A New Zealand heritage tour through County Waterford

County Waterford, on Ireland's south coast, has an unusual number of connections with New Zealand. These links are loosely gathered here in an informal outline tourist trail through the county from east to west.

Introduction County Waterford's links with New Zealand form an outline east-west tourist trail in which the connections can be loosely grouped to emphasise particular themes. Waterford City was the birthplace of Captain William Hobson, New Zealand's first governor. The pleasant fishing village of Dunmore East and the Victorian seaside town of Tramore have maritime connections. Bunmahon, on the Copper Coast, is associated with Edith Collier, a New Zealand artist whose work has only become appreciated in recent decades. Dungarvan, the county town, has priests – some of them colourful characters. In the shadow of the Round Tower of Ardmore lies the grave of Major Triphook who, as a junior officer, took part in the New Zealand Wars of the eighteen-sixties. The Blackwater valley in west Waterford provides a number of emigrant stories. The monastery of Mount Melleray, in the hills above Cappoquin, whose monks founded a daughter abbey in New Zealand in the nineteen-fifties – a saga which sparked a major bust-up over alleged ecclesiastical skulduggery.

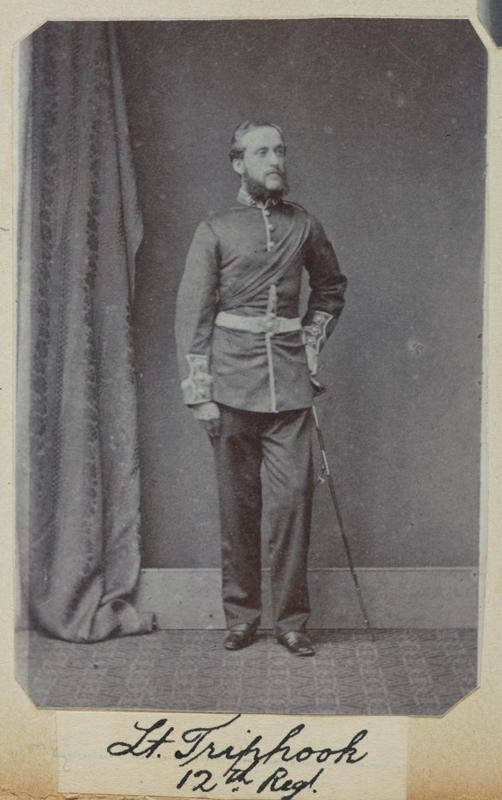

Waterford's New Zealand connections are varied, and some of them are controversial. In particular, Captain Hobson was responsible for the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi, whose ambiguities complicate public discourse in contemporary New Zealand, while the destruction of the village of Te Irahanga, in which Major Triphook took part, is still mourned by Tauranga Māori today. Commemoration is not necessarily celebration. Waterford's links with New Zealand also offer glimpses of the challenges of Irish life in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and perhaps also throw light upon the attitudes and ambitions that helped shape a new society on the other side of the globe.

A study that is aimed at two different audiences at opposite ends of the world will obviously risk either giving some of its readers information they already know, or of omitting background that will leave others puzzled by the significance of the links. Hence the virtual tour is arranged in subsections, some of which can be skipped: for instance, Waterford readers will not be interested in Place and people. Discussion of the two most controversial personalities, Captain Hobson from Waterford City and Major Triphook in Ardmore, is divided into two: a brief overview identifies each person and guides the visitor to the physical connection, while longer More about... notes examine the part they played in New Zealand history, detail that some may prefer to omit. In the happier example of Edith Collier, an outline of her visit to Bunmahon is followed by a more detailed discussion of its context of her life and career. Endnotes and detailed references are omitted, but key sources are mentioned in the text. Most of the stories derive from the Newspapers and Magazines sections of PapersPast, the excellent archival website of the National Library of New Zealand. This is easily searchable by date and by keywords. Supplementary material was trawled from a similar collection, the Irish Newspaper Archives, which may be consulted by arrangement through the branches of Waterford's public library system. Connections that can be seen and visited are underlined, but this does not imply that sites are accessible at all times. I spare readers my brutalist biro cartography, recommending instead Google and other maps that are available on the Internet.

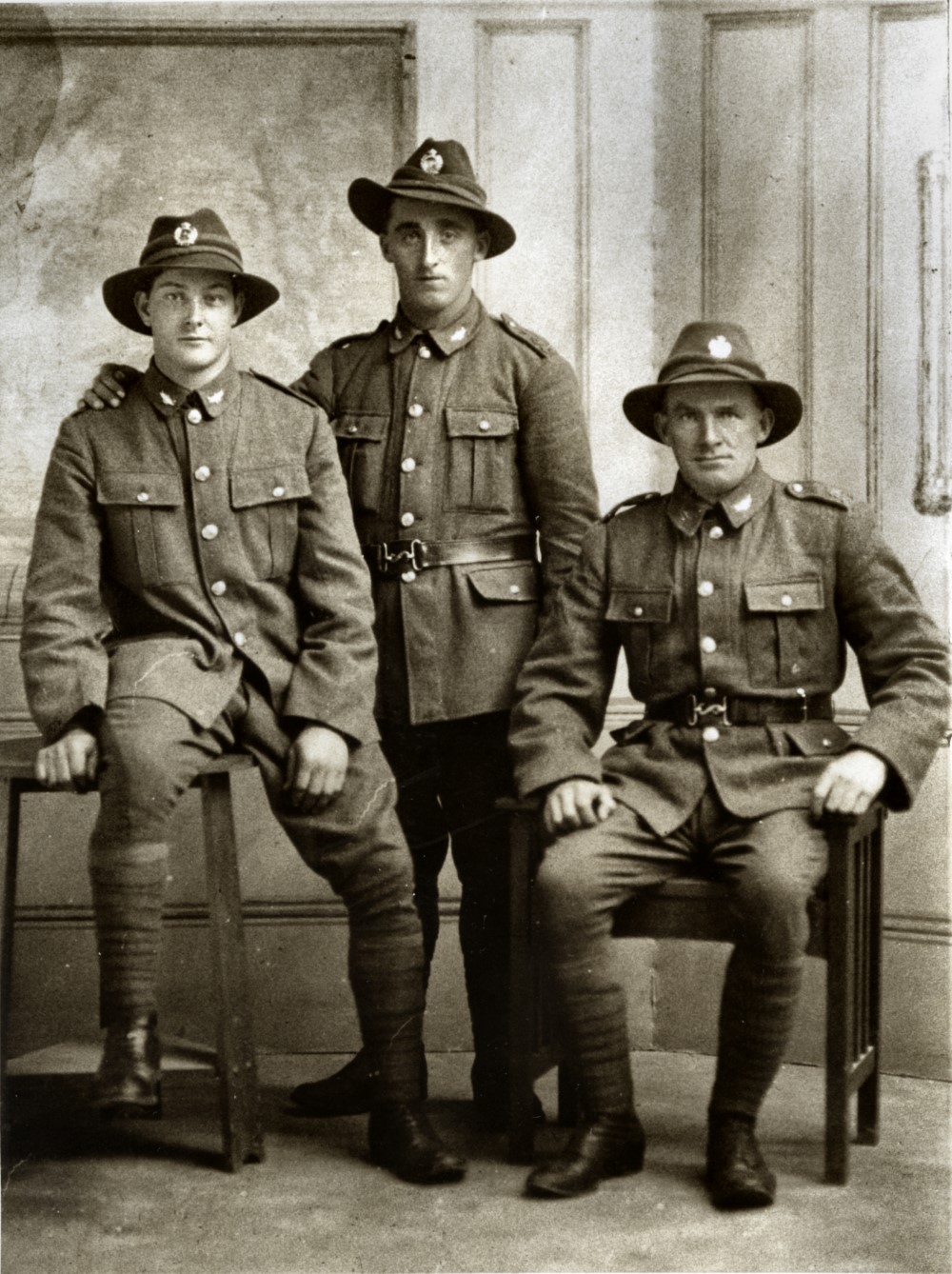

Apparent similarities between the history of the two countries can sometimes be misleading. For instance, in the early decades of settlement of New Zealand, conflict broke out between Europeans (Pākehā) and Māori, usually over control of territory. Formerly known as the Māori Wars, a term now regarded as one-sided, they are generally called the New Zealand Wars or the Land Wars. The main period of fighting lasted from 1860 to 1872, although some would date the start to 1845 and see the conflict as one that continues to the present. In Ireland, the years 1879 to 1882 saw a (generally) non-violent confrontation between tenants and landlords, known as the Land War, which culminated in Westminster's concession of the Land Act of 1881. This recognised the rights of farmers to security of tenure over the land they occupied, and created Land Courts which, from 1882, systematically reduced rents, thereby driving some landlords to bankruptcy and most to welcome State-funded purchase schemes to buy them out. Thus, despite the similarity of terms, New Zealand's Land Wars involved a process whereby the indigenous inhabitants were forced to concede ownership of ancestral territory while, by contrast, Ireland's Land War saw the occupiers of the soil resist landlords imposed upon them as a result of English conquests in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In New Zealand, the divide was ethnic, between Pākehā and Māori. In Ireland, it was predominantly between Catholics and Protestants. The tactical success of Ireland's Land War rested upon the successful mobilisation of a united Catholic tenantry to withdraw co-operation from landlords and resist the imposition of control by the authorities. In New Zealand, Māori were never united in their resistance to the incoming settler population, who were sometimes able to exploit traditional tribal rivalries.

