clancy produced a knife, slashed two of the men and stabbed King-Harman. He was perhaps fortunate to have suffered a broken rib – some indication of the violence of the attack – since if the blade had penetrated deeper, the wound might well have been fatal. As it was, his life was "in great danger" for several days. There were fears that infection would set in, and the victim himself asked that prayers for his recovery be said in local Protestant churches. It would be two weeks before he was pronounced to be "out of danger".[26] The sequel, at the Sligo assizes in July, was an anticlimax. Brief press reports suggest that Clancy's trial was a simple recitation of the facts: he could hardly have afforded ingenious legal representation, and a plea of self-defence might have been dangerously provocative. Yet, surprisingly, the jury failed to agree a verdict, the jurors were discharged and so, it would seem, was the accused, since there is no report of any retrial. King-Harman was in his Home Rule phase, and the Freeman's Journal had referred to him as "this gallant and patriotic young gentleman", but perhaps there was some feeling among the jurymen that Clancy had been subjected to disproportionate force.[27] It seems unlikely that the stabbing was linked to the breakdown of King-Harman's health after 1885.

Home Rule King-Harman shared in the widespread Protestant outrage at the disestablishment of the Church of Ireland in 1869, which led almost as a reflex action to the formation of Isaac Butt's Home Government Association [HGA] the following year.[28] He was not only a founder member, but an active participant, chairing public meetings (possibly a mistake, since his Conservative politics encouraged the conspiracy theory that the HGA was "a Tory dodge"[29]), and taking an active part in by-election campaigns, where his bulk, courage and boxing skills were exceptionally valuable. Even before the founding of the HGA, he was in the thick of the December 1869 Westmeath by-election, flooring opponents "like ninepins" on behalf of the veteran Young Irelander, John Martin, in opposition to a rival landlord family, the Greville-Nugents, whose treatment of their tenants he vigorously condemned.[30] When the result was overturned, because of bribery and intimidation, King-Harman came forward himself to contest the second by-election, in May 1870, doubling John Martin's vote against another Greville-Nugent candidate.[31] Another opportunity soon occurred. Parnell would famously make his first political impact by contesting the 1874 County Dublin by-election for the Home Rule League. When a vacancy occurred for Dublin City four years earlier, the HGA faced the same embarrassing challenge: to fail to contest the capital city would be a terrible confession of weakness. King-Harman came forward as their standard-bearer, to be honourably defeated by 4,468 votes to 3,444.[32] He put himself forward as a possible candidate for Roscommon in 1873, and for Athlone in 1874, before finally securing an unopposed return for County Sligo in 1877.

"I stand here as a true Irishman", King-Harman told a Conservative rally at Dublin's Rotunda in 1883.[33] "Colonel King-Harman is himself more thoroughly Irish than any original Celt," said Vanity Fair in 1886. It riled him that he was in the process of being redefined out of the country altogether. "He and others were denounced as Saxons," he complained during the debate on the Home Rule Bill. "They, and their ancestors, had been 350 years in Ireland, and yet they were spoken of as 'aliens', and were to be kicked out of the country. Who were the Irish? He should like very much to know."[34] Pride in his Irish identity underlay his support for Home Rule, the belief, as he put it during the Dublin by-election, that "Irishmen should be and are competent to manage their own affairs…. Englishmen cannot govern us because they are ignorant of our circumstances." He spoke of frequent conversations with English MPs, who admitted their inability to understand Irish issues, but nonetheless mechanically voted against remedial measures.[35] Like Parnell, he was proud that his forebears had resisted the "iniquitous" Act of Union. In the Longford by-election, he claimed that "long before" he entered politics, "I had considered, not only the necessity, but the possibility, of obtaining for our nation our only chance of prosperity – Irish government for Irish affairs." He repudiated the slander that he was "determined to get into Parliament at any cost", describing the expenditure of "time, energy, and labour in a British Parliament" (not to mention the expense) as conferring an "extremely problematical honour".[36] "I am not a Gladstone man; I am not a Disraeli man", he insisted to the voters of Longford, calling himself "a supporter of every measure calculated to improve my country."[37] Speaking in Roscommon three years later, he reiterated his independence. "He belonged to no party. In fact, he did not want to interfere in English politics at all." A.M. Sullivan advised King-Harman to repeat this formula at the Sligo by-election in 1877, but its obvious unreality led it to be quickly thrown back at him.[38] Nonetheless, it was an early indication that his political stance would diverge from the parliamentary guerrilla tactics favoured by Parnell.

King-Harman saw the Protestant backlash against disestablishment as an opportunity to construct a united front in Ireland. "A great change has taken place in popular opinion, especially amongst those classes who, a few years ago, would have been most hostile to the nation, that Irishmen alone are qualified to manage Irish affairs. … we want more than the fusion of the Catholic and the Protestant elements – we want more than the cordial concurrence of the landlord and the tenant parties – we want a purer patriotism still." "No nobler utterance has cheered our country for weary years", purred the Nation. But there was a hidden catch in his plea "that each and all of us should cast aside personal ambition, and be content to work for the common weal. … let Protestant and Catholic, landlord and tenant, peer and peasant unite, and England must grant our just demands, for Ireland United is Ireland Free." While King-Harman was prepared to respond to the Catholic bishops over education and remedy the grievances of the tenants, fundamentally he envisaged an Ireland where the substantial concessions necessary for cross-community harmony would be made by others in their unquestioning deference to Ascendancy rule. In 1870, that assumption was still defensible: even the Nation believed that the Irish people would rather follow their landlords "than any other leaders on earth, if they would but be leaders, and lead, not for a class, or a party, or a creed, or a section, but for Ireland".[39] "His ambition was to see an enfranchised Ireland in which the 'gentry' would be the natural leaders of the people," wrote a sympathetic critic at his death. "He could not see that the 'gentry' themselves made it impossible, and, therefore, he threw in his lot with own caste."[40] Indeed, King-Harman was all too ready to assume that his call for social harmony was in itself enough to achieve ecumenical peace. During the 1871 Westmeath by-election he proclaimed that he was "proud" as "a Conservative, Protestant gentleman" to share a platform with the local Catholic bishop and his priests of the diocese and "to thank Heaven that at last his fervent aspirations had been realised and that religion no longer divided them."[41] This was the man who would try to bar his own daughter from marrying a Catholic.