Visitors to Ireland are often puzzled by place-names and local terminology. For instance, Ireland is divided into over 60,000 townlands, a term that is oddly difficult to explain to outsiders. Although the word itself is of English derivation, townlands probably originated around a thousand years ago, originally as property or taxation units. They vary in size, but most are no more than 200-300 hectares in area. Although they have long since lost any administrative function, townlands remain entrenched local identities in the Irish countryside. This is partly because, outside the towns, local roads in Ireland do not have names, and townlands serve as postal addresses. As in New Zealand, Irish place-names are generally derived from the original language of the country, even though few people speak Irish and fewer still live through the language today. (County Waterford has a small Gaeltacht, an officially recognised and supported Irish-speaking district, at An Rinn and Heilbhic, near Dungarvan.) It may be because townland names have been transposed from Irish into English usage that – as will be encountered below – there is sometimes a lack of certainty about their spelling. It is sometimes important to the Waterford-New Zealand story to specify a precise connection with Inchindrisla or Ballyristeen or Knockbrack, however exotic these names may seem to the tourist. (Of course, outsiders can find New Zealand's Māori place-names exotic too. Curiously, some of them have apparent meanings in Irish, even if these are sometimes bizarre: for instance, Rotorua translates as "red-haired bicycle".)

In concentrating upon Waterford's New Zealand connections, I say little about the county's tourist attractions in general – that Waterford City has exceptionally fine museums, that Dungarvan is noted for its restaurants, that Ardmore is an ancient ecclesiastical site. Plaques and gravestones have stories to tell, but it is still worth wandering around Waterford's towns and villages to imbibe the atmosphere that New Zealand's pioneers would have known: the village of Clashmore, for instance, is a little-known gem that has changed very little since Garrett Russell and the Keane sisters left for Otago in Victorian times. It should also be emphasised that Waterford has much more to offer for visitors than can be covered here. The superb Mount Congreve gardens near Waterford City (the exotic display of trees includes a kauri) are worth visiting for their own sake. Neither the forlorn manufacturing town of Portlaw nor its neighbouring mansion, Curraghmore, are known to have New Zealand connections (maybe some will emerge), but they too may intrigue the tourist. Armchair travellers can sample the journey too. Most of the places mentioned have their own websites,while Google Streetview has surveyed the entire county, even climbing into the Knockmealdowns for a glimpse of Mount Melleray Abbey. (The monks, although Trappists withdrawn from the world, have their own Facebook page).

Place and people Waterford is not one of Ireland's best-known counties, and it is also one of the smallest, ranking twentieth in area. It is fair to say that the county hardly forms a natural unit. The right bank of the river Suir forms its eastern and north-eastern boundary, while to the west Waterford stretches without any obvious logic across the valley of another impressive Munster river, the Blackwater. Waterford City, situated at its eastern extremity, functions more as a regional centre for nearby Wexford and south Kilkenny, while west Waterford tends to look to Youghal, across the border in County Cork. Yet there is a strong sense of a Waterford identity, which shows itself in loyal support for the county's hurling team: "Up the Déise!" or (in Irish) "Déise Abú!". (Strictly speaking, the county's nickname, the Déise [rhymes with the Japanese term "geisha"] only applies to its south-western corner.) In 2016, Waterford also ranked twentieth by population, and this despite having the country's fifth largest city straddling its eastern border.

Demography is an important key to understanding Irish history. It is widely known that the Great Famine of 1845-51 was a terrible human disaster, in which as many as one-third of the Irish people either died or fled the country. The impact upon Waterford was certainly severe. The 1841 census counted 196,000 people in the county. Since the trend was upwards, we can be reasonably sure that Waterford was home to over 200,000 men, women and children when the potato crop failed four years later. The next census, in 1851, recorded 164,000 inhabitants, a drop of about one quarter.

What is less well known is that Ireland's population continued to fall. Six and a half million people survived the Famine but, forty years later, there were fewer than five million. The authorities began to count emigrants in 1851, reporting in 1881 that two and a half million people had left the island. In County Waterford, the 164,000 of 1851 fell to 112,000 in 1881, and onward and downward to 84,000 in 1911. Independence made no difference: the city and county were down to 71,000 in 1961. Not until 2011 did Waterford manage to equal its 1881 population. In 1881, 22,000 people lived in Waterford City, leaving 90,000 across the rest of the county, with the 6,000 residents of Dungarvan constituting the only other sizeable urban centre. By contrast, in 2016, almost half the 116,000 population lived in the City – officially, 53,000, but local sources claim an urban area of 60,000, with some estimates of its metropolitan clout as high as 83,000. With a further 20,000 people living in Dungarvan and Tramore, the rural areas of the county are far emptier than they were before the Famine.

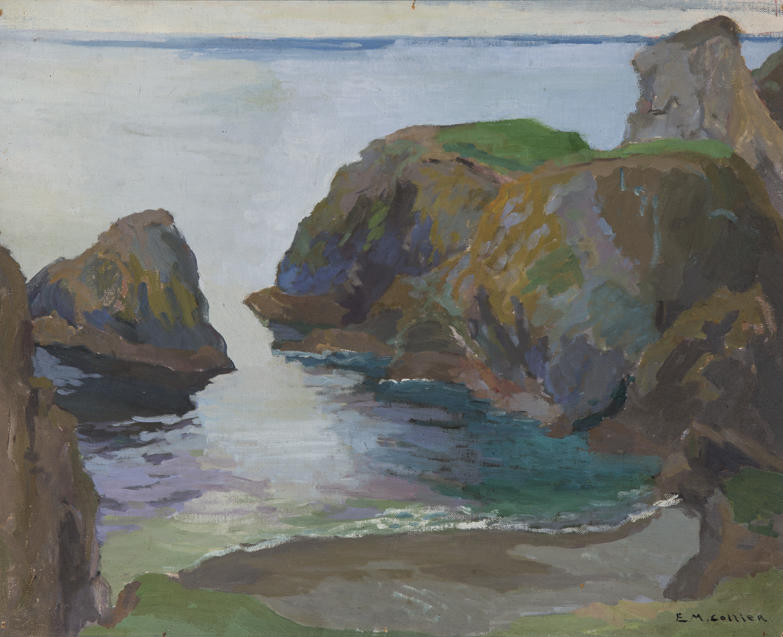

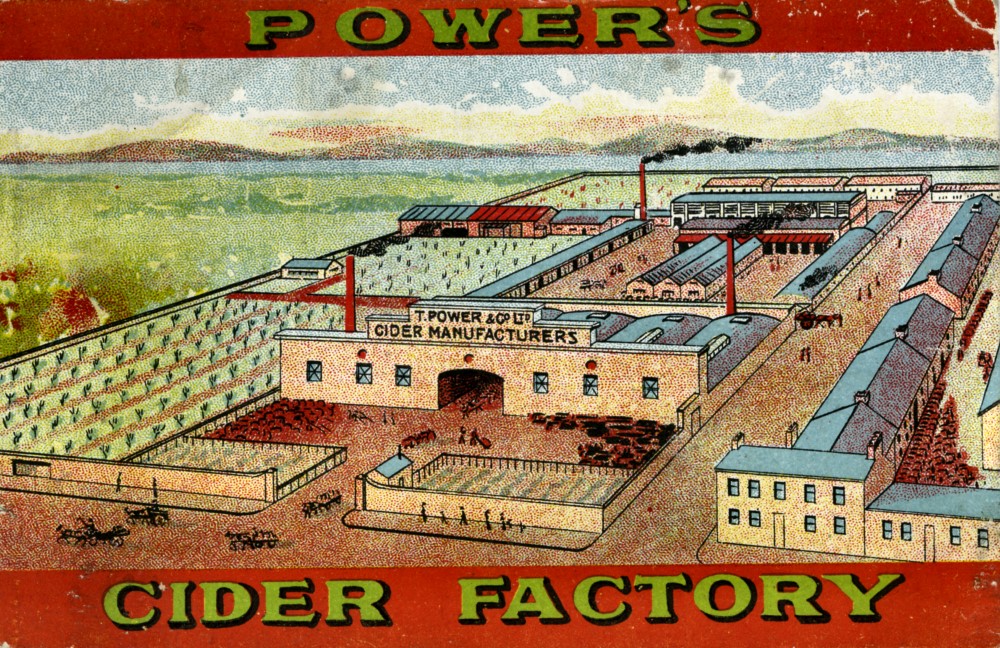

How did this happen? In the terrible natural disasters that afflict Africa, healthy young adults are likely to be the chief survivors. They produce children, and the population gradually recovers. In Ireland, it was the young people who left. Economic change was of course crucial. Growing potatoes had been a labour–intensive activity, and over-dependence upon a single subsistence crop was obviously a bad idea. Irish agriculture shifted towards supplying meat and dairy products for Britain's booming industrial cities. Cattle needed far fewer workers and, as agriculture became mechanised, there was less need for farm labourers anyway. County Waterford, with its mild climate, was in the forefront of change: by 1881, half the county was grassland, with a further one-sixth mountain and scrubland. Waterford City too was simply not big enough to keep up with economic change. The Jacob family were bakers and Quakers who, in 1851, launched a fancy biscuits emporium in the city: it took entrepreneurial panache to take such a gamble in a poor country that was just emerging from Famine. Their initiative was successful – so successful that they soon relocated the business to the larger population centre of Dublin, where in 1916 Jacob's Biscuit Factory would become a stronghold in the Easter Rising. Waterford also lost its shipbuilding industry. The city's shipyards made the mid-century transition from building wooden sailing ships to constructing iron steamboats but, as ocean-going vessels became larger, they could not raise the capital needed for modernisation, and lost out to Belfast. In 1882, the last Waterford shipyard closed – just about the point where the more comfortable and reliable steamships came to dominate the New Zealand route. Across the county, other enterprises had little success. Clashmore's distillery began operations in 1825, but ceased by 1840: its chimney still sits curiously over the village stream. Bunmahon's copper mines ran into trouble in the mid-eighteen sixties and were driven out of business altogether by foreign competition in 1879. An early twentieth-century attempt to reopen them collapsed in 1912, leaving gaunt industrial ruins that attracted a short-lived artists' colony – and Edith Collier, an aspiring painter from Whanganui.

The bustle of the Waterford Quays, captured here in 1910, could not disguise the fact that the city had underperformed economically in the decades since the Famine of the 1840s. But Waterford's maritime links made it easy for local people to emigrate. The Post Office (far left), built in Venetian Gothic style in 1876, was the local communications hub. From the photographic collection of Waterford County Museum.

However, there was something deeper going on, right across Ireland, that drove people to rebuild their lives in distant countries. Essentially, it was the death of hope. There were intermittent phases of modest prosperity – enough for hard-working and ambitious Irish people to save the fare for the journey around the world – but Ireland was dogged by a pervading sense of pessimism. One symptom of this was the decline of the Irish language. In 1881, Waterford was one of three Irish counties where more than half the people could speak Irish. But, in the decades since the Famine, most of them had become bilingual, so that they could switch into a modern, commercial, English-speaking world whenever they needed to. Then, from the eighteen-seventies, families stopped passing on the old language to the next generation, who grew up speaking English only. Put simply and starkly, parents were rearing their children for emigration, ensuring that they could compete effectively in English-speaking countries overseas. An ancient culture was ruthlessly discarded so that its people could make a success of life in New Jersey or New Zealand. A great deal was lost in this astonishing revolution in popular culture: place names ceased to make sense, myths and legends, poems and songs were no longer handed down.

If emigration represents one huge underlying theme in the story of nineteenth- and much of twentieth-century Ireland, it is fair to note that destinations changed over time. In the Hungry 'Forties, people fled the Famine as refugees, seeking the nearest and the cheapest refuges available – many to Britain, others to the United States and some to Canada. (The grandparents of Chicago's notorious Mayor Daley were Famine migrants from Old Parish [An Sean Phobal] in the Waterford Gaeltacht.) But in later decades, the transatlantic torrent was quietly paralleled by a trickle of people to the southern hemisphere. A small but steady number sailed direct for New Zealand. From the eighteen-fifties, the end of convict transportation and discoveries of gold made Australia attractive – and some who travelled there moved on across the Tasman. From 1876, an attempt was made not merely to measure the outflow but to identify the destinations of the people leaving Ireland. Although colonial politicians were trying to woo immigrants, New Zealand was little more than a statistical footnote – the choice of 1,558 travellers in 1876, rising to 3,052 three years later. Spanning people from all 32 counties, it might seem that Waterford could claim only a small share. But in 1880, when numbers dropped back to 1,477, two-thirds of them – 932 in all – hailed from Munster, the south-western counties of Ireland which included Waterford.

References to "the Irish" overwhelmingly assume that the true Irish were members of the Catholic Church. Any outline knowledge of the country's history will note that the Protestant population concentrated in the north-east insisted on remaining within the United Kingdom during the crisis of independence from 1916 to 1922. Across the rest of the country, the Protestant minority is often dismissed as a garrison of privileged landlords and unsympathetic officials, in the twentieth century retrospectively branded as "Anglo-Irish" to hint that they were not the genuine article. In reality, although their surnames usually indicated family origins in England or Scotland, in Victorian times Ireland's Protestants generally regarded themselves as Irish too: indeed, one of their number, Charles Stewart Parnell, was perhaps the country's most effective nationalist leader. Protestants made up around five percent of the population of late-nineteenth century County Waterford, rising to ten percent in the city itself. Most of them were members of the Church of Ireland, the Episcopalian partner of the Anglican Church in England. Although they were generally more prosperous and better educated than their Catholic neighbours, this is not to say that all Protestants were wealthy: indeed, very few owned the property portfolios that their critics claim allowed them to oppress hard-working tenants. In the upper echelons of society, men like Hobson and Triphook were obliged to seek careers in Britain 's armed forces – although, of course, as officers. Many, especially in the city, belonged to an intermediate social tier of skilled workers or shopkeepers, the kind of people who could afford the passage to New Zealand and were no doubt attracted by the colony's Protestant and pro-British culture. But that does not mean that New Zealand's Waterford pioneers all came from the minority community. Further west, migrants from the Blackwater valley were more likely to be Catholics: "when a man emigrates from that side of Waterford he makes for New Zealand or Australia", a Dublin journalist wrote in 1928.

Waterford City and New Zealand The Republic of Ireland's fifth largest city, Waterford has a compact central area in which all the sights (and sites) are within walking distance. The main Kiwi connection is Captain William Hobson, the first British Governor of New Zealand and founder of the city of Auckland, who was born in here on 26 September 1792. He is commemorated by two blue plaques, one high up in the canyon of Lombard Street (probably close to his birthplace), the other – more accessible and interesting – in Patrick Street, at St Patrick's Gateway Centre, the former church where he was baptised. (https://www.waterfordcivictrust.ie/blue-plaques) (The local authority has unfeelingly erected a fine steel pole right in front of the plaque, to display a street sign that might well have been located a few metres away.) Hobson's father, Samuel, was a local barrister. Young William seems to have had a tough childhood, and at the age of 9 (!) was sent away to join the Royal Navy. An elder brother, Richard Hobson, was Dean of the Protestant Cathedral, a handsome eighteenth-century building. Hobson himself apparently subsequently revisited the city to renew family links.

A plaque in Waterford's Patrick Street commemorates William Hobson as the founder of Auckland

William Hobson was sent to New Zealand by the British government to negotiate the Treaty of Waitangi, which was agreed by some – but not all – Māori in February 1840. (It is discussed in more detail in the section that follows, which some readers may wish to skip.) But if "the Treaty" (as New Zealanders informally call it) remains controversial, William Hobson left one enduring mark upon the country that does deserve to be remembered. Once New Zealand became a British colony, Hobson decided that a new capital was required, away from the missionaries at the Bay of Islands which was, in any case, too far to the north. In September 1840, he established a new town on the shores of Waitemata Harbour, a deep-water inlet of the Pacific Ocean. (The local tribe thought a Pākehā town would be a useful asset, and freely sold the necessary land: Hobson resold it as building lots at a handy profit.) When he first went to sea at the age of nine, Hobson had sailed under Captain John Beresford, an illegitimate son (one of many) of the Marquess of Waterford, the local aristocrat who lived at Curraghmore House near Portlaw. However, his career was relaunched in 1834 by the Earl of Auckland, a British politician who had served as Governor-General of India. Hobson named the new settlement after his patron. The capital was moved in 1865 to the more central location of Wellington, but Auckland continued to grow into New Zealand's largest city. Today it is home to 1.65 million people, almost a third of the country's population. Hobson chose well.

There are useful accounts of his life in the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography (https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/1h29/hobson-william) and the Dictionary of Irish Biography (https://www.dib.ie/index.php/biography/hobson-william-a4041).

More about Captain Hobson: why is his Waitangi Treaty so controversial in modern New Zealand? Rapid readers may wish simply to note that both the Treaty of Waitangi and Hobson's interpretation of his appointment were, and are, controversial, and move on to later sections which say more about Waterford links.

In the eighteen-thirties, Māori New Zealand was threatened with destabilisation. The importation of European weapons added new dimensions of slaughter to endemic inter-tribal warfare. Traditional society was also threatened by the arrival of Pākehā, who included some of the toughest elements in European society, whalers and ex-convicts from Australia. In Britain, there were unofficial schemes to send out colonists. There was rivalry between English Protestant and French Catholic missionaries, with the former warning the British government that France was exploiting the priests to gain influence, as they had done in another Polynesian society, Tahiti.

In 1833, James Busby was appointed as British 'Resident' to the Bay of Islands in the northern part of the North Island. Busby was supposed to be a cross between an ambassador and an arbitrator, responsible for keeping the peace between Māori and the Pakeha interlopers. In 1835, he had to deal with Baron Charles Philippe Hippolyte de Thierry, a French exile and eccentric. The Māori chief Hongi Heka had been brought to Cambridge University to help in the publication of a Māori dictionary. De Thierry was a student at the time, and subsequently claimed he had purchased a large area of the North Island from Hongi Heka, who obviously knew a mug when he saw one. De Thierry not only travelled to New Zealand but, on arrival, proclaimed himself its king. In response, Busby persuaded a number of chiefs in the northern part of the North Island to form a European-style state, which he called the Confederation of the United Tribes of New Zealand. The Confederation had its own flag, but nothing much else. With no force to back up his alleged authority, Busby could only plead with the British government for support: Hobson, who was serving in Australia, was sent to investigate. (Through no fault of his own, Busby has generally regarded as a joke figure, but he should be honoured as the founder of the New Zealand wine industry; de Thierry, who was a hilariously silly person, ended his days as a piano teacher in Auckland.)

William Hobson's naval career had been badly timed. By the time he was 22, the long wars against France came to a close: Hobson was a junior officer aboard the convoy that took the fallen Emperor Napoleon to imprisonment on the South Atlantic island of St Helena, the Navy's final flourish. Expenditure on warships was cut back to peacetime levels, and there were few opportunities for promotion. Hobson spent some years in boys'-own adventures fighting pirates in the Mediterranean and the West Indies. On one occasion, he was captured and tortured, an experience which permanently damaged his health. From six years from 1828 to 1834, he had no command at all, and it was during that time that he is thought to have returned to Waterford. Being sent to New Zealand in 1837 was a long-awaited big break.

Hobson wrote a report suggesting negotiations with Māori chiefs to establish a series of bases around the coast. He argued that these would enable Britain to control New Zealand's external trade while contributing, if possible, to the maintenance of order internally. He may have been thinking of medieval Ireland, where towns like Waterford, Cork and Dublin represented bridgeheads of English authority, with the rest of the country left under the chaotic authority of Gaelic chiefs. In reality, as Ireland's unhappy history proved, such half-and-half solutions rarely worked. Once Britain became involved, an all-or-nothing solution was the most likely outcome. By the time British policy-makers sent Hobson back to New Zealand to sort out the problems in 1839, official thinking in London was moving towards outright annexation.