King-Harman's use of simplistic imagery makes it difficult to deduce precisely what he hoped an Irish parliament would achieve. Pointing out that Roscommon would not wish its county business to be transacted by Longford no doubt reassured his own neighbours of the homeliness of Home Rule, but it hardly reflected a mature acceptance of the possibility of being outvoted in a self-governing legislature.[42] By contrast, likening Ireland to "a barrel with two leaks in it", one represented by emigration, the other by absenteeism among the landed classes, was a striking metaphor. No doubt, during the Dublin by-election, the claim that absenteeism was "killing the country" appealed to shopkeepers and property owners in the capital. "Look at your streets, comparatively deserted – your public park, with scarcely a carriage to be seen driving in it, and the blinds pulled down on the windows of the public squares, not a soul living in the houses and knockers never touched." But, even when seasoned by anti-English invective, his panacea, "home legislation", was not very persuasive: it would "bring back money to the country, which will restore commercial prosperity and bring among us all those means of wealth by which England flourishes, and by fraud and unfair commercial treaties she has denied to Ireland."[43] While it was reassuring to learn that he had grown out of vandalising doorknockers, it was not clear whether he expected a self-governing Ireland to embrace tariff protection (as Parnell wished), leaving a lack of clarity on a major issue. By 1877, King-Harman had come to believe that "the question of absenteeism is exaggerated", yet he offered no alternative economic case for the restitution of self-government.[44]

King-Harman was equally imprecise about the form of self-government that he supported. As early as the Longford by-election, advanced Nationalists criticised the allusions to Home Rule in his election address as "vague and unsatisfactory".[45] In his sole parliamentary speech on the subject, in 1877, he avoided detailed commitment, not least because he was seconding a motion which merely asked for an enquiry.[46] He acknowledged that there were "many Irishmen of considerable intelligence and influence who would limit their demand by saying – 'Give us a local commission for Ireland who can legislate for us on such subjects as Railway and Gas Bills' but he did not acquiesce in that limitation—far from it." He insisted that he wished an Irish legislature to deal with "purely Irish matters" repudiating "in the strongest manner any wish to interfere with Imperial questions", but he made no attempt to define the division between the categories. He drew a firm distinction between Home Rule and "separation from England", reminding the House of Commons that "the first body of men who spoke up for Home Rule were principally Protestant Conservative gentlemen, who would repudiate with scorn the idea that they desired to separate from England, and who, if repeal of the Union were offered them, would refuse it at once, because they were aware that by accepting it they would be doing themselves a most material injury."[47] The Disraeli government's chief secretary for Ireland, Sir Michael Hicks Beach, pointed out that his "repudiation of a desire for Repeal… was coldly received" by other Home Rulers.[48] King-Harman's notional allies would have reacted even more negatively had he revealed his belief that Home Rule would in fact create a new and deeper relationship within the United Kingdom. "Home Rule meant not separation from England, but real union", he had told an audience at Drogheda in 1871. "Let their English brethren but give them fair play, and they would find that Irish hearts were warm, and Irish arms were strong, and when the day of tribulation came, instead of being a thorn in their sides, they would prove a help."[49]

Much of this might be dismissed as an idiosyncratic construct of self by an assertive character who sought to reconcile his proclaimed Irishness with his personal relationships – a Scottish mother, an English wife, the experience of an English public school and a British regiment. But Roy Foster has warned against the simplistic dismissal of the followers of Isaac Butt as merely gentlemanly dilettantes, destined to be trampled underfoot by the march of Parnellite nationhood, arguing that, in the eighteen-seventies, there was still scope for a devolution settlement that would not undermine Britain's imperial strength. King-Harman was right to warn the House of Commons against the assumption that that refusal even of a commission of enquiry to examine its possibility would put an end to Home Rule: "so far from it being squelched or stopped, it would grow up into a larger and more awkward question".[50] It did indeed mutate, driving him out of its ranks.

A dramatic episode in the House of Commons in April 1878 drove a wedge between King-Harman and the wider Nationalist movement. Backed by Parnell, Frank Hugh O'Donnell attempted the courageous task of persuading MPs that the recent assassination of the Earl of Leitrim was not a harbinger of agrarian warfare. Lord Leitrim's defenders portrayed him as an eccentric landlord who was punctilious in upholding his rights. In reality, he was cruel and capricious, and widely suspected of sexual exploitation. O'Donnell's use of the term "debauchery" provoked a protest from King-Harman, but as the member for Dungarvan purported to be discussing a hypothetical situation, the Speaker allowed him to continue. However, an allusion to an episode that was widely believed among the Irish people to be true proved too much for his colleague from Sligo. O'Donnell referred, again ostensibly in hypothetical terms, to a tyrant who had placed "the alternative of eviction or dishonour before the peasant girls on his property", and who "when his infamous advances had been slighted … had carried out his threat of eviction". King-Harman, described by one unfriendly newspaper as "goaded to frenzy by the attack on the manners and customs of the aristocracy", leapt to his feet and announced that he spied strangers. The Freeman's Journal condemned him for using this "obsolete privilege" to drive journalists from the galleries, ominously branding his initiative as "an ill service for a Home Rule member", the more so as King-Harman himself was "we believe, a good landlord" – possibly the last favourable acknowledgement of his paternalist credentials from the Nationalist camp. Although the debate continued in closed session, King-Harman's gesture ensured even greater publicity for O'Donnell's carefully laundered charges. It also cost him much of his earlier popularity. When Parnell attacked him at a meeting of Irish exiles in Manchester a few days later, there was "loud hissing" at the mention of his name.[51]

By June 1878, King-Harman was under attack in his own constituency. The influential weekly Nation published a critical letter from "A Tobbercurry Man". (It sometimes seemed that this small settlement had as many names as people: it was also spelt Tobercurry and Tubbercurry.) The writer was almost certainly the Fenian hotel-keeper, Patrick Sheridan, who would soon emerge as a key Land League organiser. In 1882, an over-confident Parnell would rely upon him to pacify the west of Ireland as part of the Kilmainham Treaty settlement, but Sheridan caused him great embarrassment by fleeing the country after the Phoenix Park murders. Sheridan probably hoped to be elected MP for Sligo himself and, although the ambition was implausible, he chose thinly garbed anonymity in the knowledge that the hand that wields the dagger rarely wears the crown. The tactic adopted in the letter was subtle, and characteristic of Sheridan's deviousness. While condemnatory of King-Harman's record in Parliament, it directed its principal fire against Canon John MacDermott, a prominent priest who had supported his candidacy at the previous year's by-election. MacDermott crushingly replied that his assailant well knew that he had recently moved to a parish in Mayo, and hence was barred by simple courtesy from lecturing the people of Sligo. However, Tobbercurry Man's challenge had the intended effect. Canon MacDermott let rip, damning King-Harman's votes in Parliament as "nothing short of treachery" and the man himself as "a huge political humbug".[52]

King-Harman was roundly defended by one of his tenants, James Quinn of Erris. The Nation declined to publish much of his letter because of it was too abusive, but Quinn's attack on Canon MacDermott is a refreshing antidote that the assumption that Catholic Ireland was priest-ridden and crushed into submission by the Church. "It is sad to see one whose mission is to cultivate peace and good-will amongst men, taking up charges against a man without one particle of truth to support them." King-Harman, Quinn insisted, "supports Home Rule by his influence, his vote, and his purse. He not only advocates tenant-right, but practically carries it into effect."[53] To some extent, the attacks on King-Harman were unfair. He had spoken in support of Home Rule, and was evidently sincere in his support for Catholic education, especially the widening of opportunities for study at university level. In June 1878, he told the Commons that "the Catholic youth of Ireland were not placed on a fair footing with their Protestant countrymen – that they had to start in the race of life unfairly handicapped and weighted, whereas it was the duty of the State to deal equally with all classes." To the objection that support for Catholic colleges this "would place education in the hands of the priests", he insisted that the Irish people and their priests simply demanded "a better system than now existed, in order that the children might receive a comprehensive and not a dwarfed and bigoted education." The clear implication of his argument was that the middle-class Irish Catholic laity would place limits on the influence of the Church. "No sane Irishman, possessing education himself or appreciating the advantages of education, would do what the opponents of Catholic education in Ireland asserted would be the effect of the proposed change, and allow the entire education of the rising generation of the country to be handed over entirely to the priesthood without any supervision on the part of the State." It was a sign of the hostility generated by the Lord Leitrim episode that Dublin's two leading Nationalist newspapers truncated their reports to make it appear that he had delivered a personal attack on the integrity of the priesthood.[54]

Later, when King-Harman occasionally defended his conversion to Unionism, he used the classic argument of many defectors from a cause: he had not abandoned Home Rule, rather it had moved away from him. During the debate on Gladstone's scheme in 1886, he insisted that the Home Rule leadership of the early 'seventies "was composed of a very different class of men from those to whom the Prime Minister now proposed to hand over the government of the country. They were leading merchants, magistrates, bankers, and other men who had a great stake in the country, and one and all would have scouted the idea of separation." But in one of his last parliamentary interventions, King-Harman honestly acknowledged that he had been a "hot-headed young man" who misread the course of Irish nationalism: "he was one of the few who had laid down money, and had sacrificed political and personal friendship in the hot days of his youth, on the altar of Home Rule, because he then believed that there was honesty among those men who were agitating for Home Rule, and that it was only when he found that there was no honesty among them that he found himself obliged to reconsider the ideas of his hot youth." Unionism was content to forgive the sinner who had seen the light. Even Edward Saunderson, the most rigid of Ulster Conservatives, accepted that "no one could deny that Home Rule in former times was a very different thing from what it is now."[55] As King-Harman himself put it in 1882, the original Home Rule movement "might have been foolish, but its intention was good."[56] His former allies were less charitable.

Of course, King-Harman's conversion to Unionism was made all the smoother by the fact that he was already a Conservative, one of handful of the Home Rulers of the 1874 Parliament who sat on the government benches. Hicks-Beach regarded him as "really a staunch supporter" of Disraeli's ministry, which conferred costless distinction upon him: an honorary colonelcy and the office of lord-lieutenant of County Roscommon.[57] But his political affiliation was entirely consistent with membership of the Home Rule Party in the eighteen-seventies, which required merely a pledge, as King-Harman put it in 1873, to support "Home Rule and nothing but Home Rule". Indeed, he sarcastically dismissed proposals for a wider and more binding programme with what he regarded as a satirical absurdity: why not "pay your representatives and dismiss them after a week's warning as you would any other servant"[?][58] He remained to the end a supporter of Isaac Butt, although he seems to have stopped attending the party's occasional meetings by 1878. There would clearly be no place for him in the Irish Party of the eighteen-eighties, alongside Parnell's paid subordinates.