Hence there was ambiguity in Captain Hobson's mission from the start. He was appointed Governor of New Zealand, and instructed to negotiate with the Māori for the transfer of sovereignty over the whole country. In other words, he was declared to be the Governor of a colony that would not exist until he had persuaded the people who lived there to hand it over. Probably this reflected the notion that Captain Cook had claimed New Zealand for Britain when he sailed around the islands in 1769 – but if the country was already British, why have a Treaty at all?

There was also much muddle about the proposed Treaty: with whom was Hobson negotiating? He would obviously have to start with Busby's puppet state, Confederation of the United Tribes of New Zealand, but that had been a failure, and most Māori had never signed up to it anyway. Hence a Treaty would have to be negotiated not only with the nominal Confederation, but with dozens of individual chiefs as well. Did that mean that Hobson would only acquire authority over those areas of New Zealand whose chiefs agreed to accept his authority? The preamble to the Treaty described Hobson as the Governor "of such parts of New Zealand as may be or hereafter shall be ceded to her Majesty", and it also referred to "Her Majesty's Sovereign authority over the whole or any part of those islands". It was all very confusing.

Forty chiefs acceded to the Treaty at Waitangi in the formal conference of 6 February 1840. By the end of the year, there were 500 Māori names attached to the document. But nobody could be entirely sure who had inscribed those names (not surprisingly, Māori were generally illiterate) and what their adherence really meant: for instance, thirteen of the names were women, but only men exercised power in traditional society. And what would become of the areas, especially large regions of the South Island, where nobody had accepted the document?

In practice, Hobson could not allow New Zealand to degenerate into a patchwork of sovereignties. Meanwhile, an unofficial party of settlers from Britain had arrived at what would become Wellington, at the other end of the North Island. In order to assert control over them, in May 1840, Hobson proclaimed the whole of New Zealand to be British territory: the North Island through the Treaty (for which 'signatures' were still being collected) and the South Island by right of Captain Cook's 'discovery'. He was just in time: three months later, a French frigate arrived at Akaroa on the South Island's Banks Peninsula to prepare the way for a shipload of immigrants from France. They found that Hobson had forestalled them by appointing two magistrates to assert British authority.

Obviously, there was a big question mark over the origins of Hobson's claim to rule New Zealand, and it hovers there to this day. Was he the governor because of Captain Cook? Or because the British government had appointed him? Or because some of the Māori had accepted his authority? But what authority had they agreed to accept? Here we come to the murkiest aspect of the Treaty of Waitangi. Incredibly, Hobson, who had no legal training, had been sent out to negotiate a Treaty without any kind of draft document to guide him and no trained lawyers to craft watertight wording. (Compare this with the fraught Downing Street negotiations in December 1921, when the Irish negotiators led by Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith found themselves facing a battery of skilled, experienced and ruthless British politicians who knew how to manipulate the language of the law.) Hobson and Busby, neither of them lawyers, knocked together a document during a week-long conference with Māori leaders, hardly the ideal circumstances to draft a founding charter for a new country.

Worse still, and particularly controversial today, was the challenge of explaining its meaning to the chiefs who were asked to accept it. It was not easy to translate European ideas into the Māori language. Sometimes an existing word could be adapted, but often some new term had to be coined. Thus the Māori word for a chief, "rangatira", could be turned into an abstract concept by adding the suffix –tanga, giving a word that conveyed the notion of sovereignty, "rangatiratanga". But Māori had no notion of administration, day-to-day government, because somehow they managed to exist without civil servants, police or tax-collectors. Their alphabet lacked a hard G and a V, but it was possible to adapt the English word "governor" to "kawana", and extend that to "kawanatanga", to describe the actual process of governance.

Hobson spoke only phrase-book Māori. He and Busby relied upon Henry Williams, a Protestant missionary, who worked against the clock to provide not so much a detailed translation as a general summary. In the English text, Māori conceded "all the rights and powers of sovereignty" over their lands to Queen Victoria ("Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland"). But in the Williams translation, Māori were transferring "te kawanatanga katoa" (complete government) to Wikitoria, " te Kuini o Ingarani [the Queen of England]", which was giving different powers to a different person. There was further confusion when Williams translated his Māori version back into English, providing in effect a rival version of the Treaty. Was this incompetence or a deliberate policy to trick the country's indigenous people?

Henry Williams energetically lobbied Māori leaders to accept British rule, and undoubtedly presented the agreement to them in a favourable light. As the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography says, Williams "must bear some of the responsibility for the failure of the Treaty of Waitangi to provide the basis for peaceful settlement and a lasting understanding between Māori and European". But William Hobson was ultimately responsible for the 'spin' adopted by his enthusiastic agent. There can be little doubt that Māori believed that they had, in effect, out-sourced the preservation of law and order to the British, delegating to the governor authority to control the troublesome Pākehā incomers. They had no idea that they had handed over the sovereignty of their homeland. (Indeed, a recent – and massive – book by Dr Ned Fletcher, The English Text of the Treaty of Waitangi, which is being respectfully discussed in New Zealand, argues that Māori did not concede rangatiratanga at all. If Dr Fletcher's arguments are accepted, this will mean that their original sovereignty must be regarded as in some way fused into the modern-day New Zealand State.)

The Treaty of Waitangi placed New Zealand in an anomalous constitutional position, which for Hobson was made worse by the complication that he lacked adequate force to back up his claim to rule the country. (Unlike poor James Busby, he did have a few troops that he could call upon, but nowhere near enough to intimidate ferocious Māori leaders.) Tāraia Ngākuti was a warlike chief in the Thames district of the North Island. In 1842, he attacked a rival tribe who were Christian converts, demonstrating his contempt for European ways by tossing the heads of two of his victims into a Māori church service. Hobson sent an official to investigate, who quickly abandoned as impracticable his original idea of making an arrest. Pointing out that he had not signed the Treaty of Waitangi and insisting that no Europeans had been involved, Tāraia Ngākuti flatly refused to recognise Hobson's authority. A more worrying problem developed under Hobson's successor, Hōne Heke, one of the most prominent chiefs in the northern part of the North Island, and one of the few who had converted to Christianity. He had urged acceptance of the Treaty of Waitangi, and was the first Māori leader to sign. But he soon became disillusioned with the way British rule intruded upon and undermined traditional Māori society, and in 1845-6 he led an armed resistance. The outbreak of actual fighting was preceded by a famous stand-off, in which Hōne Heke four times chopped down a flagpole flying the Union Jack. Flagpoles have been sensitive symbols in New Zealand ever since. However, William Hobson did not live to see the breakdown of relations with Hōne Heke. Three weeks after the first signing of the Treaty, he had suffered a stroke. A second attack killed him in 1842.

A word is needed on the fate of the Treaty. For a century after its negotiation, Pākehā authorities did not take it seriously. An official of a private colonization company cynically described it as "a praiseworthy device to amuse and pacify savages for the moment". I have seen a parchment copy on display in Wellington: it had been thrown into a store and nibbled by rats. But attitudes gradually changed, and in 1975 the New Zealand established the Waitangi Tribunal to adjudicate Māori claims to traditional rights, in such areas as land-ownership and fishing. The establishment of the Tribunal put the Waitangi Treaty back at the centre of New Zealand life. For at least two generations after the establishment of the Free State, Irish people argued over the legitimacy of "the Treaty" of 1921 as its founding document. In much the same way, New Zealanders today use the same shorthand, still working out how "the Treaty" affects the nature of their country. With the gradual extension of its powers, the Waitangi Tribunal has made a major impact upon New Zealand life. It should be noted that, since 1987, the New Zealand courts have felt free to be guided by the "spirit" of the Treaty, which avoids awkward clashes of wording, and the Tribunal is charged with enforcing its general principles, not necessarily the disputed text itself. This is a reminder that Hobson did try to carry out the instructions he had received in Britain, that he should attempt to create an agreement that would protect Māori from Pakeha incursions. Perhaps he should be remembered in the words that he used (or had memorised) as he shook hands with each of the chiefs at the conclusion of the Treaty ceremony: "He iwi tahi tatou" (We are [now] one people). The Dictionary of New Zealand Biography describes him as "prematurely aged from years in the tropics and from the inroads of disease. His private conduct was irreproachable; he was a good husband, father and friend, a gracious host and an entertaining speaker. … In his official duties he strove to be just, and saw protection of the Māori as a major reason for establishing British rule. He could be obstinate and lacking in diplomacy. He was capable of poor decisions, but the tragedy of his governorship arose mainly from his ill health and inept advisers, and unrealistic Colonial Office [i.e. British government] policy towards the new colony."

Other Waterford City people in New Zealand From the other end of the social spectrum, and the other side of Ireland's religious divide, Patrick Sheridan also played an influential role in settler relations with Māori people, one that has only recently been dragged from the shadows and even now remains obscure. Born in 1841, Sheridan came from Newry in the north of Ireland, but by his teens he was living in Waterford. At the age of fourteen, he qualified as a telegraph operator, which suggests that he was a bright youngster. In 1858, like many an adventurous Irish Catholic lad, he joined the British Army. His unit, the 2nd battalion of the 14th Regiment, was posted to New Zealand, where he arrived in 1860, and took part in fighting against Māori in the Waikato and Taranaki campaigns. He was eventually demobilised in Melbourne, where he married but apparently disliked the city's lawlessness. He returned to New Zealand and took a job in the Native Lands Purchase Office – a government department which purchased Māori land for resale to settlers. He rose through the civil service ranks to become an enormously powerful (but generally invisible) bureaucrat, who was said to know more about Māori affairs than everybody else in the government machine put together. Professor Tom Brooking, the New Zealand historian who has dragged Sheridan partly out of the shadows, reckons that, in effect, he controlled official policy towards New Zealand's indigenous people. One contemporary marvelled that Sheridan often "made Dick or Jock do exactly as he told them". 'Dick' was Richard John Seddon, the colony's Lancashire-born Premier [prime minister], a charismatic publican whose political ascendancy was reflected in his nickname, 'King Dick'. (He turned down a knighthood, fearing that it would be demotion to become merely Sir Richard.) 'Jock' was John McKenzie, a Scottish Highlander who was Minister of Lands and effectively Seddon's deputy. Māori had been forced to surrender large areas of land as a result of the New Zealand Wars, but substantial transfers to government control continued in the following decade. Sheridan, promoted to Chief Land Purchase Officer in 1890, was a key figure here. An admirer wrote that "of all [P]akeha officials he is the most trusted", because Māori liked his "rough diplomacy". It is equally possible to see him as an over-powerful bureaucrat and a bully. He was known as "old Pat" in the corridors of Wellington, but his Māori nickname, "Tamata", is revealing: it means "trying", and suggests that he was relentless in pressurising Māori to hand over their ancestral land. Because he mostly operated behind the scenes, it may never be possible to make a full assessment of Patrick Sheridan's role in New Zealand history, but enough is known to establish that Captain Hobson was not the only Waterford person to play a role in the challenges faced by Māori.