Parnell's condemnation of King-Harman at Manchester raises an intriguing question: what were the relations between the two during their brief period as fellow Home Rule MPs? They may not have encountered one another much before King-Harman entered the House in 1877: there was eight years difference in their ages, and King-Harman had been at his most active in the Home Rule movement in the early years of the decade, before Parnell entered politics. Nonetheless, they belonged to the same Ascendancy world: Parnell's aristocratic Wicklow neighbours, Viscount Powerscourt and the Earl of Carysfort, had been King-Harman's exact contemporaries at Eton.[59] Yet their political trajectories soon diverged. King-Harman was elected for County Sligo at the beginning of the session in which Parnell explicitly claimed that the party pledge did not preclude him from active involvement in non-Irish issues, joining a small group who engaged in parliamentary obstruction. In 1879, King-Harman quoted a comment made to him about a fellow MP who was "at that time rising into some public notoriety … I was told he was a hard hitter, a good block, a bold twister, but that he always quarrelled with the umpire."[60] This may have been a roguishly friendly allusion to Parnell – Hansard unfortunately tells us nothing about tone – probably by implication drawing upon tales that the young Parnell had unsportingly exploited the Laws of Cricket while captaining a local team.[61] Any pretence at mutual amiability was soon discarded. Parnell contemptuously dismissed the suggestion that he should contest County Sligo himself at the 1880 general election, indicating that King-Harman was beneath his notice. By 1882, King-Harman branded Parnell as an "arch traitor", which was a more serious charge than merely bending the Laws of Cricket. In 1886, he assured the House of Commons that loyalists "would never rebel against Queen Victoria, but they would never swear allegiance to King Parnell."[62] For his part, only once had Parnell perhaps demonstrated what may have been a favourable awareness of King-Harman's existence. In a conversation with William O'Brien in 1878, he condemned the Irish landlords as a class for their lack of achievement. The only thing they could boast about, he insisted, was their foxhounds, although he added, "perhaps … in the Roscommon country, their horses."[63] The throwaway comment has always seemed puzzling, since Parnell had no known associations with the county, and may not even have set foot in Connacht until late in 1877. One possible explanation is that the two country gentlemen MPs had chatted about the only subject of shared enthusiasm, horse breeding.[64]

The King-Harmans as landlords to 1879 The 1879-81 Land War completed the divergence between the political trajectories of King-Harman and Parnell. Parnell owned less than 5,000 acres, which yielded a gross rental of under £1500 a year. King-Harman functioned on a grander scale: 73,000 acres and a rent roll of £40,000 a year.[65] However, Parnell's income was so eroded by mortgages and annuities that his Avondale estate produced almost no net income. He responded by establishing a sawmill and developing quarries. In effect, Parnell turned himself into a building trade entrepreneur, which explains why, as a businessman, he wanted tenants to enjoy the benefits of the improvements they made to their holdings. But King-Harman's position was also less impressive than it appeared. His princely income was burdened by encumbrances amounting to annual charges of about £32,000, reducing his £40,000 gross income to a net figure of around £8,000. Unfortunately, no records survive for Parnell's business activities, and his contemporaries supplied little information, since they usually conformed to contemporary snobbery by deriding his involvement in 'trade'. However, it seems likely that by the late eighteen-seventies, he was making enough money selling sawn timber and building stone to make his rental income virtually irrelevant. Consequently, he may not have been unduly inconvenienced by demands for rent reductions, or even by refusal to pay altogether: he joked in 1882 that his tenants were "standing by the 'No Rent' manifesto splendidly."[66] By contrast even the short-term disruption of the Land War spelt disaster for King-Harman. Worse still, the 1881 Land Act (more accurately, the land courts that it created) permanently reduced his gross rental receipts by twenty percent, thus exactly wiping out that net annual income of £8,000. By the time of his death, it was well known that King-Harman was in financial difficulties.[67]

The logical solution for both men would have been to liquidate their encumbrances by selling their non-demesne properties, preferably to their tenants. Parnell did attempt to sell his Avondale estate in 1883, but his tenants were so horrified at the prospect of losing his gentle overlordship that they launched a subscription to bail him out, which grew into the national Parnell Tribute. It is likely that only through a large-scale State-funded purchase scheme could King-Harman's tenants have afforded to make the transition to peasant proprietorship. Even if they had been willing to embrace such a novel idea, no such funding was available in his lifetime, although the 1885 Ashbourne Act was a pointer to a future that neither King-Harman nor Parnell lived to see.[68] There were, too, economic and cultural differences stemming from locale which helped shape their differing responses.[69] Parnell was a relatively minor player in a county which, by the admittedly modest standards of post-Famine Ireland, had a reasonably sophisticated economy, benefiting both from its proximity to the Dublin market and by its ability to trade with Britain. The stagnation of the city centre described by King-Harman was caused not only by the flight of the landed classes to Britain, but had also happened because Dubliners themselves were decamping to comfortable (and newly built) Victorian suburbs. Westminster's inability to make time to pass enabling legislation for the upgrading of Arklow harbour provided Parnell with one of his first Home Rule causes. By contrast, King-Harman was one of the two largest landowners in a predominantly agricultural county, with much of its farming close to subsistence levels, and relatively few resident landlords to provide leadership and support. As a result, a form of regional chieftainship devolved upon him, with broad responsibilities towards tenant welfare that he dutifully shouldered during the Famine winter of 1879-80.[70] However unrewarding financially or – after 1880 – emotionally was the role of paterfamilias to an increasingly unappreciative peasantry, King-Harman no doubt felt tied to his inherited destiny. No such constraint affected Parnell.

King-Harman inherited two estates at his father's death in 1875, Rockingham, with 42,000 acres of land in Roscommon and Sligo, which he had been managing since 1871, and Newcastle, with 30,000 acres, mostly in County Longford.[71] Put in the simplest terms, Rockingham was burdened with over £200,000 in mortgages, and "belonged more to the money-lenders than to the [King-]Harmans".[72] The mansion, one of the finest in Ireland – in Edwardian times, it briefly became the viceregal country residence – was also massively expensive to maintain. In effect, Rockingham was kept afloat by Newcastle, which had been well run by the paternalist King-Harman senior since he had inherited it 1838. Although he considered selling Newcastle in order to wipe out the accumulated debt on Rockingham, King-Harman senior could not part with his home.[73] In 1874, he entailed its succession to King-Harman and his son's male heirs, providing for it to pass to his own younger sons in turn should that line fail.[74] The death of King-Harman's heir, still a bachelor, in 1886 threw the future of Rockingham still further into doubt. When they took over in 1871, the King-Harmans attempted to put Rockingham on a business foundation. Rents seem to have been under-collected by over £2,000 a year. The accumulated debts were consolidated to reduce interest charges. Like Parnell, and at almost the same time, they began the aggressive exploitation of the timber on their own demesne, although resource development did not replace reliance upon rents.

Although it was subsequently argued that average figures obscured anomalies and injustices, they may throw some light on the pressures faced by farmers on the King-Harman estates.[75] The 1,386 tenants in Roscommon and Sligo occupied farms of about 30 acres: average holdings were slightly higher in Sligo (34 acres) than in Roscommon (29 acres). They owed annual rents of £18.1 in Roscommon and £14.5 in Sligo. County Longford tenants of the Newcastle estate also held farms of about 34 acres, and paid average rents of £17.3.[76] There are some puzzling inconsistencies in these figures. The difference between the two counties in the Rockingham portfolio is not easily explained: the average Sligo holding was slightly larger but paid less. Of course, average figures do not account for quality of land. As King-Harman explained in 1881, "the hillsides can only be worked by spade labour," making necessary smaller upland farms of around fifteen acres.[77] The statistics are probably also complicated by the fact that some of the acreage was bog land, of almost no use for farming, but complicated by a long-running dispute between King-Harman and local farmers over the right to cut turf for fuel.[78] Agriculture in Leinster was generally regarded as more advanced and more prosperous than in Connacht, and King-Harman himself frequently drew contrasts between his two estates in his evidence to then royal commission on agriculture in 1881.[79] Yet his rents in Longford averaged around ten shillings an acre, twenty percent below the rates charged in Roscommon. Inconsistencies like these would provide the land courts with opportunities to slash rents altogether.

It is virtually impossible for historians a century and a half later to assess how far these rents were a burden, and arguably it may be presumptuous even to try. J.J. Lee, no apologist for the Ascendancy, dismissed "the argument that excessive rents prevented accumulation of capital" before 1879, while the slow pace of rural change after 1881 confirmed that "rents had not proved an intolerable disincentive previously".[80] While the general picture may be reconstructed, at a practical level it does not seem that individual farm accounts have survived. More to the point, posterity does not have to find the cash. The massive inflation of the intervening period makes it difficult to appreciate today what an annual outlay of £18 might mean for a family, and how it would relate to overall prices. One possible comparator might be the salary of a National [primary] schoolteacher, which, in 1876, was £32 a year for a man, £25 for a woman.[81] The indicator tells something about the value of money, but noting that the average King-Harman tenant paid half a schoolteacher in annual rent does not tackle the subjective question of whether farmers felt the burden was reasonable.

At the very least, rent statistics remind us that even the most self-sufficient of family farms had to operate within a wider money economy. Not only were tenants dependent upon successful harvests and buoyant prices, but their income stream came in annual floods. For much of the year, they were necessarily dependent upon credit, reliant upon the business acumen of shopkeepers and dealers in supplying goods against subsequent payment. King-Harman argued that it was not landlordism that hurt the rural west of Ireland, but the expansion of debt that was, ironically, consequent upon a gradual increase in living standards since the region had recovered from the Famine of the eighteen-forties.[82] "For several years past," he wrote in 1879, "credit has almost been forced upon the people; the Gombeen man, or village usurer, has woven his webs in every neighbourhood, and shopkeepers have vied with each other in giving long credit for frequently inferior and adulterated articles".[83] The banks were even worse offenders, extending their branch networks into small towns and advancing money, often charging over ten percent in interest. When the harvest failed, the structure seized up, "not a shilling will be advanced, not a mouthful of meal or a bag of manure will be supplied without ready money."[84] Arguably, King-Harman confused the symptoms with the disease. No doubt, there were grasping merchants,[85] but many small-town shopkeepers had close links with the rural community: it may well have been a family farm that had supplied the capital required to get into retail trading. One of the striking features of the Land War is that it did not pit country against town: Land League officials were often urban residents, and few market centres in the west of Ireland were much bigger than villages anyway.[86] In the crunch winter of 1879-80, it was obvious that something had to go, and the farmers had little hesitation in turning upon their landlords, not their creditors. Perhaps rather than focusing upon the indebtedness that they encouraged, King-Harman should have noted that the shopkeepers had expanded opportunity by extending credit in the first place. His disdain for the "inferior and adulterated articles" that he claimed they supplied contained a hint of disapproval that the supposedly simple peasantry should be seeking inappropriate material comforts. His insistence that the tenant was a "simple man" who "deserves to be more protected from the shop-keeper and the gombeen man than from his landlord" was patronising and self-serving.[87]