Waterford City also produced some impressive women who helped build a new society on the far side of the world, but the connection got off to an acrimonious start. In the eighteen-seventies, the New Zealand government adopted the bold policy of providing free passages to suitable emigrants from Britain and Ireland. One of the agents employed to recruit the new settlers was Caroline Howard, who had travelled to New Zealand in 1862, chaperoning a party of unmarried young women migrants. She had established an employment agency in Dunedin that helped girls to find work as domestic servants. Following the death of her second husband, she returned to England in 1872. However, her first marriage had ended in divorce – very unusual in those days, and highly scandalous, even when, as in Caroline's case, the wife was the injured party. To the modern mind, she was very well qualified to act as an emigrant agent – but the appointment of a woman to a government post was a startling novelty. By November 1873, she had opened an office in downtown Waterford's King Street (now O'Connell Street), where she publicised "the advantages of New Zealand over any other country for the emigrant, both in nature’s lavish gifts, and for its most genial and health-giving climate". Waterford people were assured that free passages on offer were "a free grant from the New Zealand Government … there is no bond, no tie, no repayment, required". Emigrants were "free to choose both employer and employment on arrival in that colony". Ireland's hard-pressed farm labourers were advised that "a year’s wages would enable them to commence buying good freehold land at a pound an acre. A second year’s wages would stock it, and in ten years they would, by careful industry, be living in comfort and abundance on their own thriving farm, in peace and prosperity, such as they could never hope to attain in a life-time in America". Within a few weeks, she had recruited 350 emigrants. They were sent to London where they were packed into an 869-ton sailing ship, the Woodlark, which sailed in December.

The voyage was an unpleasant experience. The ship was overcrowded and departure arrangements were mildly described as "most confused". Many passengers were "put on board in a miserable state". The Thames was blanketed in thick fog, which added to the confusion of loading supplies. Once the Woodlark had set sail – it took two weeks to limp down the English Channel – "it was found that many necessaries were not on board at all, and that other articles were incomplete". Worse still, one family had been allowed to embark even though they were recovering from scarlet fever – and, indeed, had not shaken it off altogether. Within days, the disease broke out among the passengers: the first fatality occurred on Christmas Eve. In all, there were eighteen deaths, all of them children – although one of the youngsters perished from sunstroke. Even without sickness, the three-month journey was no pleasure cruise. Some of the healthy children seem to have been as much of a menace as the sick ones: a feral minority, curtly dismissed as "cubs", were soon in trouble with the law in their new homeland. When the Woodlark finally arrived in Wellington in mid-March 1874, the nightmare was still not over. With fever aboard, the ship was placed in quarantine, and it would be another fortnight before her passengers were cleared to land. They were treated with suspicion when they did get ashore, and for some months they were blamed for any local outbreaks of disease.

However, it was not so much the physical state of the passengers that became the focus of controversy as their moral character. An official report was scathing, but a careful reading of its condemnation of the Waterford contingent points to prejudice based upon hearsay. "We have learned that some of the worst of the passengers were selected by a Mrs Howard at Waterford, and the conduct, both during the voyage and since their arrival here, of some of the single women, or rather married women who have left their husbands and come out to the Colony as single women, would lead to the inference that they must have been picked up off the streets without any regard to their habits and mode of life. Five minutes' conversation with the captain or surgeon would convince any one that many of these women ought never to have been allowed to come out with other respectable girls who were on board the vessel." The New Zealand historian Professor Charlotte Macdonald has defended Caroline Howard, pointing out that she continued to help women and girls to emigrate until her death in 1907 – by which time she had helped 12,000 of them to make new lives in the southern hemisphere. The disapproving reference to "a Mrs Howard" indicates that she was the prime target, and the stress upon "married women who have left their husbands and come out to the Colony as single women" implied that a divorcee could not be trusted to vet the sexual behaviour of dubious applicants. The "inference" that women had been "picked up off the streets without any regard to their habits" amounted to a thinly-coded but unsubstantiated innuendo that they were prostitutes. No doubt the ship's captain and its surgeon were critical of the failure to exclude passengers who were infectious, and both were probably conditioned by class and gender to disapprove of uppity servant girls, but it was hardly fair to base such generalised character assassination upon an oblique allusion to brief and undocumented comments.

As Professor Macdonald suggests, the denunciation of the Woodlark's Irish passengers also represented a form of dog-whistle sectarianism. The New Zealand government was initially accused of ignoring Ireland in its campaign to recruit new settlers. When it did turn to the Emerald Isle, its efforts seemed to be centred upon Belfast and Derry, the cities in the country's northern Protestant heartland. Caroline Howard's offence was to sign up young women from the other side of Ireland's religious divide: the accusations of sexual immorality represented a covert (if bizarre) way of condemning them for being Irish Catholics. A month after the arrival of the Woodlark, a second party selected by Caroline Howard reached Dunedin – this time mostly composed of workhouse girls from Cork, who were denounced as immoral, ignorant and "certificated scum". Mrs Howard was dismissed, only to be promptly hired to do the same job for the Australian colony of Queensland. The irony behind the denigration of these young Catholic women is that New Zealand did not seek female migrants for their skills at mathematics or their knowledge of foreign languages. They were needed as wives and mothers – in plain language, as bedmates and breeders – and it was inconsistent, if not downright hypocritical, to denounce them for – allegedly – behaving like sexual beings.

One of the "respectable girls" on board the Woodlark was sixteen-year old Mary Crampton (later Player) who had been born in County Kilkenny during the decade that followed the Famine. The handful of Crampton families in Kilkenny had probably originated in England, for most were Protestants who were employed by the landed gentry, but Mary came from a working-class Catholic background: her father was a shoesmith, who made and fitted horseshoes. Kilkenny is part of Waterford's hinterland, and it is likely Mary had come to the city to work as a servant by her mid-teens. She probably qualified for an assisted passage thanks to Caroline Howard's earlier interest in the welfare of domestic servants. Travelling to New Zealand in the nightmare conditions of the Woodlark must have been ordeal for an unaccompanied teenager, but perhaps she was fortunate. A few months later, another emigrant ship, the Cospatrick, caught fire at sea, and 470 lives were lost.

In 1877, Mary Crampton married Edward Player, an English migrant, who tried a range of jobs – storeman, shopkeeper, milkman, sign-writer – but was never very successful at any of them. Over the next twenty years, she did her duty to the colony by producing seven children, one of whom died young. Although New Zealand wanted babies, the colony offered no support for childbirth. Women simply helped one another bring babies into the world and, although it does not seem that she ever acquired formal qualifications, Mary Player became a supportive midwife. This led her into political activity, campaigning for women's refuges and – a short but logical step – supporting the temperance movement, which particularly aimed to stop men from wasting their wages on alcohol.

In keeping with its reputation as the world's experimental social laboratory, in 1893 New Zealand became the first country to allow women to vote. Mary Player wanted to mobilise the new female political lobby into the support of issues vital to women. In 1894, she founded the Women's Social and Political League (WSPL), which demanded improvements in women's legal status and working conditions. Mary herself was particularly concerned for the welfare of domestic servants – a reflection of her own experience as an exploited skivvy. She pressed for government regulation and inspection to protect vulnerable workers, but more radical feminists favoured an alternative strategy of alliance with the male-dominated trade union movement. Far from ushering in a millennium of feminine good sense, the WSPL was soon split into factions. Put simply, Mary Player was a victim of class politics. Most women's rights advocates were middle class, educated, often leisured and programmed to be self-confident. With her working class background and poor schooling, Mary was out-gunned and out-manoeuvred. In 1895, she resigned the presidency of the organisation she had founded, and the rest of her career descended through anticlimax to tragedy. Edward Player died in 1905: he had never been much of a provider, but Mary now became a homeless widow, forced to depend upon her married daughters. In 1924, probably fearing that she had cancer, she took her own life. New Zealand's promoters described the colony as a paradise for working people. Mary Player tried to make that vision into reality. It is her idealism, not her failure, that deserves to be remembered.

Jane Runciman (her friends called her Jeannie) also fought for the rights of New Zealand women in the workplace. Her story starts on The Mall, still the most imposing street in downtown Waterford. Her father, William Runciman, ran a high-class grocery business at numbers 5 and 6, opposite Lombard Street where a plaque recalls the birth New Zealand's first governor, William Hobson. In 1875, two years after Jane's birth, Runciman announced that "in consequence of the rapid increase in his wine trade", he had made "arrangements for direct shipment from the leading growers". Vintages would be imported in wood "and bottled under his immediate supervision, thus enabling him to guarantee their purity and offer special advantages as to quality and price". In addition, his shop would continue to supply teas, coffee, spices "and all the other articles connected with the grocery trade, of best quality and at most moderate prices". It is not difficult to imagine William Runciman's wine barrels being unloaded just around the corner on the Quay, and then carted past Reginald's Tower, the Norman fortress at the heart of the city, to be bottled in his emporium. But the business did not prosper: in 1881, he sought fresh opportunities in New Zealand.