King-Harman senior had been praised as "an excellent landlord". Even the Freeman's Journal praised his "untiring and unabating exertions" for local improvements in County Longford. For instance, he presided at the monthly meetings of the Ballymahon Farmers' Club, where cultivators of the soil sat through lectures on topics such as "Preparation of manure for green crops" and "Why the Irish are not advancing as other nations".[88] Balfour was later to claim that between 1843 and 1879, there were only 21 evictions from the 850 tenancies on the Newcastle estate. While he did not engage in fancy arithmetic, he clearly implied that one failure for every 1,457 tenant-years – over a period that included the Famine of the eighteen-forties – indicated a benign landlord regime.[89] It was a model that helped inspire King-Harman's attempt to enter politics in 1870. "Tenant-right has been the practice on my father's estates, and I wish to see measure enacted to compel bad landlords to do that which is already being done by the good."[90] Nor was this mere electioneering. In private he delivered "indignant denunciations … [of] the heartlessness of his friends and his family towards the Irish poor".[91] He condemned absentee landlords, but regarded as "the greatest curse in Ireland" their use of absentee agents, "who know nothing whatever of the circumstances of the tenants, who simply send down a clerk with a black bag with orders to take away as much as he can get, and bring it back to Dublin."[92] King-Harman also targeted the "oppression" caused by middlemen, "a most grasping set of men, and they grind the poor terribly". However, it is not clear whether the problem was widespread: he seems to have given at least three outings to one tale of a tyrannical parasite who treated his sub-tenants like serfs.[93]

As already outlined, in 1875 King-Harman inherited not just broad acres but also an insoluble burden of debt. "He was in a better position before he became great landlord." Yet even a cynical observer accepted that he tried to act according to his beliefs. "He used to say that he treated his tenantry better than they were ever treated before, but that was not saying much."[94] By the time he was elected to Parliament in 1877, his enthusiasm for land reform had cooled. True, he criticised the widespread English belief that "the Land Act of 1870 had effectually settled this question", adding that "a vast amount of good that might have been done by the Act of 1870 was left undone and untouched." However, he gave only grudging support to the annual manifestation of Butt's tenant right bill, acting in conformity with pledges he had given during the Sligo by-election – a safe enough strategy, as the proposed legislation had no chance of making progress.[95] He still believed in the principle that a tenant should have the right to sell his holding, but admitted that there were restrictions to its practical operation on the King-Harman estates. "We always allowed that the tenant had some interest in his holding, and we allowed that to be sold, subject to the approval of the estate office, both as to the purchaser and as to the price. I do not allow 'auctioneering'." He had even come to question the assumption that a tenant was entitled to enjoy the full benefit of any improvements he made to his farm, "because if I had not let him that land, I might reasonably have improved it and made more of it."[96] No doubt we should all like to be rewarded for the projects that we might have undertaken. This convoluted assumption was presumably the pained product of the financial constraints in which he found himself trapped. He was hardly more enthusiastic about the possibility of escaping from the prison of landlordism by phasing himself out altogether. While he welcomed the purchase of land by tenants, he envisaged only a restricted scheme, and one in which the incumbent purchaser had to make a down payment of twenty to twenty-five percent of the price. It was precisely this obstacle that had limited the uptake under the purchase clauses of the 1870 Act. "The work would, of course, have to be carried out gradually – say, at the rate of 1,000 tenants per annum". It is doubtful whether the interests of the purchasers really weighed very heavily with him: "the landlords were also much interested in the subject … they would be very willing to have their outlying property taken off their hands in the way proposed."[97] Fundamentally, land purchase was another noble idea that simply did not work. "I am a strong advocate for it on principle, but whatever practice I have seen of it is bad."[98] By the close of the eighteen-seventies, King-Harman advocated no overarching project capable of resolving the inherent problems of the Irish land system. Like his vision of Home Rule, his conception of property ownership assumed the continuing dominance of the Ascendancy. When the country was engulfed by crisis between 1879 and 1881, others would seize the initiative, imposing their own radical alternatives both upon the Irish countryside and, subsequently, upon the concept of Home Rule.

King-Harman and the Land War, 1879-1882 The winter of 1879-80 would be King-Harman's finest hour. In his efforts to fight famine, paternalist landlordism showed itself at its best. Ironically, this happened at just the moment when it was about to forced aside, with the clear implication that it would be swept away altogether. There were two principal routes to the attention of Britain's decision-makers, the House of Commons and the columns of The Times. King-Harman used them both. His letter to The Times in mid-November 1879 was one of the first authoritative warnings that "not only dire distress but absolute famine is pending in many parts of Ireland". The letter was poorly structured, repetitive and contained too much minor detail about the recent harvest, but its central message was brutally clear: in many districts, the potato crop had failed ("the potatoes will not last until Christmas") and "the sudden collapse of the credit system … will bring famine to the doors of thousands". "I deem it my duty to let the people of England know that starvation threatens … I see no means of averting a terrible catastrophe if the Government does not intervene".[99]

"On my own property, there will be poverty this winter, but, I trust, no crisis that landlord and tenant working together will not be able to tide over; but it will cost us a sore struggle," he had predicted in November. At the end of December, he repeated his warning that "famine is now at hand", and outlined some of the challenges facing landlords who sought to respond. While expressing embarrassment at being "my own trumpeter", he spoke for landlords like himself who were borrowing heavily from the Board of Works to finance relief projects. In doing so, they were "curtailing their own incomes and burdening their generally heavily-charged estates." High interest rates were a deterrent. "Six-and-a-half-percent is no light sum to face, especially on properties where not one-third of the rent is being paid." Bureaucracy was an additional curse: King-Harman had been compelled to prove his title to the Rockingham estate ten times in support of ten loan applications for specific projects. He regarded the short-term solution as obvious. The legislation that had disestablished the Church of Ireland had diverted some of its endowment into a fund that was "available to meet any pressing calamity in Ireland, and I fail to understand how any national calamity can be more pressing than famine."[100] He followed these missives with a dramatic intervention in the Commons debate on Ireland in mid-February 1880. He claimed that he had not intended to speak, explaining that he had travelled from Ireland to be present "at great personal inconvenience from the post of duty" where he had been "engaged in taking his part in the relief of the distress existing in Ireland, trying his best to render the condition of the people as little painful as possible." He spoke, as so often, in defence of his fellow landlords, who had come under attack. "The question before them was a pressing one – the relief of distress, and they ought not to delay its settlement by any discussion as to the policy which had led to its existence." With trade and agriculture depressed in England and Scotland, it was unfair to ask the British taxpayer for help while the Church of Ireland surplus was available for distribution. His appeal to the House to pass the necessary legislation was probably the most influential parliamentary speech that he ever delivered. It was certainly one of the very few to be cited with respectful approval by other MPs as the debate progressed.[101] King-Harman's standing as a result of his benevolent activities was recognised even across the Atlantic. The New York Herald had established its own appeal for Irish famine relief. Its powerful proprietor, James Gordon Bennett, Jr, appointed King-Harman to a four-person committee in charge of distributing the funds.[102]