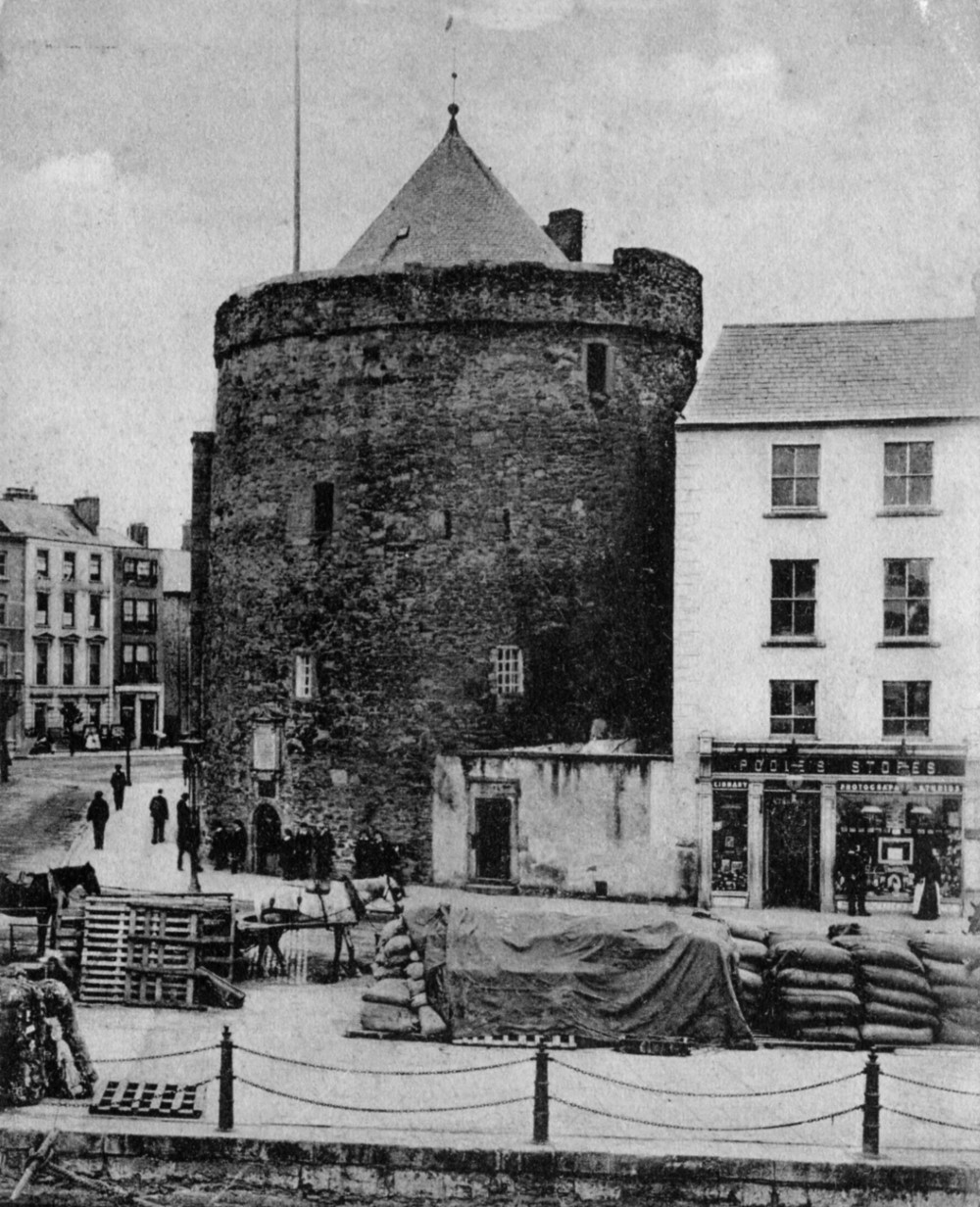

Reginald's Tower, at the junction of the Quays and the Mall (left) is named after a Gaelicised Viking chieftain, Raghnall. It was built by the Normans around 1280, on the site of earlier fortifications. Now part of Waterford's impressive museums complex, it is claimed as Ireland's oldest civic building. It can also be seen as symbolising the beginning of eight centuries of external intervention in Irish affairs. This photograph, from the collection of Waterford County Museum, dates from about 1900, two decades after the Runcimans had left for New Zealand.

What had gone wrong for such an ambitious businessman at such a prestigious location? As already noted, the Waterford City economy was in the doldrums, but Runciman probably supplied the gentry in the surrounding countryside. Between 1879 and 1881, Ireland was convulsed by the Land War. In many places, tenants refused to pay their rents and dared landlords to try to evict them. Many landowners must have been forced to make economies, and their position would become worse when Gladstone's 1881 Land Act created special courts that were empowered to fix rents – and would usually sharply reduce them. William Runciman's upmarket retail enterprise was almost certainly one of the collateral casualties of Parnell's campaign to break landlord power. In 1881, he sailed (as a third-class passenger) on the emigrant ship Hermione to seek opportunities for New Zealand, for the time being leaving the rest of the family in Waterford. For Runciman, being a Protestant was something more than a label for census returns: in New Zealand, the family would be members of the very serious Methodist church. He kept a diary of the 83-day voyage, possibly to let his wife know what awaited her on board ship. It is preserved in the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington, and has been quoted in the Oxford History of New Zealand. Pious emigrants were often shocked by the heathen qualities of their less devout shipmates. Runciman was even more censorious. True, his fellow passengers attended the religious service every Sunday ("the Heavenward Day" as he called it), but they turned out "merely because it is correct to do so not because they have any inward longing for that which is unseen". It was a harsh comment, not least because he could have had no real insight in to the motives of other worshippers, and certainly lacked any right to judge them. Life on board ship was intensely boring: a Sunday service at least broke the monotony, and offered a chance to sing a few hymns. Maybe formal participation might lead to real involvement: who was William Runciman to criticise?

"Susan Runciman and four daughters, including Jane, travelled to New Zealand to join William in Timaru in 1883." That simple sentence in the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography gives a clue to the unsung contribution of so many women to the country's foundation. Jane's mother's maiden name, Susan Propert Williams, suggests that she was Welsh, and hence a newcomer to Waterford. In her early thirties, she was left to supervise William Runciman's business interests in the city: the licence for the premises on The Mall was only transferred to a new dealer in July 1883. It was a huge responsibility for an unaccompanied woman to bring four youngsters half-way around the world. Throughout the long weeks on board ship, it would have been a challenge enough to keep the girls entertained and make some contribution to their schooling, and there was the even more overwhelming issue of safety: a ten-year old had been lost overboard from the Hermione. And all this was a preliminary to the demands of helping her husband to rebuild their lives in New Zealand, where she would go on to have three more children. Women like Susan Runciman may have lacked civic and political rights, but they constituted impressively resourceful role-models for their feminist daughters.

Keen to get back into the retail trade, William Runciman purchased an existing grocery business in the South Island coastal town of Timaru, whose citizens he informed that "from his past experience, and with personal attention to business, he hopes to be able to secure a share of public patronage, as every article will be kept of the best quality, and at the lowest price". But it was a risky venture. The shop's address, in Theodocia Street (named after the daughter of a pioneer settler), was more impressive than the actual location, several blocks from the incipient business district. With barely 4,000 people, Timaru had less than one-fifth of the population of Waterford City. For a couple of years, shipping news in the local press reported the import of packages for Runciman's stores, but it seems that he abandoned the business in 1887. The family moved to Dunedin, where he became an office worker (and would play a walk-on role in the tale of a Waterford fantasist that follows).

No doubt the move to Dunedin enabled William Runciman to support his growing brood, but when Jane left school, there was no question but that she would have to earn her own living. She became a skilled clothing industry technician, serving an apprenticeship to become a "first-class tailoress". However, she was essentially a factory worker. New Zealand had a nascent textile industry, but it operated on tight profit margins. With a population of about 700,000 in the eighteen-nineties, the colony provided a very small domestic market, while hopes of developing an export trade were hampered by the problem that New Zealand was distant from potential customers. Hence factory owners needed to keep wage costs down, and that meant exploiting female labour – for, in that era, there was no prospect of equal pay. When, in 1894, Premier Seddon's reforming ministry imposed a maximum 45-hour working week for women in factories, employers howled in protest. Perhaps it was not surprising that, by 1897, Jane Runciman was drawn into trade union activity. In 1908, she became the general secretary of the New Zealand Federated Tailoresses' Association, and remained a principal organiser of women's trade unionism until her retirement in 1943. She never married.

We may summarise her career by saying that she had to fight on two fronts. Obviously, there were negotiations and occasional confrontations with employers over wages and working conditions. But more surprising was the battle that she had to fight for women's interests inside the male-dominated labour movement. In 1918, she became one of the first women to be elected to the national executive of the New Zealand Labour Party, but it was an uphill task to persuade the men that their fight for decent living standards would be undermined if bosses could draft in cheaper and unorganised female labour. Even when the men accepted the need for them to fight for women's interests, they found it hard to swallow the idea that women should be represented by persons of their own gender. In her home base of Dunedin, the local Labour boss took advantage of her retirement to absorb the women's union into his own organisation. Jane hoped she would live long enough to see her supplanters "come a 'cropper'", but, by the time of her death in 1950, New Zealand's idealistic Labour Party was still several decades from welcoming women MPs, let alone female cabinet ministers.

It is curious that a small provincial city in Ireland should have produced two of New Zealand's feminist pioneers. Jane Runciman spent some time in Wellington in the late 1890s, where she may have met Sarah Player, but New Zealand was still a very regionalised country, and the two women never worked together. If their aims were similar, their tactics were very different: Sarah Player relied upon government intervention to protect vulnerable domestic servants, Jane Runciman urged women factory-workers to fight for their rights.

Arthur Clampett Early In 1889, New Zealand was briefly captivated by a new arrival who called himself Sullivan. Tall, muscular and disdainfully handsome, his Irish-American accent masked the singing voice of an angel. Indeed, he was first noticed when he joined in the hymns at a Methodist gathering. He told a fascinating story, of being born a Catholic and becoming a drunkard before turning his back upon both these forms of error, and feeling himself called to preach to others who were similarly afflicted. Most sensational of all, he claimed not only to have been a prominent athlete in the United States – he had, so he said, once won a swimming race under San Francisco's Golden Gate Bridge – but he also insisted that he was the brother of John L. Sullivan, the world heavyweight boxing champion. For (some, at least) Methodist and Presbyterian clergymen, this made him a very attractive acquisition. Catholics were a definite minority in New Zealand, forming about one-seventh of the population. But the colony's predominantly Protestant culture was stiflingly middle-class and unrelievedly cheerless. A lapsed Catholic who was the brother of the first global sporting megastar could reach out to Irish Catholics and to working men who would otherwise be repelled by the tedious tabernacles of New Zealand Protestantism. First in Auckland and then in Wellington, pulpits were opened to the honeyed oratory of the "converted athlete", and Preacher Sullivan gathered a following of devoted adherents.

Nonetheless, some had their doubts. Mysteriously, his luggage was marked "Clampett", and he was thought also to have used the alias "Santley". For somebody so keen to save souls, he seemed remarkably keen on the comforts of this world. Hospitable churchgoers gave him free accommodation in their homes, prosperous and pious women showered him with money. By the time he headed for the South Island in August, the converted athlete encountered doubters. In Christchurch, the Nonconformist ministers maintained a loose organisation for the discussion of issues of common interest. They invited the newcomer to a meeting to discuss his credentials. He did not appear. "I knew well they would catch me if I went to the convention, and consequently I would not go near it. I thought the parsons would floor me, and I thought I would carry on my game with the view of paralysing them," he later explained. A deputation of ministers called upon him. The encounter was brief and hostile.

At that point, the Coptic docked at Lyttelton, the city's port, and the saga of the glamorous preacher took on a new twist. Travelling on the Coptic was a much more pleasurable experience than the emigration sagas of previous decades. The 4,000-ton steamship made the journey from Plymouth in seven weeks. Not only could it provide more comfortable accommodation than the tiny, storm-tossed sailing vessels, but it was large enough to carry refrigeration equipment for New Zealand's developing trade in the export of frozen meat. Hence there was time for passengers to go ashore while the ship unloaded cargo and took on stores. One of the passengers was a Miss Burns from Waterford, who was on her way to join her sister, who ran a dressmaking business in Wellington. Miss Burns was met by friends – probably also Waterford people – who took her into Christchurch to see the sights. Strolling the downtown streets, she spotted a photograph in a shop window, and was surprised to see familiar face from back home. "Oh!", she exclaimed to her hosts, "there is Arthur Clampett!" The picture was the centrepiece in a display promoting the controversial preacher. With those five words, Miss Burns exploded his impudent imposition.

By the time news of the incident reached the newsroom of the Christchurch Telegraph, the Coptic had sailed for Wellington. Luckily, the Telegraph employed a correspondent in the capital to report parliamentary debates. He received an urgent telegram instructing him to locate Miss Burns and get an interview. Finding her was no problem – her sister's business was located on Lambton Quay, in the centre of Wellington – and the new arrival was happy to chat. "Miss Burns went to school in Waterford, with the members of the Clampett's family, and knew Arthur well. He had sung in the choir of Waterford's Protestant cathedral. She had no idea that he was in New Zealand, but he "was of a roving disposition, and of unsettled habits. ... he is much stouter than when she last saw him some six or seven years ago, but his features are unchanged." This scoop touched off a journalistic feeding frenzy, as editors competed to secure some new angle on the sensational case. A Dunedin newspaper persuaded William Runciman to take part in a virtual identity parade. He was shown a handful of randomly chosen portrait photographs, from which he selected the picture of Clampett. Runciman was "pretty certain" of his identification, "although he would not positively swear to it". He had not seen the man for seven years, but he recognised his characteristic frown. Unfortunately, Clampett's most distinctive feature was his hairstyle, and the preacher was wearing a hat. Like Miss Burns, Runciman remembered Clampett singing in the Protestant cathedral, although he unkindly added that the choirboy had been "without much ear for music".

Clearly, Arthur Clampett was somebody who made an impact on people, although not necessarily for the right reasons. When stories of his New Zealand exploits filtered back to Ireland, a local newspaper published a withering character sketch of a farcical fantasist. "There must be few grown up persons in Waterford who do not well remember Arthur Clampett." His claim to have been a lifelong Catholic was "astounding". In reality, his father had been a shoemaker in Patrick Street who had doubled as the sexton of St Patrick's – the Protestant church associated with Captain Hobson. On leaving school, he had failed to hold down a couple of office jobs, before securing an appointment in the Post Office. (The handsome Post Office, on Custom House Quay, had been built in 1876 in Venetian Gothic style, presumably a statement that Waterford, too, was a great maritime city. It is still in use.) This coincided with his first foray into religious enthusiasm, which led him to irritate his fellow employees by inflicting workplace Bible readings upon them. Dismissed as a disruptive force, he joined the British Army, and appeared in the city as Lieutenant Clampett. It was assume that he had become an officer's batman, and helped himself to the uniform. A soldier could only leave the Army before the conclusion of his term of enlistment by buying himself out: "friends" obligingly rescued him. (Throughout his bizarre odyssey, Clampett could always rely upon gullible dupes to help him evade the consequences of his own follies.) Next, he had perhaps found his true vocation by becoming a cathedral chorister in Tuam, County Galway. The problem was that Tuam has two cathedrals and, in the eyes of his family and friends, Clampett was lifting his voice in the wrong one. Once again, he was rescued, "as his soul was held to be in danger". His voice proving to be a greater asset than his judgement, he joined an opera company in Belfast, where he called himself Signor Clampetti. The market for high culture in the north of Ireland may have been limited for, in the early eighteen-eighties, Arthur Clampett was thought to have headed for America, vanished from Waterford but definitely not forgotten. From across the Tasman came similar derisive warnings about an Australian career – as a "Professor" of swimming – that formed a curtain-raiser to Clampett's starring role in New Zealand. When challenged on this, Clampett claimed that he had accompanied Dion Boucicault, the celebrated Irish actor-playwright, who had toured Australia (incidentally dumping his wife en route).

Although his identification as an imposter led to his being shunned by the respectable clergy of Christchurch, Clampett, still claiming to be Sullivan the Evangelist, continued to make a living through October 1889 by hiring the city's independent Mission Hall and charging his remaining supporters to endure his harangues. (There was a curious irony in this. Christchurch had been founded by a Church of England organisation, which had named the streets after English and Irish bishoprics: the Mission Hall was in Tuam Street.) His admirers proved their devotion by presenting him with £200 and a silver communion set, which he reportedly considered melting down to turn into more cash. But in November, the pressures became too great, and the apostle of temperance fell off the wagon, in a spree that lasted for several days. His bender was the last straw and, to general relief, he was ushered out of town. "His career here has caused intense bitterness, as well as a terrible scandal to the cause of religion." It was generally assumed that he was making his way back to Auckland to take ship for California.

The editor of the Auckland Star decided to try for one last journalistic bite at the Clampett cherry. Two of the paper's ace reporters were tasked with tracking him down and persuading him to confess. It took them several days trap the "unconverted athlete", as his detractors now called him. Clampett shuffled aliases, switched hotels – perhaps to avoid paying his bills – and took refuge in safe houses provided by his few remaining deluded admirers. Vanity was his undoing. The Irish nationalist politician John Dillon was due to arrive in New Zealand, heading a delegation to raise funds in support for the latest challenge to Ireland's landlords. The chance of shaking hands with one of Parnell's principal lieutenants was too much for Clampett's magnetic ego, and he intruded himself into the welcoming party on Auckland's dockside. When one of the scribblers greeted him with an aggressive "Good evening, Mr Santley", Clampett realised that the game was up.

Characteristically, he decided to take charge of the interview, peppering his comments with instructions, such as "Put this down, put it down, it's very important". He confirmed that he was indeed Arthur Clampett, aged 30, from Waterford, but he also asserted that he had been Ireland's national athletic champion, a title that did not exist. He admitted – as he could hardly deny – that he was no relation of John L. Sullivan, although he insisted that he had hung around with the American sporting crowd. (This was probably true: Ned Hanlan, the famous Canadian oarsman, who happened to be in New Zealand, confirmed that he had run across Clampett on the competition circuit.)

Arthur Clampett spoke frankly about the "religious racket", claiming to have made thousands of pounds out of secretly received donations. "The weak-minded women were taken like lambs, and I made money out of their weakness." Widows, it seemed, were a soft touch. When asked how he had equipped himself to be a preacher, he explained that he had "worked up" the New Testament Epistles, the letters attributed to St Paul and addressed to various early churches around the Mediterranean, which were packed with advice and homilies. Thanks to this crash preparation, he "took them all in from left to right". However, it may be that, behind the preacher who took New Zealand by storm – the North Island at least – we may glimpse the choirboy who had sat through cathedral services in Waterford, no doubt imagining himself holding forth in the pulpit. Most clergy of the Church of Ireland were not noted for religious enthusiasm, and some may have possessed a limited repertoire of sacred eloquence. Perhaps they succumbed to the temptation of recycling sermons written for specific festivals, repeating their words from year to year until an adolescent with a retentive memory was word-perfect in their texts. Perhaps, too, resentment at his humble boyhood role explained his continued insistence that he had always been a Catholic – "put that down; it's very important" – and that he intended to die in the faith in which he claimed to have been reared. There was something of the spoilt child in his apparent assumption that a few words of simulated apology would wipe away all his misdemeanours. "I am very sorry if I have offended anybody. Put that down too. ... I am very sorry, and I'll never pick up religion again." It was an odd performance, alternating between the deeply revealing and the utterly fictional. (Clampett would later pretend to have no memory of talking to the Star journalists, claiming that he must have been drunk.) A few days later, he boarded a ship for San Francisco, and New Zealand assumed it had seen the last of Arthur Clampett.