Of course, King-Harman's attempts to mount relief projects took place alongside the sudden eruption of agrarian insurgency. As the Land League was taking shape in the autumn of 1879, he denounced trouble-makers whose denunciations were "calculated to mislead the people, to injure the cause that they profess to advocate, and to embitter the relations between classes of people whose interests should be bound up together. … The result has come but too quickly. Threatening letters, brutal outrages, and, lastly, an attempt at murder…. The cause of these terribly sad events can only be found in the speeches of reckless agitators." Appealing for the sympathy of a British audience, he more moderately dismissed the Land League campaign as "senseless agitation" – "tomfoolery" would be a later and more bad-tempered description – although he roundly condemned as "heartless traitors those who would set class against class and make political capital out of the sufferings of our fellow-countrymen."[103]

For a brief period that autumn, King-Harman seems to have hoped to be able to contain the emerging land agitation, even agreeing to take the chair at a mass meeting of Roscommon farmers. His intention, in accordance with his belief that the economic problems of the countryside stemmed from the credit network and not the landlords, had been to steer the protest into demanding a general review of rural debt. The breach came on 3 October, when he objected to the resolutions that were to be discussed at the meeting. Three months earlier, he had warned the House of Commons that the small farmers of Ireland were "a class of men who were despondent and rapidly becoming dangerous". In an atmosphere of outrages and anonymous threatening letters, he now argued that such a public meeting could only push "an already suffering people" towards "bloodshed and ruin". Sixty years later, the Folklore Commission found an echo of the local crisis. It was said that "Colonel King Harman had his horses dressed in green", ready to make a grand patriotic appearance at the gathering, when his agent Colonel Robertson warned him that he would be shot if he attended. Nonetheless, with becoming deference, the gathering waited for three hours in the hope that he would turn up.[104] Much of this was at least embellishment and probably outright invention, but the survival of such tales indicated that King-Harman's decision to withdraw from the meeting was remembered as a significant event.

In the winter of 1879-80, King-Harman feared that the widespread distress might trigger "even miserable attempts at rebellious risings". He was unimpressed by the argument that the Land League provided the discipline that contained violence: in July 1880, he conceded that Leaguers enforced their edicts by subjecting backsliders to "hooting and jeering" at markets, but he pessimistically expected that attacks on cattle "will probably be the next thing".[105] Always personally courageous, in one of his last outbursts in Parliament he would indignantly reject an insinuation that fear had driven him into the Unionist camp: "whatever other accusations might have been made against him, he had certainly not expected to be taunted with cowardice." Emerging from his house one morning during troubled times – probably in the aftermath of the Phoenix Park murders – "he found an enormous policeman on his door-step." When he queried the need for a police guard, he was assured not merely that his life was in danger (which he doubted) but that he was being accorded the honour of the same level of protection as Gladstone's cabinet ministers. "For God's sake, do not confound me with any of those people," was his indignant riposte.[106]

The fraught winter of 1879-80 closed with the complication of a general election. The senior member for County Sligo (which returned two MPs), Denis O'Conor, had first been elected as a Liberal in 1868, before rebranding himself as a Home Ruler in 1874. He had done just enough in Parliament to make him acceptable to the advanced Nationalists, but Parnell was determined to win the county's second seat. On his return from the United States in March 1880, the Uncrowned King found that his supporters in Sligo planned to nominate him, believing he was the only Nationalist candidate who could be relied upon to prevent King-Harman from continuing "to insult and misrepresent the constituency". Parnell contemptuously dismissed this as a waste of his energies, arguing that "at least twenty other gentlemen" could defeat the Colonel.[107] He initially suggested T.M. Healy, his secretary during the North American tour, but the choice eventually settled upon his ally Thomas Sexton. Since Sexton was a Dublin journalist and a Waterford man in origin, imposing him upon Sligo ruffled some feathers. Among those offended was Patrick Sheridan, who probably cherished some hopes of the nomination himself. Seven years later, King-Harman was provoked into revealing a strange episode, in which he alleged that Sheridan had offered to use Tory money to split the Home Rule vote by standing himself. King-Harman ignored the initiative, while demoting Sheridan from the status of rascal to that of scoundrel.[108] The trick might even have worked: a similar split in the Home Rule vote enabled his friend Arthur Loftus Tottenham to slip in as the Conservative MP for Leitrim. It would certainly have been worth attempting in Sligo, where, in the event, King-Harman, with 1,250 votes, came respectably close behind O'Conor, with 1,500, and Sexton, who headed the poll with 1,550. Five years later, when Sexton mocked his rejection by the voters of Sligo, King-Harman significantly retorted: "I had the Protestant vote behind me."[109]

During the campaign, King-Harman received a strong endorsement from a perhaps unexpected quarter. Father Luke Carlos was the parish priest at Ballinameen, about seven miles south of Boyle. Insisting that he was in no way dependent upon Rockingham or its owner, he praised the work of King-Harman and his "noble family" during "the terrible crisis currently prevailing". King-Harman himself he even likened to St Vincent de Paul, while the landlord's brother, who the priest thought was a Naval officer, spent his time "going about seeking, miles from home, poor, sick, distressed creatures, to whom he brings relief and comfort." Nineteen landlords owned property in his parish, but "to my poor parishioners, Colonel King-Harman is worth more than the whole lot of them put together." Fr Carlos hoped that he would be re-elected to Parliament. "It would be a mistake not to send such a man to fight for his country's rights and Home Legislature – the good landlord, the friend of the poor, and decidedly a lover of his country."[110] Unfortunately, the electors of Sligo decided not to vote for the man who was doing so much for Roscommon. Soon after, King-Harman told Captain O'Shea that he was "glad of his beating", although Willie O'Shea doubted that he meant it.[111] His three-year absence from Parliament would at least help to screen his dramatic transition to out-and-out Unionism.

Despite his defeat, King-Harman still saw himself as the paternalist suzerain of his tenantry. He acted as an arbitrator in disputes between neighbours and within families, helping them to avoid lawyers and courts. He believed that a resident landlord could have "a good effect" within the local community, even if contact with his neighbours was limited to "a day's partridge shooting". "They are a very sensitive people, and just a little word of encouragement, saying, 'Well, that is a good crop of oats', and so forth, the man will remember it and speak of it years afterwards." It does not seem to have occurred to King-Harman that farmers resented the trampling of his crops by their landlord, his friends and his dogs, nor that they might have dreamed of poaching a partridge in their own pot. But King-Harman felt bound by estate customs himself, for instance accepting an obligation to contribute to house-building: "if a tenant puts up the walls I find the timber and slates".[112]

Through such practices, landlordism had traditionally secured acquiescence: paternalism and deference were two sides of the same coin, for each required the other to function profitably. Deference would certainly have been dented by the Land War, but it may not have been destroyed altogether. One landmark in the Rockingham calendar was the celebration of harvest home, the subject in 1881 of a lyrical letter to the Irish Times from a tenant, John Skeffington, who wanted "all Ireland to know what a kind master we have". Over one hundred men had been entertained to dinner, with the King-Harmans, Saturnalia fashion, waiting at the tables. King-Harman praised his neighbours for their "good and manly behaviour" during the recent agitation, even though they had been "taunted and sneered at by some foolish people". The meal was followed by sports, such as sack races, with King-Harman acting as judge and awarding cash prizes. In the evening, their womenfolk joined them for a dance, in which the landlord's family joined in, with "cakes, punch, ginger beer, lemonade &c" in generous supply. "I shall never forget the day," wrote Skeffington. "God bless the Colonel and his family."[113] The letter was so embarrassingly unctuous that the influence of the Big House might be suspected. However, it has been argued that the Land War interrupted rather than destroyed the "habits of respect" that bound farmers to their landlords. In 1884, King-Harman's tenants – or some of them – subscribed for a portrait of his son Laurence, part of the traditional coming-of-age ritual of the heir.[114] King-Harman continued to persuade himself that landlords like himself were regarded as "good fellows". Indeed, even when his tenants confronted him en masse to demand an abatement of rent, they shouted encouraging phrases like "you were always a grand man".[115] There is no necessary contradiction here. In a universe in which landlords were a permanent fixture, country people were certainly better off with the King-Harmans at their back or even on their back than with most aristocratic or gentry alternatives. Hence they accepted some measure of deference as being in their own interests: 'God bless the Colonel and his family' was a mantra for the safeguarding of themselves. But once legislation created an alternative cosmos in which tenants could in effect dictate the terms of the relationship, and maybe even glimpse the eventual elimination of landlordism altogether, then deference became a negotiable quality, and one that was liable to crumble into nothing.[116]

When, in the summer of 1880, King-Harman learned of the proposed terms of what would become the 1881 Land Act, his initial response was a terse threat that if the measure passed into law, he would close down his relief projects, discharge the labourers employed and leave the country.[117] Contemporaries did not appreciate that an eighteen-stone ex-Army officer was issuing a cry for help: the Pall Mall Gazette condemned his "petulant spirit", doubted that he would act upon his ultimatum and curtly noted that "if he does, he will not take the land with him".[118] Even the prospect of legislation, contested as it was throughout the winter of 1880-81, was enough to disrupt the delicate intertwining of deference with paternalism. The emerging realignment of rural forces was demonstrated in the confrontation between King-Harman and his tenants on New Year's Day, 1881.

It was a Saturday, market day in Boyle, the town full of farmers determined to lobby their landlord. Land League organisers were in the background, but the demonstration seems to have been essentially spontaneous, perhaps something that had grown out of Christmas visiting among neighbours and within the extended cousinhoods of a rural society.[119] King-Harman was given no advance notice of a deputation, but rumours of its manifestation led him to position himself at the estate office that he maintained in town and await developments. Between three and four hundred tenants attended evening Mass, and then marched through Boyle, military fashion, behind two local bands. Confusion ensued when King-Harman stepped out into the street to meet them, to be "received with every mark of respect [,] cheers and waving of hats". The farmers had hoped their priests would speak for them but, while the clergy may not all have shared the enthusiastic admiration of Father Luke Carlos, they were obviously not willing to become involved. Instead, an "elderly man" called Michael McGreevy stepped forward to speak for them. In fact, McGreevy was in his late fifties, no doubt weather-beaten from a lifetime on the land. He occupied 45 acres on the Roscommon-Sligo border, thus possessing both the seniority and the acres to act as spokesman.[120] McGreevy "paid a high compliment to the gallant Colonel as a landlord", condemned his abuse by "paid underlings and mischief-makers" and insisted that they approached him "respectfully". But McGreevy's demand was uncompromising: farm families were "living on three meals a day of yellow stirabout" (thin oatmeal porridge), and they demanded a twenty-five percent abatement of their rent. "Less we will not take," one man shouted.