Unfortunately, that comfortable assumption failed to take account of the narcissistic insensitivity of the man himself. Within months, New Zealanders were astonished to learn that Arthur Clampett planned to return. Even more remarkable was the report that a "syndicate" of his supporters in Christchurch had funded his passage. He would later complain that news of his New Zealand exploits had preceded him to the United States, where his friends in the sporting community had turned against him. He had headed for England, where he supported himself by betting on boxing matches and delivered public lectures on the attractions of New Zealand to emigrants, a campaign that the colony's eagle-eyed journalists had somehow failed to report. Speaking, so it claimed, for ninety-nine percent of the population, the Christchurch Star denounced his "impudence". However, far from being Clampett-deniers, the remaining one percent argued that his very fallibility to the demon drink would make his oratory all the more effective in denouncing the slippery slope of alcoholic indulgence. On arriving in Wellington, Clampett issued a statement insisting that his "sole intention" in returning was "to make a public apology in the near future", although there was no suggestion of refunding cash to those he had duped. The Auckland Star had sent one of the reporters who had ambushed him back in December to seek a further interview. Clampett greeted him as an old friend, and explained that he intended to resume his career as "a professor of physical culture", which would include giving "gymnastic exhibitions". Speaking with his habitual "self-possessed deportment", he emphasised that "I am done with the religious racket now."

Unluckily for Clampett, the religious racket had scores to settle. Warned that if he set foot in Christchurch, he would be prosecuted for obtaining money by false pretences, he promptly boarded a ship to Sydney. Clampett was next heard of early in August, on board a steamer from Melbourne to Hobart. The steamship company evidently operated lax security procedures at the dockside, relying upon ticket-collectors on board ship to ensure that passengers had paid their fares. When challenged, Clampett "candidly admitted that he had no ticket", but assured the functionary that his fare would be paid by friends who were meeting him on arrival in Hobart. When these fairy-godparents failed to materialise, he was arrested. Yet again, he was protected by some special Providence, in this case a Hobart publican – a member of a species perhaps not known for philanthropy – who made good the deficiency.

Although he insisted that he had been "drugged and sent to Australia" to prevent him from going on to Christchurch, he remained in Tasmania for several months, giving recitals at musical entertainments around the island, at which he described himself as "the pupil of Signor Gambogie of Milan" – a maestro whose achievements have as yet eluded the internet. By September 1891, he felt it safe to return to New Zealand, where he was soon arrested for an alleged offence of being drunk in public. He protested that the police had found him "in a dying state", having once again been mysteriously drugged. He had also taken "a couple of glasses of brandy" to stimulate the action of his heart, and had assumed that the police had intervened to take him to hospital. (In fact, the Wellington constabulary thoughtfully postponed his court appearance for one week to give him time to sober up.) Clampett's ingenious defence might have been more persuasive had it been supported by medical testimony. In its absence, the magistrate sentenced him to 24 hours' detention unless he paid a fine and met the costs of medical attendance. Yet again, somebody found the cash and Clampett was freed from custody.

Even more remarkably, within weeks, Clampett found a wife. In his notorious Auckland Star interview, he had boasted of "an exceedingly fine girl in New York" whom he planned to marry, but when he finally made it to the altar, his victim was a Christchurch woman, Annie Price. In marriage notices, couples generally supplied their addresses and named their parents. Arthur bombastically listed his notable relatives – not a particularly effective strategy, since the Clampett clan was short on achievement – and described himself as "ex scholar University Medical College, New York City", perhaps to give colour to the self-diagnosis of impending death that he had so recently offered in the Wellington police court. His bride was herself a talented performer, a happy circumstance that would enable her to support herself as a music teacher when Clampett inevitably deserted her, as seems to have happened by the mid-nineties. In 1896, he was in gold-rush Western Australia, where he had reverted to calling himself "Signor Clampetti" and, one detractor put it, "warbles to order in exchange for coin of the realm". In 1901, Annie Clampett, who was teaching in Whanganui, received a telegram from the United States informing her that she was a widow. Her husband, it said, had died of pneumonia at Syracuse in the State of New York. The message added that he had been connected in some way with the town's Military College, which had entitled him to be buried with military honours. The detail is so bizarre that it is tempting to wonder whether Clampett had faked his own death and was embarked on yet another career of fantasy and fraud. However, he was never heard of again. Arthur Clampett most certainly did not represent Waterford most admirable contribution to New Zealand life, but he was undeniably its most amusing.

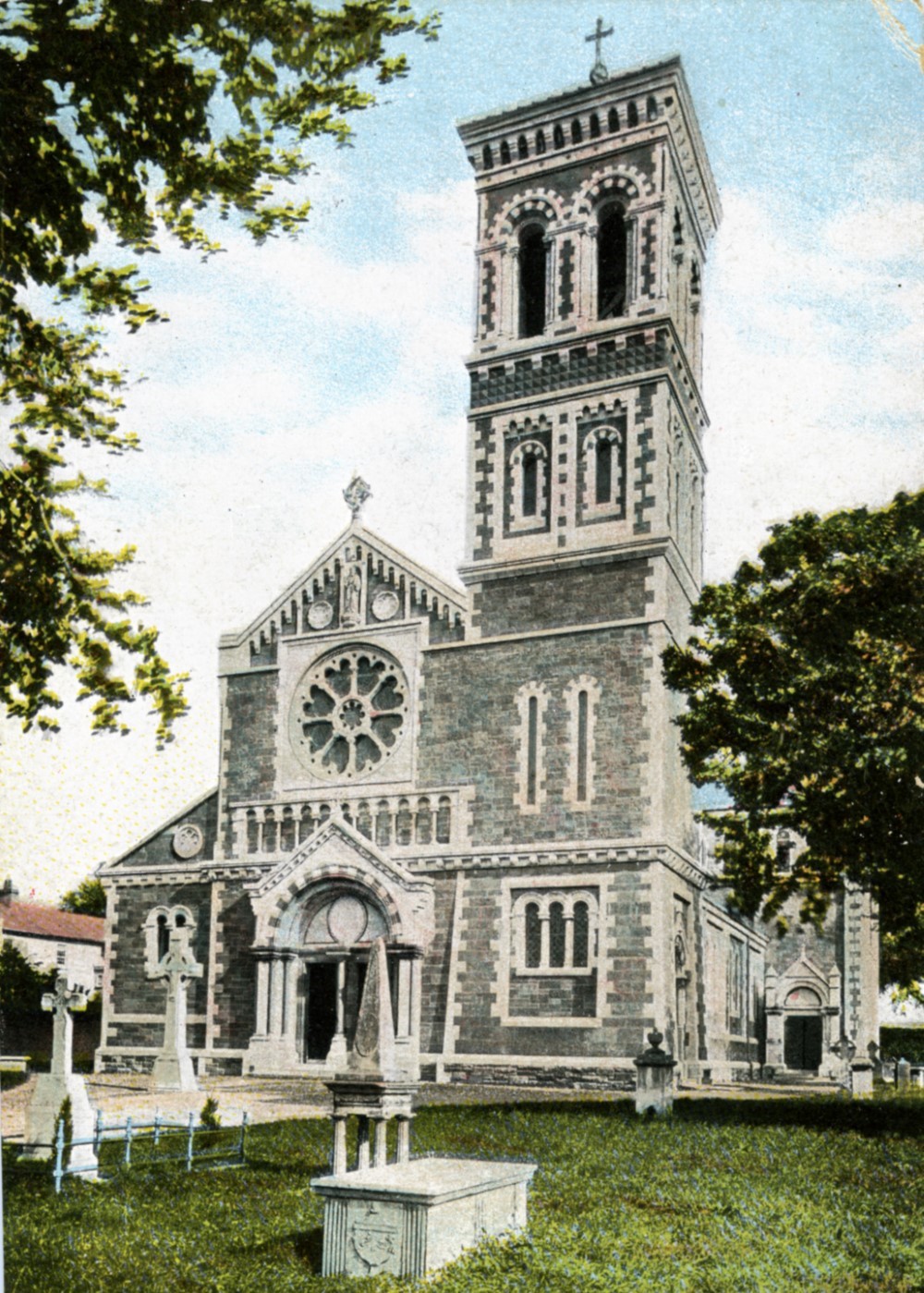

New Zealand's lost Waterford Before leaving the city, we should note that it made a few dents in the map of New Zealand. In 1879, the politician and colonisation promoter George Vesey Stewart laid out a town on Tauranga Harbour, about 35 kilometres north-west of Tauranga itself. It is not known why he decided to call it Waterford. Vesey Stewart came from a gentry background in the north of Ireland, and the parties of settlers that he brought out were mainly from County Tyrone. Possibly the place was named in honour of the family of the Marquess of Waterford, one of whom was invoked by Gilbert and Sullivan, in Patience (1881): "A smack of Lord Waterford, reckless and rollicky." The newcomers largely ignored Vesey Stewart's choice, preferring to use the local Māori name, Katikati. In fact, only the town's post office and the court house were officially called Waterford. The post office switched to Katikati in 1884, according to legend because Vesey Stewart objected that messages had to be addressed to "Waterford New Zealand" to prevent their despatch to Ireland, thereby adding the cost of two extra words to each telegram. In 1897, the local council asked to have the court house renamed too, "there being no such place as Waterford" in the district. There is a Waterford farmstead near Hastings in Hawke's Bay, while a former cattle run of the same name near Christchurch has recently been commemorated by a new subdivision bearing the name at Rakaia.